Background [TOP]

Public awareness and understanding of psychology in Ghana is far from what psychologists would expect (Oppong, 2011; Oppong, 2013c; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014; Mate-Kole, 2013). For instance, Machungwa (1989, p.55) reports that “Unlike many other physical and social science disciplines, psychology is not well known by the average administrator/policy maker, let alone the average person in [African] countries”. Yet every day, employees and students in Ghana do undergo some forms of testing. Similarly, clinical psychologists at the various psychiatric hospitals or the mental health units in both public and private hospitals perform pre-admission assessment on clients. Psychology training in Ghana is offered in colleges of education for the training of teachers and at the universities. University-level psychology training is offered at three public universities (University of Ghana, University of Cape Coast, and University of Education) and five private universities. The private universities include Methodist University College, Central University, Regent University College of Science and Technology, University of Applied Management-Accra Campus, and Lancaster University-Ghana Campus (Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014).

It is worth noting that only University of Ghana (UG) and University of Cape Coast (UCC) offer psychology training from undergraduate to the doctoral level (Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014). Of the two, it is only UG that offers a PhD in psychology while UCC offers master’s degree in measurement and evaluation and a PhD in curriculum and teaching; again, UCC has commenced offering master’s degree in clinical-health psychology. The Department of Psychology at UG offers a three-credit psychological testing course at the undergraduate, master’s and doctoral levels. The clinical psychology training, provided at both UG and UCC, involves an additional course in psychological assessment. Training in psychological testing at the pre-doctoral level tends to focus on application while the doctoral level training focuses on both application and design of tests. However, courses such as Item Response Theory and Computer-based testing are not offered. As a result, training in such courses will be necessary to build the capacity of psychologists in Ghana. Indeed, psychology is but a growing science in Ghana with much research being done in social, cognitive, clinical, educational, counselling, developmental, and organisational psychology (Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012). The ongoing and past studies, however, tend to employ survey methodology.

One area of application of psychology in Ghana is psychological testing; it is increasingly becoming popular. This is seen in the utilization of psychological tests in not only the traditional domains of education but in non-traditional areas such as employment. For instance, Oppong (2011) reported that with the influx of Nigerian and South African banks into Ghana in the early part of the new millennium, there was the need to screen large numbers of graduates on general cognitive ability. As a result, aptitude testing (or psychometric testing) became popular in Ghana (Oppong, 2011; Oppong, 2013c). Despite this, the validity, reliability and Ghanaian norms for many of these tests are largely unknown and psychological testing is misunderstood by many of the end-users (Oppong, 2011). For instance, an encounter with a managing director (MD) of one of the numerous recruitment agencies by author provided some anecdotal evidence that the said MD understood aptitude tests as tests that looked difficult (Oppong, 2011). Psychological testing is not only applied as a part of the recruitment and selection process but also has other applications in the workplace such as when applied during job analysis, talent management, performance management, employee assistance programmes, customer satisfaction surveys, and employee surveys (Gregory, 2007; Oppong, 2011).

Similarly, testing is inevitable for both the teacher and the student in Ghana’s educational system. Pre-service training of professional teachers exposes them to the principles of test construction, administration, and test scoring (Oduro-Okyireh, 2008). To some extent, professionally trained teachers apply these principles. For example, Oduro-Okyireh (2008), in a study of 265 Mathematics, Integrated Science and English Language (EMS) teachers in 26 Senior Secondary Schools in Ashanti Region of Ghana, reported that:

… [the participating] teachers followed the basic principles in test construction, administration and scoring. Teachers applied seven out of 10 principles in test construction, 12 out of 18 principles in test administration and six out of nine principles in test scoring. Also, teachers reported they used both norm-referenced and criterion-referenced approaches in their test-score interpretation. Again, the findings indicated that pre-service instruction in educational measurement had a positive impact on actual testing practice, although the impact was quite subtle (p. ii).

Similarly, Bello and Tijani (2013), using a sample of 2,422 teachers and 448 heads of schools and educational administrators/officers in Ghana, Nigeria and The Gambia, reported that the participating teachers employed assessment tools like essay tests, objective tests and assignments more frequently. Again, Nabie, Akayuure, and Sofo (2013) also explored the assessment practices of mathematics teachers in Ghana and found that the majority used traditional school assessment tools such as tests, homework and class exercises and followed basic psychological testing principles; this provides some indication that acceptable psychological testing protocols are applied in Ghana’s educational system, though to a limited extent.

There is no attempt to equate psychological testing to testing in mathematics but to emphasize the point that principles of psychological testing are applied in the teacher-made tests used in the school setting. It is also important to note that the educational setting is one of the areas in which psychological testing is applied and that teacher-made tests are achievement tests which are part of measures of maximum performance.

Importantly, psychological testing has also been applied in mental health delivery system in Ghana. For instance, Accra Psychiatric Hospital [APH] (2013) reports that, among other responsibilities, the clinical psychologist at the Department of Clinical Psychology at APH performs the following functions:

-

“assessing a client's needs, abilities or behaviour using a variety of methods, including psychological and neuropsychological tests, interviews and direct observation of behaviour

-

writing assessment report on clients for job or school placement

-

devising and monitoring appropriate programmes of treatment, including therapy, counselling or advice, in collaboration with colleagues”

The involvement of clinical psychologists in mental health delivery has culminated in a situation where psychology graduates are placed at various health centres and clinics to assist the health workers in the provision of psychological services and the deployment of clinical psychologists to the regional hospitals in Ghana (Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014). This programme has been dubbed “PsycCorp”.

However, education, work, and health settings are not the only spheres of life in which psychological knowledge is applied. Training of the personnel of Ghana Police Service, Ghana Armed Forces, Bureau of National Investigation (BNI), the clergy, and social workers involves some application of psychological knowledge. For instance, during the early years of the evolution of psychology in Ghana (or then the Gold Coast), psychology was incorporated into the training of service personnel in education, health, and social and missionary work (or human services) instead of developing as a separate professional or academic discipline (Danquah, 1987; Nsamenang, 2007; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014). Other disciplines such as marketing, occupational health & safety, entrepreneurship, investment finance, risk management, management science, and a host of others have also benefited from psychology; this implies that professionals from these and many other disciplines are engaged in application of psychological knowledge.

However, the current approach to the study and application of psychological knowledge in general and psychological tests in particular has been too Eurocentric and Westernized (Nsamenang, 2007; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Sam, 2014). The current approach largely fails to incorporate cultural contextual factors into its explanations of psychological phenomena. As a result, this limits the applicability of the psychological knowledge to the African setting, and yet, Eurocentric theories are expected to be applied by African psychologists to Africans. Thus, the rest of the paper explores the application of psychological knowledge in Ghana and its associated challenges. On the basis of the problems associated with the general applications of psychology in Ghana, a case is made for Africanising psychology and the development of Pan-African psychology.

Does the challenge associated with application of psychological knowledge in Ghana suggest the “irrelevance” of psychology in Ghana? Despite that the subject matter of modern psychology is culture-bound and culture-blind, Sam (2014) has argued that modern psychology is not useless but failure or refusal to include various perspectives means contributing to human psychology from a limited scope. That psychological tests have issues may not necessarily imply that psychological knowledge have not been applied by other professionals. In its current form, psychological knowledge is still applied by professionals other than psychologists in Ghana (Danquah, 1987; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014). To the extent that application of psychological knowledge occurs in different professions, one can suggest that psychology has far more impact (whether positive or negative) than even psychologists in Ghana have imagined.

Despite the reliance on Western imported tests and the lack of focus on validating tests in Ghana, psychologists, particularly at the Department of Psychology of the University of Ghana have influenced the recruitment and selection processes of a number of state and private organisations. This service has assisted such organisations in screening large pool of job applicants thereby helping them make high quality selection decisions. For instance, national security agencies such as the Ghana Police Service, Ghana Prison Service, Ghana Immigration Service and the Ghana Armed Forces have begun hiring clinical psychologists (Arku, 2010; Ghana Immigration Service, 2012; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012). It is expected that if psychologists enlisted in the security agencies perform effectively, it may have the ripple effect of current employers hiring more psychologists and other security agencies such as Ghana Fire Service also hiring psychologists as well.

Some policy impact of psychology in Ghana includes the development of curricula and national educational policies as well as enactment of the Mental Health Act, 2012 (ACT 846) and the new Health Profession Regulatory Bodies Act, 2013 (ACT 857); these Acts have resulted in the integration of clinical psychology into Ghana’s health service delivery system while ACT 857 establishes Ghana Psychology Council to regulate the training and practice of psychology in Ghana. There also exists Ghana Psychological Association (GPA) as a professional association of Ghanaian psychologists. GPA has instituted an annual psychology research conference as well as co-hosts with the Department of Psychology at UG the “Annual Fiscian-Bulley Memorial Lectures” in honour of Prof. Cyril Edwin Fiscian (1926-2007) and Mr. Herbert Claudius Ayikwei Bulley (1925-2002); the former is considered as the “Initiator” of psychology in Ghana as he commenced the teaching and learning of psychology as an academic discipline in Ghana (Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; A-N. Inusah, personal communication, 25 November 2015). However, Mr. H. C. A. Bulley deserves a special recognition for holding the fort in the wake of the exodus of most Ghanaian psychology lecturers to Nigeria in the 1980s. This exodus hit the psychology department so hard that Bulley had to teach several undergraduate psychology courses, even courses in which he never received advanced education; he, originally, trained as a psychometrician (C. S. Akotia, personal communication, 27 November, 2015). Thus, the Department of Psychology at UG should consider establishing an endowed chair in general psychology in honour of Mr. H. C. Bulley without whose efforts there would not have been a psychology department at the University of Ghana today. Indeed, if Fiscian is regarded as the initiator of psychology for laying the foundation stone, then Bulley rightly deserves to be described as the “Promoter” of psychology in Ghana for building the house.

It is important to note that there are other pioneer psychologists who also deserve similar recognition for their valuable contributions to the establishment of psychology in Ghana, namely: Prof. Samuel A. Danquah, a clinical psychologist, the “father” of behaviour therapy in Ghana; Prof. J. Y. Opoku (1948-2016), a cognitive psychologist; and Dr. Robert Akuamoah-Boateng, an industrial/organizational psychologist and the “father” of industrial psychology in Ghana (Oppong, 2011; Oppong et al., 2014). Additionally, there is the need to also recognize the contributions of Emeritus Prof. Gustav Jahoda towards the establishment of psychology as an academic discipline in Ghana (Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012). In addition to the annual lecture series and its annual conference, GPA also co-hosts the annual mental health conference with Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry of UG.

Towards Africanising Psychology in Ghana and a Pan-African Psychology [TOP]

Despite the general application of psychological knowledge in Ghana since its inception as an academic discipline in 1963 (Agbodeka, 1998), there are still problems associated with such application. Generally, psychological knowledge applied in Africa and Ghana to be specific is still Americo-eurocentric (Mate-Kole, 2013; Nsamenang, 2007; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Peltzer & Bless, 1989). Both Sam (2014) and Berry (2013) have argued that modern psychology in its current form is culture-bound and culture-specific. Berry (2013) further argues that basic psychological processes are common to the Homo sapiens but their development and expression are culturally determined.

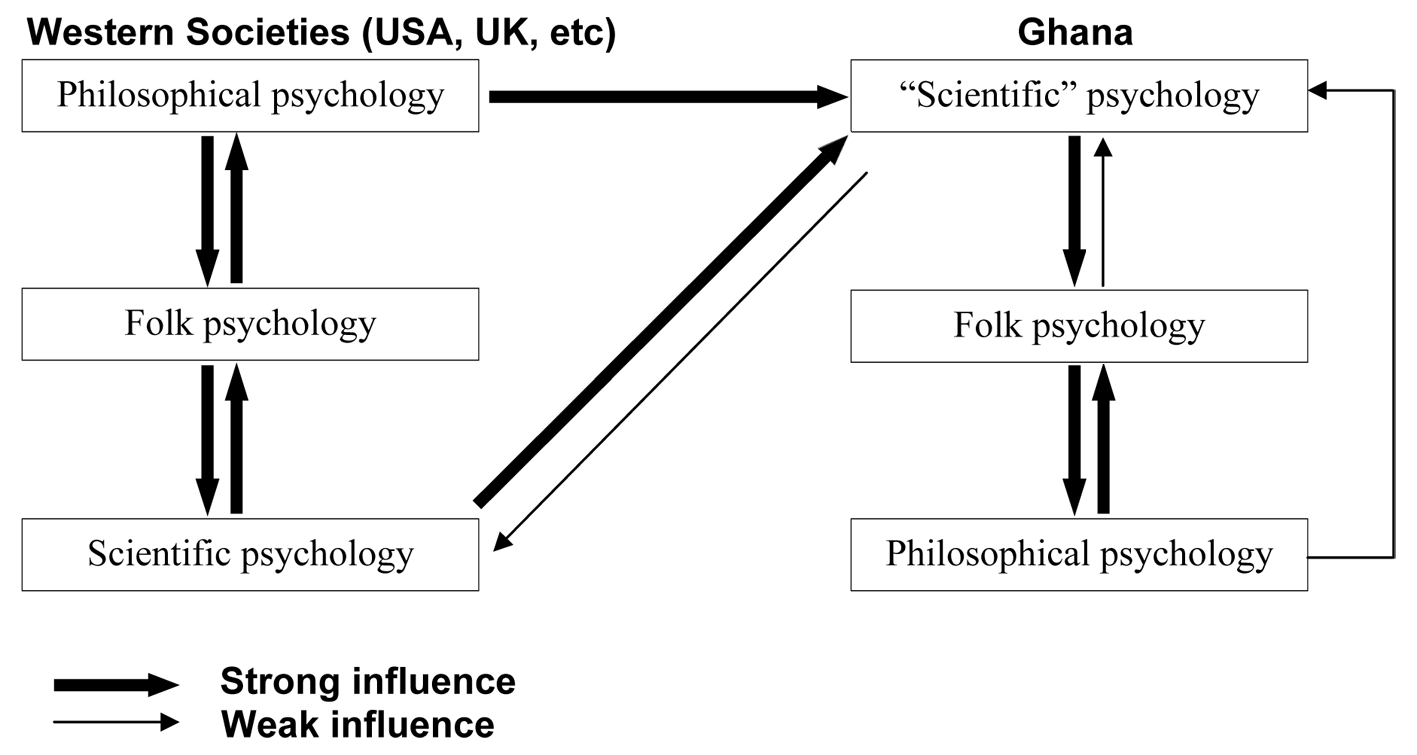

Yang (2012, p. 3) makes a distinction among folk, philosophical, and scientific psychologies. According to him, folk psychology refers to “the ordinary psychological views, assumptions, beliefs, concepts, conjectures, theories, preferences, norms, and practices that have been naturally and gradually acquired through socialization and that are commonly held by the general population of a society” whiles philosophical psychology is “the formal systems of psychological thought as proposed by a society’s philosophers”. He again defined scientific psychology as “a psychological knowledge system constructed by academic or expert psychologists using scientific methodology” (ibidem).

Yang (2012) further makes the argument that current Western or general or mainstream psychology (scientific psychology) is based on both Euro-American folk and philosophical psychologies, making their applications to non-Western societies problematic. Such a view is congruent with the position that “general psychology seeks to discover decontextualized, mechanical, and universal principles and it assumes that current psychological theories are universal” (Koch & Leary, 1985, as cited in Kim, Yang, & Hwang, 2006, p. 3). This suggests that for scientific psychology to be relevant or of benefit to a given society, it must be based on the society’s culture and philosophies. Whiles this can be said about psychology taught and applied in Western societies, such is not the case in non-Western societies as Ghana.

Indeed, Tyson, Jones, and Elcock (2011) have argued that psychology is not an objective, value-free science but rather a reflexive discipline in which there is a constantly evolving interaction between disciplinary psychology and its social context. They argue that “psychologists’ own psychology influences what they do and what kinds of claims they produce” (p. 27) and add that the state, as a significant source of funding and employment, is “able to define roles for psychologists, and dictate the kinds of topics investigated” (p. 29). Thus, he who pays the piper calls the tune. This is even worse for Ghanaian and most African psychologists as the source of funding tends to be external to their state which means that psychological research tend to largely reflect issues of little importance to the social context of the African psychologist. Tyson, Jones, & Elcock (2011) further argue that there are interactions among every psychology of a given socio-historical context, indigenous knowledge, experiential knowledge and expert or disciplinary psychological knowledge. We can, therefore, argue that everyday psychology is deeply embedded in the indigenous knowledge, experiential knowledge and expert knowledge which makes it difficult to have a psychology that is decontextualised and value-free. It is no wonder that the sociology of scientific knowledge literature problematises science in general and critical psychology challenges the erroneous conception of disciplinary psychology as objective and value-free (Teo, 2008; Teo, 2010; Tyson, Jones, & Elcock, 2011). This indicates that the application of psychological knowledge in a different socio-historical context is problematic. This current state of affairs may be conceptualized as in the Figure 1.

Figure 1

Developmental relations among philosophical, folk and scientific psychologies in Ghana and Western societies.

Figure 1 suggests that philosophical psychology is foundational to both folk and scientific psychologies in the Western societies. However, in Ghana, it appears that scientific or Western psychology is being planted on the incompatible Ghanaian “top soil” of folk psychology below which lies the corresponding “deep soil” of philosophical psychology. This view is in consonance with Dr. Amos Wilson’s distinction between the psychology of African people under oppression or psychology of alienation and an African-centered psychology or a psychology of liberation (as cited in Williams, 2008). Indeed, psychology taught and applied in Ghana currently fits the taxonomic category of psychology of alienation. This is because modern psychology is conducted within an absolutist orientation (in which culture is irrelevant) which leads to many ethnocentrically biased conclusions when comparative studies are conducted; this may lead to the rejection of one’s ethnic identity.

Folk psychologies comprise cultural practices, customs, beliefs and values while philosophical psychologies refer to various philosophies espoused in proverbs and ethnic cosmologies have received scholarly attention of eminent Ghanaian philosophers.

In Figure 1, scientific psychology is placed in quotation marks to signify the fact that mainstream psychology as taught and applied in Ghana is not necessarily the same as scientific psychology in the Western societies. Yang (2012) refers to such psychology as Westernized psychology. The current state of affairs in respect of psychology in Ghana has conditioned some students to even reject any discussion about African-centred psychology (Mate-Kole, 2013); this view may even be a true reflection of some psychology teachers. The trivialization of indigenous knowledge systems in the context of imperialistic social science and the denial of epistemological possibilities to non-Western cultures may account for the rejection by the students (Oppong, 2013b; Yankah, 2012). Yankah (2012) points out that the trivialization of indigenous knowledge systems has resulted in the belief that recognized knowledge is one that is articulated in Western languages and educational institutions. Further, Yankah (2012) infers that “his belief has become so strong that people doubt their own wisdom and the wisdom of others if that wisdom has not been articulated in Western educational institutions and languages” (Yankah 2012, p. 52). Indeed, Sekyi (1920, as cited in Asante, 2011) has argued that wherever the European culture reached its deliberately dislocated African institutions including the indigenous knowledge.

It is worthwhile to note that Figure 1 also suggests that both Ghanaian folk and philosophical psychologies exert weak influence on the Westernized body of psychological knowledge being taught and applied in Ghana. Using Kumar’s (2006) classification of published literature into mainstream-validational research and oppositional-indigenous research, many of the published studies in Ghana may be described as mainstream-validational with few exceptions. Again, Westernized psychological knowledge produced, transferred and applied in Ghana also exerts weak influence on Western scientific psychology through cross-cultural psychology as they advance psychology towards a truly global discipline that acknowledges its diversity of ideas and concepts (see Yawson, 2011; Giese & Thiel, 2012; Oppong, Agyemang, & Arkorful, 2013; Owe et al., 2013).

In addition, the Western philosophical psychology continues to exert strong influence on the Westernized psychology in Ghana. This influence occurs through the continued exposure of Ghanaian psychology students to schools of psychology such as structuralism, functionalism, behaviourism, psychodynamics, and a host of others without equal attention to Ghanaian philosophical positions on personhood and causes of behaviour. The recent exposure of doctoral students to philosophy of the social sciences without attention to possible African philosophies further deepens the structural hold of Western philosophies on Ghanaian social scientists in general and psychologists in particular.

Yang (2012) identified six (6) dimensions along which Western psychology differs from Westernized psychology, namely: cultural basis, production method, indigenous autonomy, indigenous contextualization, indigenous compatibility, and indigenous applicability. Indeed, Westernized psychology taught and applied in Ghana has different cultural basis, adopts an imposed-etic approach to research, lacks autonomy (in terms of the indigenously self-directing freedom or independence of a knowledge system among Ghanaian psychologists), has low contextualization (degree to which theories, concepts, methods, and tools have been endogenously developed in the ecological, economic, socio-cultural, and familial contexts existing in Ghana), low compatibility, and low applicability.

Despite the differing cultural origins, psychology in its current form in Ghana has still contributed to national development. As stated earlier, psychology has contributed to developments in health, education and industry. Clinical psychologists have contributed and continue to contribute to the provision of mental health services in Ghana whiles educational psychologists have contributed to the provision of educational services in Ghana. Similarly, industrial/organisational and cognitive psychologists have contributed to the provision of employment testing as well as management of human resources in Corporate Ghana (Asumeng & Opoku, 2014; Oppong, 2011; Oppong, 2013c).

Indigenization is proposed as a significant process for dealing with the lack of cultural fit associated with Ghanaian psychological knowledge. Indeed, it has been suggested by a number of Ghanaian and other African psychologists that indigenizing psychology is key to increasing awareness, ecological validity and applicability of psychology (see Dawes, 1998; Nsamenang, 2007; Oppong, 2011; Oppong, 2013a; Oppong, 2013b; Oppong, 2013c; Oppong, Agyemang & Arkorful, 2013; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Mate-Kole, 2013). In this regard, Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku (2014) have proposed a number of measures that can facilitate the indigenization or domestication project or efforts. These measures include:

-

Carrying out systematic inquiry into psychological practices and techniques that best fit our cultural context using a mixed methods design. The purpose of producing such contextually relevant knowledge is to incorporate such knowledge into the teaching and learning of psychology in Ghana by way of revising existing course content or introducing courses such as Psychology in Ghana or Indigenous Psychology. These courses are expected to be divided into themes that reflect the major applied fields of psychology in Ghana.

-

Drawing on the oral literature (folktales, songs, values, proverbs, maxims, and beliefs) which constitutes the folk and philosophical psychologies of the various ethnic groups in Ghana to develop acceptable psychological theories and models that best explain certain phenomena in their cultural context.

-

Adoption of problem-oriented research paradigms by psychologists as opposed to method-oriented research paradigm. This is to say Ghanaian psychologists should start where other Ghanaian social scientists left off by examining the basic psychological processes underpinning many of the social problems that have been identified and new ones that psychologists can identify. Oppong Asante and Oppong (2012) enumerated a number of such social problems that Ghanaian sociologists have identified.

-

Strengthening of doctoral-level psychology training in Ghana. There is an ongoing effort at restructuring the doctoral training at the University of Ghana, the only public university in Ghana that currently offers doctoral training in psychology. This has resulted in the introduction of one-year course; the new PhD structure is essentially a hybrid one deriving from the North American and Oxbridge doctoral training models.

-

Production of contextually relevant teaching and learning materials; in this vein, the publication of two important readers, Changing Trends in Mental Health Care and Research in Ghana and Contemporary Psychology: Readings from Ghana, has addressed one of the concerns raised by Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku (2014). What is yet to be discovered is the willingness to use these books as teaching and learning materials by Ghanaian academics.

-

Production of domestic journals; this has also been addressed through the publication of Ghana International Journal of Mental Health, Ghana Medical Journal, Ghana Social Science Journal, and the inactive Ghana Journal of Psychology. It is expected that domestic journals would be accorded the same respect as the so-called international journals in terms of being a criterion for promotion and teaching (Addae-Mensah, 2008; Oppong, 2013a; Oppong, 2013b). The failure to accord these domestic journals the needed respect will defeat the purpose of the indigenization project.

In addition to the above-mentioned measures, Ghanaian psychologists are urged to adopt a number of additional measures. As a matter of urgency, we should discourage wholesale rejection of all Western psychological concepts as it is inimical to cross-fertilization of ideas. It is also premature at this stage to make strong suggestion for total rejection of all forms of Eurocentric concepts. To encourage wholesale rejection of Western psychology is to throw away the baby with the dirty water. The responsibility of the Ghanaian and African psychologist will be to attempt to resolve the single most important challenge of modernization that the Ghanaian nationalist Kobina Sekyi (1892-1956) sought to resolve, which is: “how to Westernize without being Westernized; how to preserve while modernizing” (Asante, 2011, p. 96). I shall refer to this challenge as the Sekyi Puzzle of modernity. Our ability to resolve this puzzle will be a major breakthrough in our efforts to Africanise knowledge production in general and psychological science in particular. Indeed, Sekyi (1920, as cited in Asante, 2011, p. 97) argued vehemently in March 1920 at the inauguration of the Gold Coast Chapter of the National Congress of British West Africa, a forerunner of liberation movements in West Africa during days of formal colonization, that:

We cannot expect to get into the way of continuous development while we are following a system of education which depends on the borrowing of an alien physiology, psychology and sociology, a system of education which is based on eschewing by us of the social institutions of our ancestors on the ground merely that our ancestors were uncivilised for just as a condition of health in the individual is health in the society in which he is born, so a condition of self-respect in the individual is reverence for the institutions of his social grouping.

Sekyi’s (1920, as cited in Asante, 2011) argument coupled with Tyson, Jones, & Elcock (2011) contention about the objectivity of psychology suggests that the urgency to Africanise psychological science looms large and the resolution of Sekyi Puzzle of modernity will be indeed chart a course which will be a great departure from current approaches to knowledge production and dissemination in Africa. The resolution of the Sekyi Puzzle represents the next stage of the Africanisation project; this is because it will enable African psychologists resolve the questions about the clashes between Afrocentric and Eurocentric worldviews: must Afrocentric worldview coexist with Eurocentric worldview or should the former replace the latter? This can significantly improve knowledge production in general in Africa which can support socio-economic transformations of African peoples.

Additionally, pedagogy adopted for teaching and learning should condition the Ghanaian psychologist to critically examine Western theories and concepts and not to view them as sacred and beyond critique (Oppong, 2013a; Yang, 2012). At the same time, teachers of psychology should introduce Ghanaian concepts into their teaching either as replacement of Western concepts or supplements to them. For instance, the concept of “Nnoboa” could be used to teach group dynamics. Nnoboa refers to the practice of Ghanaian farmers in which they share labour for cultivation and harvesting without hiring farm workers at a cost. Such pedagogical approaches will benefit from experiences of psychologists in other regions attempting to indigenize the discipline. Thus, Ghanaian psychologists should study and understand the experiences of psychologists in other regions who have succeeded, to a greater degree, in domesticating psychology in their respective countries (Oppong, 2013a; Oppong, 2013b; Oppong, 2013c; Oppong Asante & Oppong, 2012; Oppong, Oppong Asante, & Kumaku, 2014; Yang, 2012) such as Canada, South Africa, Cameroun, India, Brazil and other Latin American countries.

Similarly, the current psychology curriculum implemented in Ghana should be revised to include compulsory courses in African Philosophical Thought, African Psychological Thought: Psychological Implications of Proverbs, Wise-sayings and Ethnic Cosmologies, Parapsychology, History of Ghana, and Sociology or Anthropology of Ghana. These will expose Ghanaian psychology students to the necessary folk and philosophical psychologies required for the indigenization or Africanisation project. Introduction of such courses should encourage Ghanaian psychologists explore Ghanaian ethnic cosmologies to identify and describe their cognitive, affective, and behavioural processes and content in order to elevate folk and philosophical Ghanaian psychologies to indigenous scientific psychology. In this regard, Gavi’s (2009) study of Ananse Modelled Behaviour through folktales or Ananse stories or narratives, Sarfo’s (2010) work on dimensions African Personality, Asante and Akyea’s (2011) study of gender perceptions through the exploration of some Akan and Ewe proverbs are exemplary. Ruto-Korir’s (2006) analysis of Nandi proverbs in his efforts at developing critical psychology in Kenya is very instructive to other African psychologists. Specifically, Ruto-Korir (2006) analyzed Nandi proverbs into psychology of community life and interdependence, psychology of being humane/tolerant/sympathetic, psychology of self-extension, psychology of humility, and psychology of destiny.

Indeed, it is not just a coincidence that the 32nd annual meeting of the US-based Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) was held in Accra, Ghana in 2000 (Williams, 2008) and the first Pan-African Psychology Union (PAPU) workshop was also held in Accra, Ghana in 2013 (Daily Graphic, 2013) while the first psychology reader in Ghana was published in 2014 by a Ghanaian publisher (Akotia & Mate-Kole, 2014). These events constitute significant milestones in the indigenization project. However, in our effort to indigenize psychology in Africa, care must be taken not to produce several ethnic psychologies (as this will produce 54 indigenized psychologies across the continent). Proliferation of ethnic psychologies based on national borders will be self-defeating as these national borders were the inventions of the Western societies in 1885.

Again, cues should be taken from the development of almost single Western psychology despite the different ethnic identities and countries making up the Western world. As a result, the scope of Pan-African psychology needs to be defined. Adapting Padilla’s (2002) definition of Hispanic psychology, Pan-African psychology may be defined as a branch of psychology where the population of interest is persons of African origin, and/or where the target population resides either on the continent of Africa or in the Diaspora. Mazrui’s (2005) distinction between Africans of the soil (including North Africans) and Africans of the blood (including African Americans) is a useful framework for understanding the target population of the Pan-African psychology. The target population of Pan-African psychology may be summarized as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1

Target Population for Pan-African Psychology

| Africans of the Soil | Africans not of the Soil | |

|---|---|---|

| Africans by Blood | (I) Sub-Saharan Africans (Eg: Ghana, Nigeria, South Sudan, etc) |

(II) African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Mulattos |

| Africans not by Blood | (III) North Africans (Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, etc) |

(IV) Africans through adoption, marriage, acquired citizenship, and shared lived experience |

Thus, Pan-African psychology is an indigenous psychology in which both Africans of the soil and by blood are the target population due to their shared history, conditions of living, values, and traditions. These shared attributes include slavery, colonialism, neocolonialism, coloniality, racism, poverty, diseases, damaged self-identity, spirituality, art, communalism, respect for elderly, nature-human harmony, and a host of others. Hence, the objective of all indigenization efforts within the continent and without should be to develop a truly Pan-African psychology.

Among the sub-population, it is those in Quadrant IV (which presents an interesting case. This is because they are neither Africans by blood nor of the soil, a situation which questions the rationale for studying them as part of Pan-African psychology. However, this paper holds the view that their inclusion is key to a comprehensive appreciation of human behaviour within such a discipline. By their association with Africans, such persons take on a new form of personshood that is neither Western nor African. As a result, one cannot administer Western nor African interventions to such persons without appropriate adaptations or modifications.

Pan-African psychology should also adopt a relativist as well as universalist orientations. Sam (2014) defines the relativist orientation as studying human behaviour in its context and in terms of the categories used by the people being studied. Universalist orientation holds that basic human characteristics are common but their display is influenced by culture. It will ensure that country-specific concepts can coexist with Pan-African concepts.

Conclusion [TOP]

This paper sought to determine the degree to which Ghanaians have benefited from psychological knowledge. In carrying out this task, an attempt was made to provide a narrative critical review of state of psychological knowledge and its application in Ghana. Indeed, psychology can be said to have benefitted, to some extent, the Ghanaian in many spheres of life. This is due to the fact that many non-psychologists are exposed to psychological knowledge that they apply in their professional practice knowingly or unknowingly. The paper further examined Ghanaian psychology within the Yang’s (2012) classification of psychology into folk, philosophical, and scientific psychologies. It was shown that despite the application of psychology in Ghana since its inception as an academic discipline in 1963, it has still retained its Western orientation due to the fact that Ghanaian folk and philosophical psychologies have not heavily influenced psychology in Ghana. To this extent, psychology has not been beneficial to the Ghanaian to whom such knowledge has been applied both in testing context and non-testing context. It was suggested that indigenization is key to increasing the benefits that Ghanaians can reap from psychology. In that regard, a number of measures were outlined for the domestication or indigenization of psychology in Ghana. Ghana and Ghanaian psychologists have a role to play in indigenizing psychology on the continent. As a result, African psychologists in general and Ghanaian psychologists in particular should heed to the clarion call to domesticate psychology across the continent to create a Pan-African psychology.

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (