Nowadays, we can state that we live in a flat world (Friedman, 2009) or in a global village (McLuhan & Power, 1989) where multiculturalism and diversity of cultures are a daily reality. Borders are no longer an obstacle on the economic, cultural and linguistic levels (Dusi, Messetti, & Steinbach, 2014). The intercultural contact frequency and the global intercultural interactions, facilitated by the rapid advance of new technologies (e.g., Skype), travelling, an easier access to media and Internet, a global economy, together with expatriation and immigration, make cultural exposure almost inevitable. Cultural exposure can be defined as the experiences that allow individuals to understand and familiarize themselves with different rules, habits, cultural norms and values (Crowne, 2008), through intercultural contacts with individuals from foreign cultures. This intercultural contact and this cultural exposure endow individuals with certain multicultural skills, such as cultural intelligence and multicultural personality, which are considered essential to deal with multiculturalism and cultural diversity, facilitating adjustment and integration into new cultures both in organizational and social contexts (e.g., Earley & Ang, 2003; Earley & Mosakowski, 2004; Leong, 2007; Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000). These skills are a help to adapt to multicultural contexts, promote creativity (e.g., Leung, Maddux, Galinsky, & Chiu, 2008; Liu, Chen, & Yao, 2011; Livermore, 2011), facilitate the conflict management (e.g., Gonçalves, Reis, Sousa, Santos, & Orgambídez-Ramos, 2015), the team management (e.g., Janssens & Brett, 2006), the leadership (e.g., Ng, Van Dyne, & Ang, 2009a) and make the people who have them, more prepare to face the challenges of everyday life, both at professional and social levels. In short, these are competencies with several advantages in various contexts, what makes their study relevant. In addition, they are attributes that are not only more easily developed through intercultural contact (e.g., Crowne, 2008; Livermore, 2011), but they are also influenced by the surrounding environment (e.g., Benet-Martínez & Oishi, 2008), which can either promote or inhibit its growth. So, considering cultural intelligence and multicultural personality as attributes that promote and enhance not only the interaction and effective performance in multicultural contexts, but also equip the individuals with a series of tools that allow them to experience greater satisfaction, better relationship capacity or a greater creativity, it is clearly essential to study its effects as possible predictors of passion for work and satisfaction with life.

Expatriate definitions vary depending on the authors, though its essence is based on the movement of the country of origin to another country. In this study, we assume as expatriates the employees who are sent by their organization to work in one of its foreign branches or subsidiaries (Siers, 2007) to accomplish a job-related goal (Sinangil & Ones, 2003). When their assignment is completed they return to their original country (Foyle, Beer, & Watson, 1998). This assignment can be a short-term international one, defined as a “temporary internal transfer to a foreign subsidiary of between one and twelve months duration” (Collings, Scullion, & Morley, 2007, p. 205) or a long-term international assignment. “Non-expatriates typically work with familiar resources as well as colleagues and external stakeholders and they live in a well-known social context” (Adams, Srivastava, Herriot, & Patterson, 2013, p. 471). So, assuming that the expatriates` cultural exposure is considered an advantage over the non-expatriates, it is our expectation that they exhibit higher levels of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality. On the other hand, considering not only the ease of access to new cultures through new information technologies, but also because organizations have become multicultural spaces, non-expatriates’ are also exposed to multiculturalism. So, non-expatriates are supposed to show different levels of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality, according to their degree of intercultural contact.

Assuming that both society and organizations are now multicultural spaces and that the contact with different cultures is beneficial to the development of the cultural intelligence and multicultural personality, we believe to be relevant, not only to analyze the effect of the degree of intercultural contact on the levels of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality, but also to study the effects of both attributes on variables such as passion for work and satisfaction with life.

In short, a one-factor design study for three degrees of intercultural contact with the following objectives was developed: 1) to compare the cultural intelligence and multicultural personality levels of expatriates and non-expatriates considering the degree of intercultural contact; and 2) to observe the predictive effect of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality on passion for work and life satisfaction.

Literature Review [TOP]

Cultural Intelligence (CQ) [TOP]

In recent years, the ability to adapt to others has been emphasized through the identification of various types of intelligence such as social intelligence, emotional intelligence or interpersonal intelligence (e.g., Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1985; Gardner, 1993; Goleman, 1996). Although cultural intelligence (CQ) is consistent with the Gardner’s (1993) perspectives of intelligence (that focus the adaptability and adjustment to the environment (Gardner, 1993; Sternberg, 2000), it differs from other types of intelligence because it focuses specifically on the culturally diverse interactions (e.g., Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015; Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh, 2008). Earley and Ang (2003), in order to explain why some individuals present a more effective performance than others in multicultural situations, developed a conceptual model of cultural intelligence based on the Sternberg and Detterman’s (1986) multidimensional perspective of intelligence. CQ can then be defined as a set of competencies that facilitate the adaptation to different cultural situations and allow interpret unfamiliar situations and behaviors (Van Dyne, Ang, & Livermore, 2010). Earley and Ang (2003) consider the CQ a multidimensional construct comprising four dimensions: metacognitive, cognitive, motivational and behavioral. The metacognitive dimension refers to cultural awareness and sensitivity during the interaction with different cultures, promoting active thinking about people and situations in unfamiliar environments (Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015). On the other hand, it triggers an analytic thinking about beliefs and habits, and allows individuals to make an assessment and review of the mental maps and thus increasing the understanding capacity (Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh, 2008), i.e., those who are a little off about their own culture are more likely to adopt the habits and customs, and even the non-verbal language of an unfamiliar culture (Earley & Mosakowski, 2004). The cognitive dimension refers to the cultural knowledge of behaviours, practices, norms and beliefs in different cultures, obtained through education, experience and through the media, encompassing knowledge of the social, economic and legal systems of different cultures and values (Rose, Ramalu, Uli, & Kumar, 2010). The motivational dimension conceptualizes the capacity to direct attention and energy towards cultural differences, i.e., it is a form of self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation in intercultural situations (Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh, 2008). The behavioural dimension is one of the most visible dimensions of social interaction and refers to the skill to express, verbally and nonverbally, appropriate behaviours when interacting with people from different cultures (Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh, 2008). It is not enough to show to understand the culture of the host country; you need to prove it through action. The empirical research on CQ is somewhat recent, but the initial results are significant and promising (Earley & Mosakowski, 2004; Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 201556).

Studies in the CQ area have focused their effect on the selection and training of expatriates (Ng, Van Dyne, & Ang, 2009b), expatriates` performance (Ang, Van Dyne, & Koh, 2007; Chen, Lin, & Sawangpattanakul, 2011; Elenkov & Manev, 2009; Lee & Sukoco, 2010) and their adjustment (Ang, Van Dyne, & Koh, 2007), in the global leadership (Ng, Van Dyne, & Ang, 2009a), the socialization of newly arrived immigrants in the host country (Malik, Cooper-Thomas, & Zikic, 2014), the relationship between CQ and personality (Huff, Song, & Gresch, 2014; Şahin, Gurbuz, & Köksal, 2014), the impact of cultural exposure and intercultural contact in increased levels of cultural intelligence (Crowne, 2008) and the influence of intercultural contact and CQ as fundamental to the development of global leaders (Kim & Van Dyne, 2012).

The results of these investigations show the importance of CQ attribute for any individual who is in an unfamiliar culture. Individuals endowed with cultural intelligence are more flexible, more open to change and to the unknown, communicate more easily and are more confident (e.g., Earley & Ang, 2003). It will therefore be expected that this competence is a positive predictor of other behaviors, such as passion for work or satisfaction with life.

Multicultural Personality (MP) [TOP]

Multicultural personality (MP) can be defined as a construct focused on cultural adaptation, intercultural competence, and multicultural effectiveness (Ponterotto, Ruckdeschel, Joseph, Tennenbaum, & Bruno, 2011). Based on the analysis of the set of characteristics pointed out by several authors and previous studies, Van der Zee and Van Oudenhoven (2000) have identified a number of specific personality characteristics, grouping them into five dimensions of multicultural competence. The structure of personality arises from its various dimensions (dispositional factors that continuously determine personality), which are the result of grouping personality traits together (Almiro & Simões, 2010-2011). Multicultural personality differs from other types of personality because these intercultural traits are tailored to face intercultural contexts, denoting specific behavioural predispositions that are predictive of effective adaptation in multicultural environments (Van Erp, Van der Zee, Giebels, & Dujin, 2014). To evaluate these traits, Van der Zee and Van Oudenhoven (2000) developed the multicultural personality questionnaire, since, according to the authors, some investigations point to factors that may be associated with multicultural effectiveness, nevertheless few have developed psychometric instruments to measure these factors (Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015). The multicultural personality questionnaire is more geared to predict the multicultural success than standard personality questionnaires. In general, this questionnaire refers to behavior in multicultural situations. Although the scales of the multicultural personality questionnaire are intrinsically linked with the scales of the Big Five (Barrick & Mount, 1991), they are designed to cover more specific aspects that are crucial to the multicultural success (Van Oudenhoven & Van der Zee, 2002). Thus, this multicultural personality questionnaire was developed to identify specific dispositions of individuals who are associated with different facets of skills (Leong, 2007) and includes 5 dimensions (cultural, open-mindedness, emotional stability, flexibility and social initiative) for measuring the multicultural effectiveness. The cultural empathy dimension, also called sensitivity, is the most mentioned dimension in the cultural effectiveness (Arthur & Bennett, 1995; Ruben, 1976). This dimension refers to the ability to empathize with the feelings, thoughts and behaviours of members from a different cultural group. The open-mindedness refers to an openness and unprejudiced attitude towards different members, norms, and cultural values. The emotional stability dimension relates to the tendency to remain calm in stressful situations vs. a tendency to show strong emotions under stressful circumstances. The fourth dimension is flexibility. Elements of flexibility, such as the ability to learn from mistakes and new experiences, are crucial for multicultural effectiveness (Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015; Spreitzer, McCall, & Mahoney, 1997). The fifth dimension, social initiative, includes an attitude of openness to new cultures, a predisposition to seek and explore new situations, facing them as challenges, and the ability to establish and maintain contacts easily (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000, 2001). These dimensions are positively associated with extroversion, satisfaction with life, work productivity, openness to new experiences, international orientation, social adjustment, job satisfaction, and negatively associated with hostility, neuroticism and social anxiety (e.g., Ali, Van der Zee, & Sanders, 2003; Leong, 2007). According to Van der Zee, Van Oudenhoven, and De Grijs (2004), high results in the five dimensions of MP are successful predictors of complex, little routine and stressful professions, and in tasks that require specific abilities and competences to deal with different types of individuals (Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015).

Most of the studies have identified significant relationships with the multicultural behavior characteristics, and the five dimensions in the aspirations for an international career, the development of multicultural activities, international orientation (Leone, Van der Zee, Van Oudenhoven, Perugini, & Ercolani, 2005) and with the ability to learn foreign languages (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2001).

Assuming that MP appears associated with higher satisfaction levels at work and subjective well-being, it is pertinent to find out its effects on passion for work and satisfaction with life.

The Effect of Intercultural Contact on CQ and MP [TOP]

According to Crowne (2008), cultural exhibition (which allows familiarity with beliefs, norms, and values of a particular culture) can be more superficial (e.g. through travel, reading, watching television programs, studying or contacting someone from another culture) or deeper (e.g., through a process of expatriation or immigration, business traveling, studying and living in another country, through humanitarian missions or military experience). The exposure to a cultural variety allows the individual to improve a better understanding of culture (Chen & Isa, 2003), to learn how to select and apply appropriate behaviors and to adapt them as needed. This situation is supported by the CQ that allows individuals, especially the expatriates, to adjust and adapt more easily to the host country (e.g., Earley & Ang, 2003). Intelligence and personality, despite being stable human characteristics, may evolve or be enriched in some ways, i.e., individuals who tend to maintain contact with different cultures may increase their levels of CQ and MP. Thus, the following hypotheses were formulated:

CQ and MP as Predictors of Passion for Work and Satisfaction With Life [TOP]

Occupying much of the individuals’ time, work is one of the most important parts of life. For some people, work is a way to make money or increasing status, while for others, it is a vocation, it is what gives meaning to their existence, becoming part of their identity (Forest, Mageau, Sarrazin, & Morin, 2011). Passion for work is an individual emotion and a persistent state of desire in a cognitive and emotional evaluative basis for work, which results in consistent intentions and work behaviors, such as being persistent in completing a task, demonstrating organizational citizenship behaviors, or even by taking the initiative to solve work-related problems (Perrewé, Hochwarter, Ferris, Mcallister, & Harris, 2014). Passion for work encourages individuals giving them a sense of accomplishment (Gaan & Mohanty, 2014). Vallerand and Houlfort (2003) defined passion for work as a strong inclination for an activity that an individual likes (or even loves), thinks it is important, and in which invests time and energy on a regular basis. Passion can feed motivation, increase welfare and excite our daily life, but it can also cause negative emotions, lead to obsessive behaviours and interfere with the achievement of a well-adjusted, satisfactory and successful life (Orgambídez-Ramos, Borrego-Alésc, & Gonçalves, 2014). Before this duality between type and intensity of passion, Vallerand and Houlfort (2003) considered a dualistic model of passion: obsessive passion (motivational force that pushes the individual to the activity) and the harmonious passion (motivational force that does not dominate the will of the individual, i.e., it's a personal choice).

Satisfaction with life can be defined as a cognitive judgment of some specific areas of life such as health, work, social relations and autonomy, among others, reflecting the individual well-being, that is, the way and the reasons that lead individuals to live their life in a positive way (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985).

Passion for work and satisfaction with life are variables that may have an added value for individuals and their organizations. Thus it is obvious the importance of identifying their predictors. Investigations have learned the positive aspects of CQ and MP, in the organizational and social contexts, in culturally different environments, or even in a domestic environment (e.g., Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015). They enhance job satisfaction, performance and creativity, promote flexibility, open mind or even trust (e.g., Leung, Maddux, Galinsky, & Chiu, 2008; Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2000, 2001; Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh, 2008; Van Dyne et al., 2012). Moreover, multiculturalism in organizations is now a reality and a challenge, and therefore essential to understand the intercultural complexity, since the organizational culture is strongly influenced by national culture. In sum, if CQ and MP are attributes that not only favour interaction and effective performance in multicultural contexts, but also equip individuals with a series of tools that allow them to experience greater satisfaction, greater openness, cultural empathy, emotional stability, better relationship skills or greater creativity, is then legitimate to expect that CQ and MP promote positive attitudes and behaviors such as passion for work and satisfaction with life. Given the importance of realizing the predictive effect of CQ and MP, the following assumptions were formulated:

H3: Expatriates have higher levels of passion for work and satisfaction with life than non-expatriates.

We believe that this study is relevant, not only because there is a lack of studies addressing the effects of IC on CQ and MP, seeking to establish a comparison between expatriates and non- expatriates with maximum IC and non-expatriates with minimum IC, but also because the identification of passion for work and the satisfaction predictors is central to organizations and their human resources.

Method [TOP]

A one-factor design 3 study (degree of IC: expatriates, non-expatriates with maximum IC and non-expatriates with minimum IC) was carried out. This type of methodology was selected because, although it is not a quasi-experimental study, it has some similarities, such as: the non-random selection of the sample, the possibility of working with comparison groups, and the possibility to analyze several variables simultaneously (e.g., Campbell & Stanley, 2015). No significant differences were found on the three samples (χ2(2, N = 28) = 1.01; p = .603).

Measures [TOP]

Intercultural contact (IC): To assess the independent variable intercultural contact degree, a question was built: "In your day-to-day how often do you contact with people of other nationalities?" evaluated on a scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). To identify participants with maximum and minimum IC, these were grouped into two groups, using the average response for its definition. Thus, individuals who answered between 4 and 7 (regularly, often enough, often and always) in this issue were selected for maximum IC group, and individuals who answered between 1 and 3 (never, rarely, sometimes) for the minimum IC group.

Cultural Intelligence (CQ): The Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS), adapted to the Portuguese population by Sousa, Gonçalves, Reis, and Santos (2015), was originally developed by Van Dyne, Ang, & Koh (2008). It is a multidimensional 20-item measure, rated according to a Likert-type scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), that includes four dimensions of "intelligence": metacognitive (4 items, e.g., Item 2: " I adapt my cultural knowledge when interacting whit people of an unfamiliar culture "), cognitive (6 items, e.g., Item 8: "I know the marriage systems of other cultures "), motivational (5 items, e.g., Item 14: "I appreciate living in unfamiliar cultural backgrounds ") and behavioral (5 items, e.g., Item 20: "I alter my facial expressions when a cross-cultural interaction requires it."). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.95; the alpha of the scale dimensions ranged from 0.88 (Motivational), 0.90 (Cognitive), to 0.93 (Metacognitive and Behavioural) in both samples (expatriates and non-expatriates).

Multicultural Personality (MP): Multicultural personality was assessed through the Portuguese version of the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (reduced version) by Sousa, Gonçalves, Orgambídez-Ramos, and Santos (2015). This instrument was originally developed by Van der Zee and Van Oudenhoven (2000) and consists of 91 items assessing the five dimensions of intercultural competence: cultural empathy (e.g., Item 5: "I try to understand the others’ behaviours"), open-mindedness (e.g., Item 4: "I show interest by other cultures"), social initiative (e.g., Item 1: “I take initiatives"), emotional stability (e.g., Item 7: "I keep calm in tough situations"), and flexibility (e.g., Item 6: "I want to know exactly what is supposed to happen"). Later, Van der Zee, Van Oudenhoven, Ponterotto, and Fietzer (2013) proposed a short version consisting of 40 items. The adaptation to the Portuguese population also resulted in a reduced 40-item version (8 items by dimension), assessed using a Likert 5-point scale (1 – Totally Not Applicable to 5 - Completely Applicable). The Portuguese version of the scale had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91; the alpha for the five dimensions ranged between 0.68 and 0.85. In this study the Cronbach's alpha ranged from 0.70 (flexibility) to 0.81 (Open-Mindedness) in the three samples (expatriates and non-expatriates).

Passion for Work: In this study, we used the adaptation of the Passion Scale to the Portuguese population, by Gonçalves, Orgambídez-Ramos, Ferrão, and Parreira (2014), originally developed by Vallerand and Houlfort (2003). This scale consists of two subscales of 7 items: harmonious passion (e.g., Item 3: "This activity allows me to live memorable experiences"; Item 5: "This activity is in harmony with the other activities in my life") and obsessive passion (e.g. Item 8: "I cannot live without this activity"; Item 13: "I have almost an obsessive feeling for this activity"). This scale can be adapted to any type of activity, assessed according to a Likert 7-point scale (1 - Strongly Disagree to 7 - Strongly Agree). The Cronbach's alpha for the overall scale was 0.87. In this study the Cronbach's alpha was 0.94 in both samples (expatriates and non-expatriates).

Satisfaction with life: We used the adaptation of the SWLS to the Portuguese Population, by Simões (1992), originally developed by Diener et al. (1985). This 5-item tool is rated according to a Likert-type scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) and the results ranging from a minimum of 7 and a maximum of 35, in that the higher is the score, the higher will be the satisfaction with life. In the Portuguese scale adaptation, the reliability coefficient of the scale was 0.77. In the present study the Cronbach's alpha is 0.85 in both samples (expatriates and non-expatriates).

Demographics: In order to characterize the sample, participants were asked to provide basic demographic information, including gender, age, marital status and educational level.

Procedures for the Expatriate Sample [TOP]

Several multinational companies were contacted in order to request the participation of their expatriate employees. Anonymity and confidentiality of responses were guaranteed. The expatriates’ questionnaire was completed via online. No compensation was offered to participants.

Expatriate Sample [TOP]

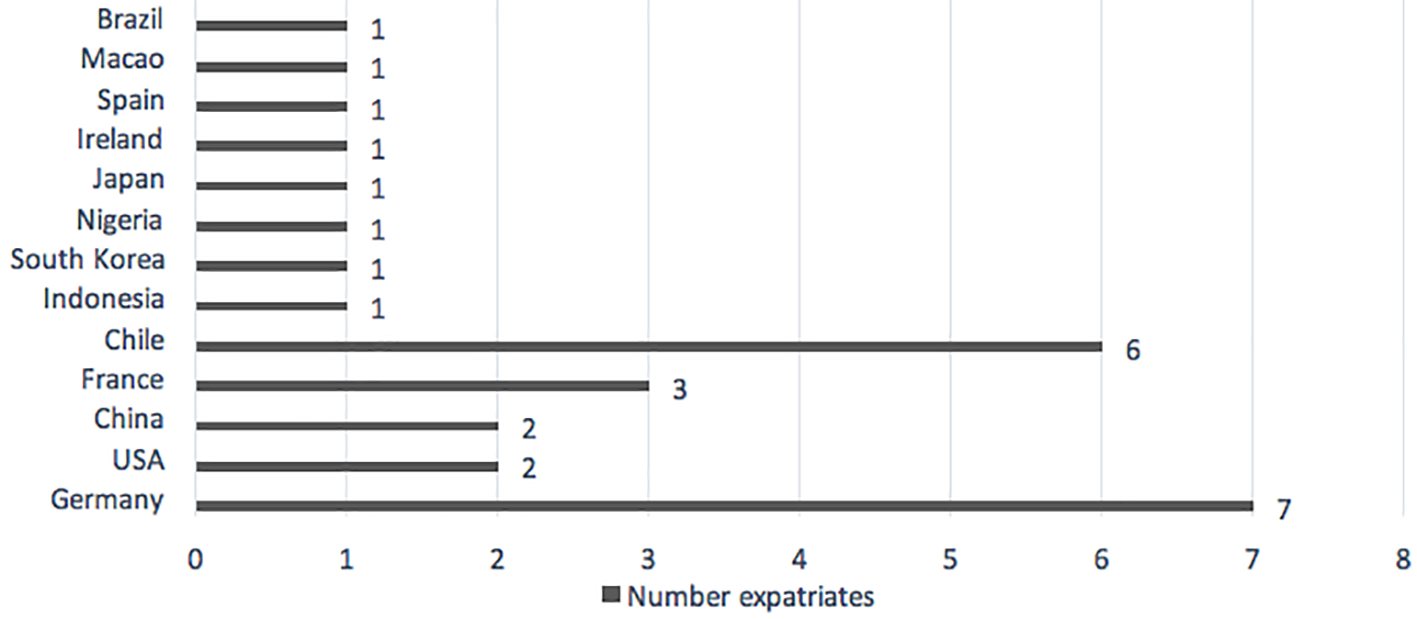

This study used a convenience sample composed of participants who were required to conform to the following inclusion criteria: being expatriate. The sample of expatriates is composed of 28 individuals, and no outliers have been detected. About 71.4% of the participants are males and 28.6% are females, aged between 25 and 66 years (M = 43.61; SD = 10.41). As for nationalities, 24 individuals are of Portuguese nationality and 4 of Brazilian nationality. About 82.1% of the individuals are married or living in common law. With regard to qualifications most of the respondents (39.3%) have a university degree. Half of the respondents (n = 14) are in an expatriation process for the first time. Germany is the country where there are more expatriates, followed by Chile and France (Figure 1). About 20 expatriates are accompanied by their families, 12 of them claim to have always travelled with their family in any expatriation process. Regarding the time period of expatriation, it varies between 1 month and 5 years.

Procedures for the Non-Expatriate Samples [TOP]

Upon approval of the Scientific Committee (entity responsible for monitoring the procedures and ethical safeguards of research) and assurance of ethical criteria (e.g., information about the voluntary and anonymous nature of the study), participants answered a self-report questionnaire with an average completion time of 15 minutes. Data collection was performed in several places, collectively and individually, namely in university classes, public and private companies, public libraries, and other public places. Only the questionnaires completed correctly were considered. No compensation was offered to participants.

As described in measures section: To assess the independent variable intercultural contact degree, a question was built: "In your day-to-day how often do you contact with people of other nationalities?" evaluated on a scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). To identify participants with maximum and minimum IC, these were grouped into two groups, using the average response for its definition. Thus, individuals who answered between 4 and 7 (regularly, often enough, often and always) in this issue were selected for maximum IC group, and individuals who answered between 1 and 3 (never, rarely, sometimes) for the minimum IC group.

Non Expatriates Samples [TOP]

Non-Expatriate Sample (IC Maximum) [TOP]

This study used a convenience sample composed of participants who were required to conform to the following inclusion criteria: age above 18 years. The sample consists of 33 Portuguese participants, 75.8% female and 24.2% male. Ages range from 20 to 72 years (M = 34.79, SD = 13.89). With reference to the level of education, most of the participants have an academic degree (63.6%). No outliers were detected.

Non-Expatriate Sample (IC Medium and Minimum) [TOP]

This study used a convenience sample composed of participants who were required to conform to the following inclusion criteria: age above 18 years. The sample consists of 36 Portuguese participants, 52.8% female and 47.2% male. Ages range from 20 to 74 years (M = 37.18, SD = 14.80). With reference to the level of education most of the participants have an academic degree (66.7%). No outliers were detected.

Data Analysis [TOP]

The data analysis was performed using the SPSS 22 statistical package and it was considered the probability of significance at the level of .05 (Fisher, 1973), since the use of the p value is the most frequently used criterion for a decision on statistical inference (Marôco, 2011). The hypotheses were tested through ANOVA one-way and multiple hierarchical regressions. The homogeneity of variances in the three groups was evaluated with the Levene’s test based on the median, assuming equal variance for p-values above .05. The model assumptions, such as normal distribution, homogeneity and independence of errors, were analyzed. The independence assumption was validated with the Durbin-Watson statistic, which takes values between 0 and 4: values near 2 indicate no autocorrelation of residuals, near 0 indicate a positive autocorrelation, and near 4 indicate a negative autocorrelation (Marôco, 2011). Through Tolerance and VIF measures (Variance Inflation Factor), it was possible to diagnose the existence of multicollinearity. VIF values above 5 (Montgomery & Peck, 1982) or even 10 (Myers, 1986) indicate the presence of multicollinearity in the independent variables, and values closer to 0 denote less multicollinearity. Tolerance varies between 0 and 1, and values closer to 1 reflect less multicollinearity. Tolerance variables with values below 0 are suggested to be excluded from the model (Marôco, 2011).

Results [TOP]

Descriptive Statistic [TOP]

In relation to the IC degree, it can be observed, in the Table 1, the means and standard deviations of the variables under study. We can see that expatriates had higher means in all dimensions except for the cultural empathy dimension (M = 3.70, SD = 0.42). We can also see that non expatriates with maximum IC had higher means in all dimensions except for the flexibility dimension (M = 3.12, SD = 0.38).

Table 1

Means and Standard-Deviations, According to the Level of Intercultural Contact (IC)

| Variable | Expatriates

|

Non-Expatriates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum IC

|

Minimum IC

|

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| CQ | 5.43 | 0.60 | 4.70 | 1.03 | 4.42 | 0.96 |

| CQ Metacognitive | 5.79 | 0.96 | 5.01 | 1.24 | 4.87 | 1.21 |

| CQ Cognitive | 4.77 | 0.85 | 4.14 | 1.10 | 3.83 | 1.13 |

| CQ Motivational | 5.80 | 0.72 | 4.90 | 1.15 | 4.62 | 1.15 |

| CQ Behavioral | 5.56 | 0.97 | 4.93 | 1.38 | 4.56 | 1.28 |

| Cultural Empathy | 3.70 | 0.42 | 3.79 | 0.54 | 3.74 | 0.46 |

| Open-Mindedness | 3.88 | 0.40 | 3.73 | 0.50 | 3.56 | 0.57 |

| Social initiative | 3.99 | 0.44 | 3.73 | 0.67 | 3.50 | 0.42 |

| Emotional Stability | 3.70 | 0.28 | 3.47 | 0.53 | 3.28 | 0.32 |

| Flexibility | 3.32 | 0.46 | 3.12 | 0.38 | 3.27 | 0.42 |

| Work Passion | 4.12 | 0.87 | 3.17 | 0.90 | 2.97 | 1.25 |

| Satisfaction with Life | 5.22 | 0.91 | 4.47 | 1.09 | 4.45 | 0.99 |

To test the Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 it was used an one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey HSD test.

Regarding the MP, significant differences were found in the open-mindedness (F(2,96) = 3.239, p = .04), the social initiative (F(2,96) = 6.539, p = .002) and the emotional stability (F(2,96) = 8.530, p < .001) dimensions. The Tukey test results showed that the main differences were between expatriates and non-expatriates with minimum IC in the open-mindedness (p = .034), the social initiative (p = .001) and the emotional stability (p < .001) dimensions.

With regard to cultural intelligence significant differences were found (p ≤ .001) in all dimensions, differences between expatriates and non-expatriates with maximum IC and between expatriates and non-expatriates with minimum IC. In the behavioral dimension there were only differences between expatriates and non-expatriates with minimum IC (Table 2).

Table 2

ANOVA and Tukey Test for Cultural Intelligence According to the Level of Intercultural Contact

| Variable | ANOVA

|

Tukey Test

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(2,96) | p | Contrast | p | |

| CQ | 10.242 | < .001 | ||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC minimum | < .001 | |||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC maximum | .006 | |||

| CQ Metacognitive | 5.535 | .005 | ||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC minimum | .006 | |||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC maximum | .027 | |||

| CQ Cognitive | 6.407 | .002 | ||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC minimum | .002 | |||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC maximum | .055 | |||

| CQ Motivational | 10.529 | < .001 | ||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC minimum | < .001 | |||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC maximum | .003 | |||

| CQ Behavioral | 5.119 | .008 | ||

| Expatriates vs. non-expatriates IC minimum | .005 | |||

The results also allowed to observe significant differences in the variables passion for work (F(2,96) = 8.974, p <.001) and satisfaction with life (F(2,96) = 5.173, p = .007). Regarding passion for work, these differences can be observed between expatriates and non-expatriates with minimum IC (p = .001) and between expatriates and non-expatriates with maximum IC (p = .007). Similar situation can be observed in satisfaction with life among expatriates and non-expatriates with minimum IC (p = .013) and between expatriates and non-expatriates with maximum IC (p = .019). Given the results we can partially confirm the Hypothesis 1, i.e., expatriates had higher levels of MP and CQ than non-expatriates, except for cultural empathy and flexibility dimensions. Regarding Hypothesis 2, this has not been confirmed. Non-expatriates with maximum IC also presented higher means than non-expatriates with minimum IC (see Table 1), however, the mean difference was not statistically significant. Hypothesis 3 was confirmed; it was found that expatriates had higher levels of passion for work and satisfaction with life compared to non-expatriates.

Regression Analysis [TOP]

To test the 4th hypothesis, we used the multiple linear regression. There were two models for determining the variables in study (CQ and MP) on the passion for work and the satisfaction with life variables (Table 3). The Tolerance and VIF values were found to be close to 1, indicating there was no multicollinearity. The values showed by the Durbin-Watson test were close to 2, indicating no autocorrelation of residuals.

Through Table 3 we can see that the MP explains about 18% of the passion for work. By adding the CQ variable the predictor effect increases about 7% (R2 = 0.25). Only two dimensions have an explanatory power. Cultural empathy contributes negatively to the passion for work (β = -0.322, p = .031) and open mindedness has a positive contribution (β = 0.336, p = .038). We can also verify that the MP explains about 28% of satisfaction with life, and with the adding of the CQ variable this predictor effect increases only 3% (R2 = 0.32). The dimensions with greater explanatory power are social initiative (β = 0.278, p = .028) and emotional stability (β = 0.242, p = .036). These numbers, although small, they are statistically significant (p ≤ .05), confirming Hypothesis 4, i.e., MP and CQ are predictors of passion for work and satisfaction with life.

Discussion [TOP]

This study aimed to compare the expatriates and non-expatriates` CQ and MP levels regarding the independent variable: degree of intercultural contact, as well as to observe the predictor effect of CQ and MP in passion for work and satisfaction with life. The results obtained reinforce the Hypothesis 1, verifying that individuals in expatriation processes had higher levels of CQ and MP compared to non-expatriate individuals. As mentioned above, expatriates had greater cultural exposure as they were supposed to live, even for a limited time period, in a foreign country. This grants them a daily contact with the host country natives and their habits, customs and values, what facilitates the assimilation of their culture. Some studies have shown that IC can act as a source of security decreasing the negative reactions before the unknown (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001), since it reduces prejudices and anxiety and increases empathy (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Other studies have pointed out that a positive IC also appears associated with the development of CQ and MP (e.g., Crowne, 2008) functioning as an adjustment facilitator as it gives an emotional support (e.g., Geeraert, Demoulin, & Demes, 2014). Thus, it seems clear that expatriates presented higher levels of CQ and MP than non-expatriates.

It was also observed that the CQ and MP means of non-expatriates with maximum IC were reasonable. Such evidence showed that even without leaving their home country, individuals who come into contact with people from other cultures can acquire these multicultural competencies. Therefore, the IC came as a predictor of CQ and MP. Although expatriates with maximum IC presented superior means than non-expatriates with minimum IC, these means were not significant and therefore did not confirm Hypothesis 2. It was also possible to confirm the Hypothesis 3, by registering that expatriates had higher levels of passion for work and satisfaction with life. This evidence is consistent with our Hypothesis 4, that is, CQ and MP are predictors of satisfaction with life and passion for work. By allowing a better adjustment to different cultural environments, CQ and MP equip individuals with the necessary tools to deal with situations such as culture shock, stress or anxiety. Thus, individuals experience greater well-being, an easier adjustment and adaptation, what gives them greater satisfaction with life and greater passion for their work.

Conclusion [TOP]

This study confirmed that the IC associated with multicultural competencies such as CQ and MP are extremely important variables for adaptation and adjustment to different and unfamiliar cultures. Even individuals who are not expatriates but who maintain a high IC, have high CQ and MP levels, what confirms that IC is a strong predictor of multicultural competencies. So, individuals who have international experience and maintain a frequent IC will probably be individuals with a greater willingness to adjust to foreign countries, also showing higher levels of CQ and MP. This international experience together with IC should be considered by organizations, for example in recruitment and selection of expatriates, seeking to mitigate the premature returns and aiming the success of international missions, which represent a challenge for expatriates. As the adjustment of expatriates is one of the most critical factors in achieving international missions, organizations must invest in the development or improvement of adjustment practices that focus on IC. The IC allows people to develop a better understanding of the culture, and like the CQ it allows them to select, adjust and use the right competences to each situation.

This study is also a contribution to the definition of validity measures predictive of the expatriate selection processes and to intervention strategies in the expatriate training area. Research-action studies may be developed, using assessment centers extended to host country participants to evaluate to what extent IC contributes to the effectiveness of integration strategies. It would also be interesting to analyze to what extent the levels of CQ and MP vary according to the cultural values (Sousa, Gonçalves, & Cunha, 2015). In this study, the sample was homogeneous with respect to the nationality (Portuguese and Brazilian). Portugal and Brazil are countries historically marked by multiculturalism. Therefore, it seems natural that individuals demonstrate acceptable levels of CQ and MP, a certain openness and cultural empathy. What are the levels of CQ and MP of individuals from countries more closed to multiculturalism and to the world (e.g., North Korea)? And what are their effect on passion for work and satisfaction with life? What is the importance of culture in these two multicultural competencies?

Despite the IC be inevitable for expatriates, some may sometimes have a reduced IC because they are "confined" to expatriate communities of the same nationality, and only interact the strictly necessary with members of the host country. Are their levels of CQ and MP as high as expatriates who are out of communities? Future studies could cover such expatriates, to compare their levels of CQ and MP and verify the impact of the IC.

Regarding the CQ, Van Dyne et al. (2012) built more specific sub-dimensions that allow for a more sophisticated theorizing and testing, adding eleven sub dimensions to the first four dimensions. Therefore, it would be appropriate to deepen various relevant CQ profiles, covering the various sub dimensions recently proposed by the authors (Van Dyne et al., 2012). It would also be relevant to deepen the different CQ profiles, encompassing the various sub dimensions recently proposed by the authors (Van Dyne et al., 2012). With an increasing focus on positive psychology and on the optimal functioning of individuals, the development of attitudes, emotions and positive behaviors such as passion for work and satisfaction with life, is becoming a pressing challenge for organizations.

As limitations we can point out the sample size, the large age diapason and the lack of control of individual variables (e.g., personality). Despite the reduction of time and costs of online questionnaires, we cannot control the response time and spontaneity of respondents. Also the length of the questionnaire may discourage its filling in, or justify an incomplete filling.

In sum, understanding the impact of CQ and MP on the performance of individuals, teams and organizations in multicultural contexts is an asset to global organizations and societies. On the other hand, the development of effective IC allows the definition of conflict strategies and negotiation management in contexts characterized by diversity and multiculturalism.

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (