Introduction [TOP]

The present paper will illustrate current knowledge drawn from sport and performance literature in order to clarify how stressors and perceived level of stress experienced are related to each other. A better understanding of these constructs will hopefully lead to a clearer analysis of the mechanisms around coping responses and coping styles adopted by individuals with ASCs. The objective will be to mark down ways through which resources, support and adaptive changes could assist how stress and anxiety could be dealt with, so optimal performance can be achieved. In some sport and performance literature, stressors have been defined as environmental demands encountered by an individual and have been categorized into three main groups; competitive, organizational and personal stressors (Fletcher, Hanton, & Mellalieu, 2006). These three different groups are explained as follows.

Competitive Stressors [TOP]

Competitive stressors are defined as “an ongoing transaction between an individual and the environmental demands associated primarily and directly with competitive performance” (Fletcher et al., 2006). Therefore, only stressors directly related to competitive performance are named as competitive stressors (for example an opponent strength and qualities in a specific race) (Hanton & Fletcher, 2005). Some other examples include:

-

Preparation for competition (Hanton, Fletcher, & Coughlan, 2005)

-

Competition techniques (Thelwell, Weston, & Greenlees, 2007)

When we consider competitive stressors within the environment for an individual with ASC, it indicates we draw some clear parallels where stressors stemming from the demands placed on the individual with ASC in any environmental account referring to the quality of their performance. Following a simple sequence and/or an adult instruction, that may cause anxiety when the environment is too crowded, noisy or when there is a limited time when the task needs to be completed. Pressure to perform it correctly and efficiently – fear of failure - pressure stemming from having to select relevant information (and skills) for the task, as well as ensuring that all skills necessary – competition techniques – are not only being acquired, but also retrieved at the right moment and eventually mastered. During these times individuals decide to place a significant amount of pressure, and it is important to recognize that potentially undue anxiety on behalf of the individual needs to be better managed and controlled.

Organizational Stressors [TOP]

Organizational stressors are defined as environmental demands which are associated primarily and directly with the organization in which he or she is operating in (Fletcher, Hanton, Mellalieu, & Neil, 2012).

Research in sport literature has proposed a framework of 5 key organizational themes (Fletcher et al., 2006).

-

Factors Intrinsic to sport – Training environment, Travel, Accommodation

-

Roles in Sport Organizations – Role conflict, Ambiguity

-

Organizational Structure & Climate – Cultural and Political Issues

-

Sport Relationships and Interpersonal Demands – Lack of Social Support

-

Athletic Career and Performance development issues – Position insecurity, Career progression.

Understanding organizational stressors within a sporting environment is thought to be significant due to its conflicting nature towards athletic performance and optimal outcomes. Furthermore, contemporary evidence proposes that organizational stressors currently have the most significant influence upon athletic performance (Fletcher et al., 2012).

When translating these types of stressors within organizational environments where individuals on the ASCs have often little control and/or choice over, we can again illustrate how organizational structures, and at times restrictions, can lead to increased levels of anxiety. Factors can include choices on how they travel and with whom, the type of accommodation and/or provision they access, their role within the organization or provision, their social support system (or lack of), their role insecurity, where they are going and aiming in terms of personal aspirations, development and interests. Although empirical evidence in this area is scarce, from professional experience organizational stressors would certainly amount to a significant level of influence and can consequently be considered a potential source of stress upon individuals with ASC, which is often underestimated or at times disregarded altogether. Organizational stressors look very much at the demands of the environment where the individual performs and the dynamics within it. It demonstrates that the physical environment and social environment – people acting, performing within – have significant influence on the performance outcomes of the individual with ASCs.

Personal Stressors [TOP]

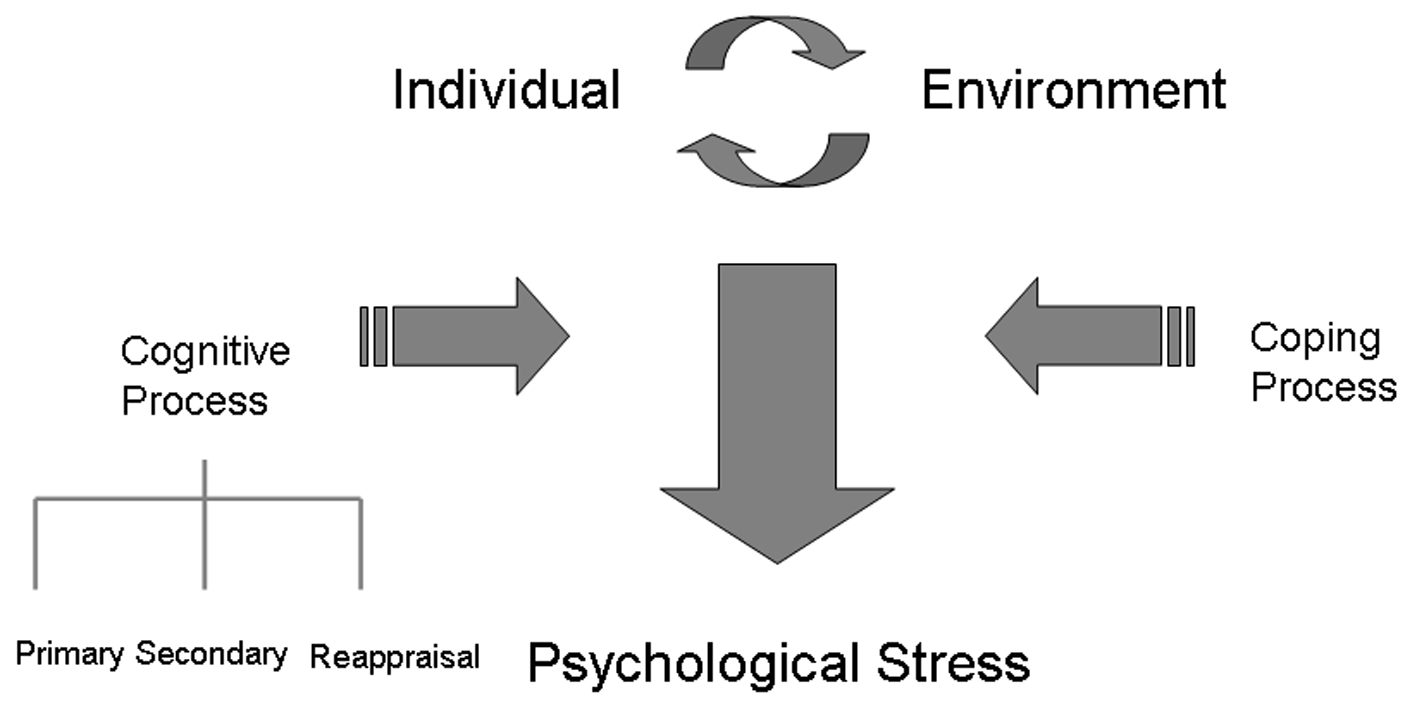

The third classification, personal stressors, is defined as “an ongoing transaction between an individual and the environmental demands associated primarily and directly with personal life events”. Examples can include lifestyle issues and financial issues (Thelwell et al., 2007). Psychological stress reveals a particular relationship between a person and the environment, the way the latter is appraised by the individual as taxing or exceeding one’s own resources as well as endangering one’s own well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). From a theoretical perspective, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) created this transactional model of stress and coping helping to understand the stress appraisal and coping relationship as a process which is fluid and changeable (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Psychological Stress Model adapted from Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, and Novacek (1987) suggested two central processes which determine the outcome of a stressful experience in a given situation: a cognitive and a coping process (see Figure 1). The first includes three basic forms of appraisal: a primary appraisal where the individual assesses the significance of the situation and gauges whether the situation is positive, stressful or irrelevant. A secondary appraisal, which is an assessment of coping resources and options available depending on the situation appraised (e.g. threat, challenge or loss). The third is the notion of reappraisal, which is a state of being ‘on guard’ as processes are in constant motion due to possible changes in the environment and developing coping skills. Emotional reactions need to be mastered and this is when cognitive appraisals leave the stage to different forms of coping processes.

The model asserts that individuals’ cognitive appraisals of potentially stressful situations will be influenced by an interaction between the person (e.g., goals) and the situation (e.g., social interactions, the environment) factors. The transactional model provides a conceptual framework which addresses that stress, rather than a quantifiable and determined entity, needs to be seen as a fluid process which encompasses the overall processes including stressors – the source of the problem issue - appraisals – the way people perceive the issue-strain and coping – the way individuals resolve (or try to resolve), rather than trying to explain it as a single phenomena (Hanton, Fletcher, & Coughlan, 2005). Furthermore, there are changes in our capacity to assess and process stressors as follows.

-

Physiological – Increased Heart Rate, Sweaty Hands, Muscle Tension.

-

Cognitive – Perceptual Changes and Narrowing, Decision Making, Memory, Response Selection.

-

Emotional – Aggression, Frustration, Confusion, Withdrawal from the Situation, Anger.

Physiologically, hormones play a significant part in coping management. The stress hormone cortisol was found to be elevated in males during stressful situations although less so for females. Automatic responses also known as the fight-or-flight responses activate the sympathetic nervous system in the form of an increased focus levels, increased adrenaline production, and epinephrine. When facing threats these responses are activated for survival. These responses are experienced by every one of us with different level of intensity, duration and range, but nonetheless all of us will experience physiological changes. Differences are also felt by the individual perception of the stressor in question and availability and access to personal resources.

For individuals with ASCs this level of anxiety and stress is usually elevated, which makes the process of cognitive appraisal and reappraisal even more taxing. Perceptual narrowing is experienced by difficulties in coordinating movements, seeing and processing perceptual depth (Rodgers, 2000), selecting relevant information for decision making purposes. The ability to self-regulate and recognize signs of stress is also often challenged because of their autism and the challenges associated with their ability to recognize emotional changes in themselves and others.

In the next section, the paper presents current understanding of different coping styles and how these are adopted to address and resolve experienced and perceived levels of stress and anxiety.

Coping: Problem-Focus and Emotion-Focus Coping Styles [TOP]

Coping refers to the individual response to a psychological stressor which is often related to a negative event. However, as illustrated earlier on, stressors can be classified into different areas which do not necessarily amount exclusively to negative events: preparing to go on a trip to the seaside can pose a challenge and potentially raise levels of anxiety and stress in an individual with ASC, despite being considered by most an enjoyable activity. It is therefore the perception of stress levels associated with a specific event/task/activity that will determine how an individual is affected and ultimately how they cope.

People may adopt a range of coping styles though Lazarus and Folkman (1984) have identified two broad categories: problem-focus coping styles and emotion-focus coping styles. People using problem-focus coping styles aim to deal with the source of the problem often tackling and changing it. This can be achieved through finding out more information on the issue and learning new skills to manage it. Problem-focus coping is aimed at changing or eliminating the source of the stress. Folkman and Lazarus (1988) have also identified a further three types within this category: taking control, information seeking, and evaluating negatives and positives within a given situation.

Emotion-focus coping styles instead are aimed towards managing the emotional responses to the perception of a stressful event/situation. Emotion-focus coping styles aim to reduce, alleviate and/or minimise the unpleasant, stressful feeling associated with the stressor. The focus of this coping style is to guide away, accept and/or manage the emotional responses to an unchangeable and/or uncontrollable situation. It is also important to distinguish between an avoidance coping mechanism related to the emotional response coping style and a positive re-appraisal; the latter preferable as a long term emotion-focus coping style mechanism. Distancing or avoiding a situation over an extended period of time can become detrimental to the individual.

A third classification proposed by Carver and Connor-Smith (2010) is identified as the appraisal-focus coping style which aims at challenging the assumption of an individual’s perception of a specific stressor through a cognitive re-evaluation. Our thinking gets challenged and through reappraisal gets re-constructed in a more positive frame. This process is often used in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Beck, 1979). People tend to use a variety of coping styles, according to the stressor and context. However, what seems to be happening in situations when the issue and source of stress continues to negatively affect the person, it is often their inability to adopt the appropriate coping style for a specific situation or lacking the ability to implement cognitive restructuring and a positive re-evaluation for their perceived stressor. Re-framing a situation becomes the key.

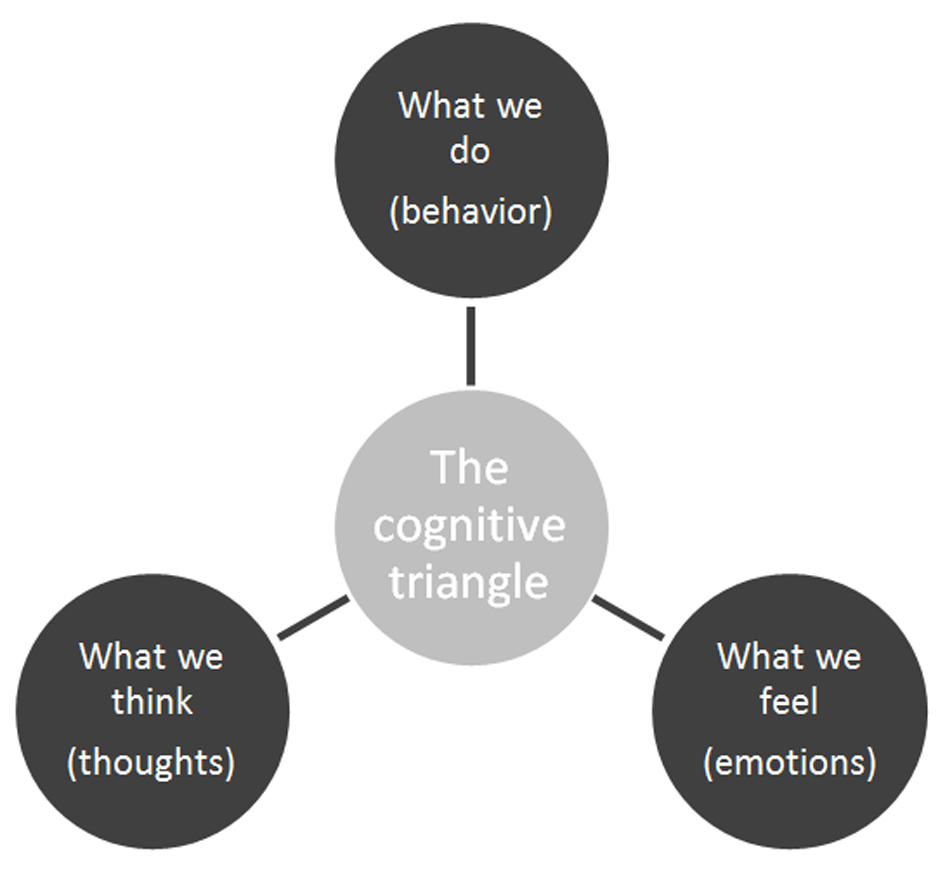

People will tend to adopt problem-focus coping styles for uncontrollable situations whereas they would benefit from adopting an emotion-focus coping style as the situation cannot be changed (or unlikely to be under their control). Conversely, they will tend to adopt emotion-focus coping styles when in reality they could address the situation by acquiring new skills such as for example getting new information, through problem-focus coping styles. Figure 2 below represents what we refer to as the cognitive triangle which aims to explain the interrelationship of how our feelings, thinking (thoughts) and actions (behaviour responses) can affect each others.

One of the challenges experienced by individuals on the ASC, is indeed their ability to adopt these changes, assess and evaluate distressful situations and appraise what can be done as an alternative. Often, they may not necessarily have the ability or skills to perform this mechanism of re-appraisal without significant amount of adult support, visual and gestural prompting and guidance to remain focused, to attend relevant information or filter out irrelevant one. Understanding these mechanisms – behind the source of stress – remains the key if we want to ensure that the most appropriate level of psychological and educational support is provided.

In the next section, the paper aims to illustrate some practical examples on how this process of understanding different sources of stress can lead to a more proactive resolution and adoption of appropriate coping styles rather than relying on reactive responses.

Coping With Competitive Stressors [TOP]

Getting to know the client – this is always the first and most significant step to be adopted for any stress management reduction plan/intervention by being aware and understanding their limitations and more importantly by recognizing and use their strengths. This is the process which would be followed for an elite athlete in order to achieve optimal results in competition. You identify their strengths and work on their weaknesses with a targeted goal-oriented program. The transaction between the individual and their environmental demands related to their performance ought to be considered as a starting point, rather than considering the environment as a static vessel where the individual has to perform – at all costs. Reducing and mitigating stressors means also being able to be tuned in with what the individual with ASC wants to achieve and how they are going to get there. Through clear goal-oriented tasks and activities this can be achieved by using pathways that are appropriate to the individual in terms of skills acquisition, mastery and generalization. There is clear evidence that competition is perceived in the context of people’s environment, therefore such a construct is equally applicable to an elite athlete as much as a person with ASCs.

Coping With Organizational Stressors [TOP]

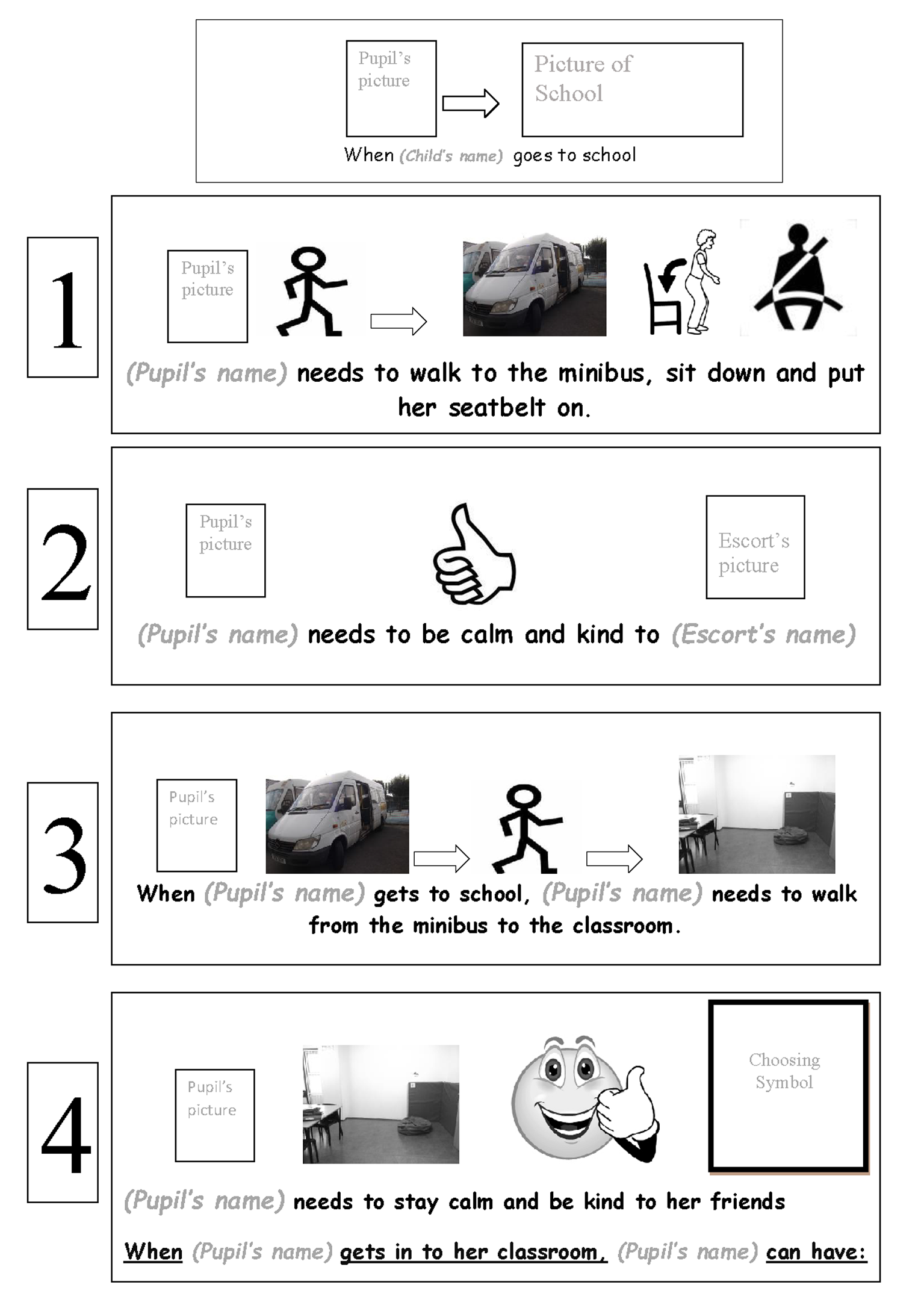

It is important getting to know the client which again remains the most significant step to be adopted when addressing these groups of stressors. In the context of organizational stressors, this will ensure that, as far as possible, and within the constraints of any organization, the client has a voice and can make supported and structured choices within the environment where s/he ‘performs’. This can be achieved through the use of visual schedules (see Figure 3), planning for a change of environment – travel and/or accommodation – which can also be provided through the use of technology, iPads, photo and personalized timetables.

Furthermore, it will be significant to change the environment and organizational structure in order to provide the optimal learning environment. By offering opportunities to the individual in choosing who they will be working with, by looking at their social support and significant others – with who they can build a good-fit and promote positive social interaction, the individual will ultimately increase their participation on where they want to get to and what they want to achieve.

In sport, coach and athlete relationship is one of the most significant factors for competition and performance success (Jowett, 2005). It is about their partnership and overall, this partnership is embedded in the dynamic and complex coaching process and provides the means by which coaches’ and athletes’ needs are expressed and fulfilled (Jowett & Cockerill, 2002). The coach–athlete relationship is recognized as the foundation of coaching and a major force in promoting the development of athletes’ physical and psychosocial skills hence the question: why can we not think of individuals on the ASCs as athletes and professionals supporting them as coaches and how can we get the best out of this partnership?

Coping With Personal Stressors [TOP]

Getting to know the client – having knowledge of the individual with ASCs current personal situation outside the organization – their social support environment, their emotional environment, their communication environment (how and when they communicate) – can help in the process of understanding what other contributing factors amount to the source of stress. This can be achieved through the use of personal pictorial diaries, through gathering and sourcing key information about the individual, what their present situation is like and importantly what their immediate and long-term future is going to be. Who are the significant people in their lives? Carl R. Rogers (1967) explained that a helping relationship involves amongst other things, an ability or desire to understand the other person’s meaning and feelings, demonstrates an interest without being overly emotionally involved, and a sound and growing mutual liking, trust and respect between the two people.

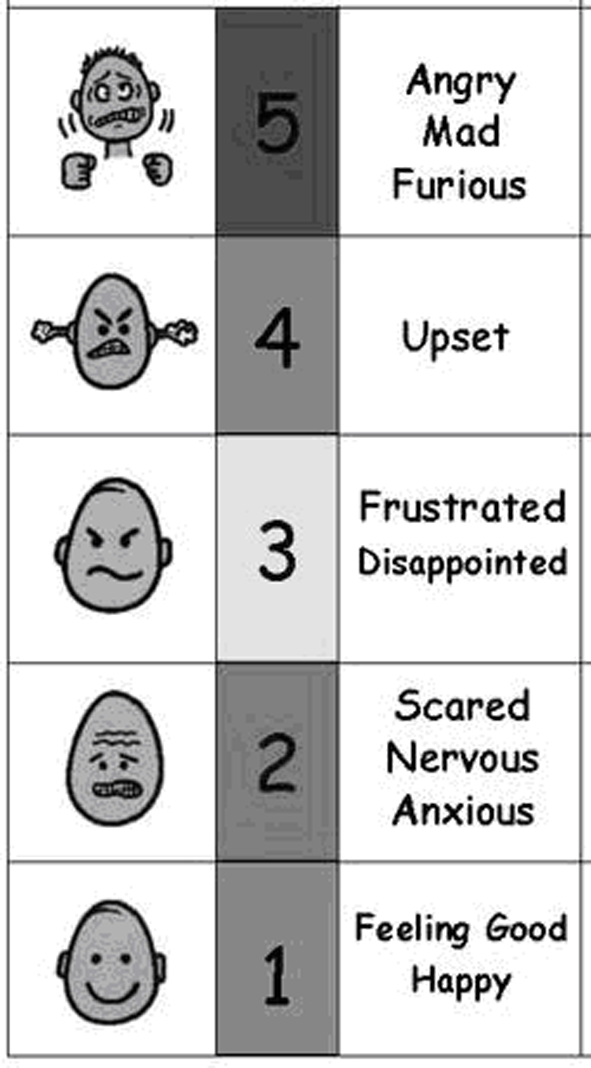

Emotional self-regulation can be taught through the adoption of an emotional-barometer where an individual can be supported in identifying emotional responses to a situation and ways to solve it (See Figure 4). The adoption of breathing exercises, meditation skills can also be introduced and taught.

Summary [TOP]

The aim of this paper was to present a better understanding of coping styles and responses to stressful situations/events in individuals with ASC. By illustrating current knowledge in the sport and performance literature, the paper points out how stressors and stress management is conceptualized and aimed at clarifying the notion of a process which is fluid rather than a static event/situation in time. Sources of stress can be different and perceived differently by each individual. Understanding coping mechanisms and styles behind stress management can help us to better support individuals with ASC there, where skills, resources and access may be scarce. Recently adapted cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) approaches have been used for the benefit of high-functioning individuals with ASC and preliminary results show promising outcomes especially with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Weiss & Lunsky, 2010). Generalisability of CBT has presented a challenge especially for those individuals with ASC who may lack communication and theory of mind skills (the ability to understand what others are experiencing, feeling and thinking). However, MBSR approaches seem to be effective with high functioning adolescents with ASCs through the teaching of meditative breathing skills (Singh et al., 2011).

By exploring current coping styles in individual with ASC and by reflecting on new ways in which level of stress and anxiety can be addressed through acceptance, awareness and observation, noticing what is actually going on, rather than providing a reactive response to the symptoms (both observable and non-observable) will better equip the individual in managing their own stressors. By teaching ways on how to understand and address the relationship between our thoughts and feelings and subsequently our responses/actions to it (behaviors) will support the individual with ASC to better attune to the self and in some ways attune to others. As a result of better understanding how individuals with ASC cope with anxiety induced situations and by providing more sound ways to self-manage such anxieties, they subsequently will benefit from the opportunity perhaps to access a wider range of community-based activities and by bettering the quality of their interactions and experiences.

More empirical studies are needed to ascertain the effectiveness of such approaches and perhaps further knowledge can be again drawn from other fields of sport performance psychology where the mind and body are very much interrelated. The coach-athlete partnership model can also be further explored where the quality and type of constructs – commitment, complementarity, and closeness – could be explored within the client and support staff partnership. How can we optimize the ‘performance’ of individuals with ASCs, how can we ensure that self-management remains at the forefront of priorities for professionals and staff working with them, how can we continue to provide a meaningful and ultimately fulfilling path to their quality of life. These are questions and reflections that remain partly unanswered.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (