Europe will undoubtedly remember 2015 as the year of the evolving refugee crisis. As primary transit zones, many Eastern European countries got involved in this crisis without any significant prior experience in its recent history regarding refugees. It became a politically relevant and highly controversial question in these countries, how to respond to the large wave of immigrants and refugees travelling through the region. The question was framed as a moral dilemma between the moral responsibilities to defend the country from the threat of mass-immigration and to help people in need.

At the same time, as it is indicated by recent research findings about motivated social cognition and moral psychology, moral judgments are influenced by personal motivations and psychological dispositions that also affect intergroup attitudes (Federico, Weber, Ergun, & Hunt, 2013; Kugler, Jost, & Noorbaloochi, 2014; Milojev et al., 2014). Therefore, these moral judgments are necessarily not impartial. Building upon the recent joint research of the dual process model of prejudice and ideologies and moral foundations theory (Federico et al., 2013; Hadarics & Kende, in press; Kugler et al., 2014; Milojev et al., 2014; Radkiewicz, 2016), we attempt to support the assumption that the negative perception of outgroups is related to moral concerns that are derived from individual level dispositions.

The Dual Process Model of Prejudice [TOP]

According to the Dual Process Model of Prejudice and Ideologies (DPM), all our socially and ideologically relevant beliefs can be arranged along two well distinguished attitudinal dimensions: right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2009, 2010). Both dimensions have their unique motivational background, and have very different environmental and personality-related bases. In the case of the first dimension, the main motivation is to establish and maintain order, security, and stability in the social environment. Consequently, all the beliefs and attitudinal preferences belonging to this dimension help reach this goal. The authors suggested that this attitude cluster can be identified by the concept of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) by Altemeyer (1981) with the diagnostic characteristics of conventionalism, submission to conventional authorities, and hostility towards non-conventional outgroups. The primary motivation for the second dimension is to seize and maintain power within the existing social hierarchy. According to the DPM, this attitudinal dimension can be described by the concept of social dominance orientation (SDO), defined by Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, and Malle (1994) as the degree of personal preference for hierarchical and unequal intergroup relations.

As the DPM suggests, the negative perception of a certain outgroup can be originated from two motivational bases, it might be either RWA-based or SDO-based. While RWA predicts negative attitudes towards outgroups that are perceived as a threat to security and the integrity of the given society, SDO is associated with attitudes towards outgroups that are either seriously derogated, or considered as a competitive rival in the struggle for resources or dominance (Duckitt & Sibley, 2007). Perceived threat seems to be a key component in both RWA-based and SDO-based intergroup attitudes, but with a slightly different perceptional and motivational background. Authoritarians’ intergroup attitudes are determined mainly by their judgment on whether a particular outgroup threatens the cohesion of their own ingroup, or the security of their social surroundings (Cohrs & Asbrock, 2009; Duckitt, 2006; McFarland, 2005). SDO, on the other hand, makes people more vigilant about whether a certain group threatens their dominant status in the social hierarchy (Cohrs & Asbrock, 2009; Costello & Hodson, 2011; Duckitt, 2006).

Of course, the very same group can be perceived to mean both kinds of these threats, such as in the case of immigrants. As research shows, authoritarian people are prejudiced against immigrants because they see them as a threat to the stable and predictable societal environment and ingroup cohesion, but people with high SDO hold negative attitudes towards this group because they see them as inferior or a potential competitor for social status (Cohrs & Stelzl, 2010; Craig & Richeson, 2014; Thomsen, Green, & Sidanius, 2008).

Moral Foundations and Their Relationship to SDO and RWA [TOP]

RWA and SDO do not influence only our intergroup attitudes but a wide range of other socially relevant beliefs like political and ideological attitudes, policy preferences (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Pratto & Cathey, 2002; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999), or as recent research regarding moral foundations revealed, our moral judgments are related to them too (e.g. Bostyn, Roets, & Van Hiel, 2016; Federico et al., 2013; Jackson & Gaertner, 2010; Kugler et al., 2014; Milojev et al., 2014).

The original aim of Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) was to explain the psychological mechanisms underlying the apparently different moral values and preferences of social groups like conservatives and liberals, or members of collectivists and individualist cultures (Graham et al., 2013; Haidt & Graham, 2009). According to the MFT, our moral judgments and intuitions are based on so called moral foundations which have evolutionary roots but shaped by culture forming the innate, modular foundations of moral reasoning. The theory describes five of these moral foundations: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity. These moral domains are often categorized into two broader groups: care and fairness are the so called individualizing foundations, while loyalty, authority, and sanctity constitute the binding foundations (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Graham et al., 2011). Individualizing moral foundations protects the community from individual selfishness by direct disapproval and prohibition of doing harm to others, and by making people respect the rights of others, while binding foundations achieve the same goal by binding people to cohesive groups and institutions, and creating well-defined roles within the group and the institutional system.

MFT provides an explanation for the distinct moralities of different social groups, arguing for example, that binding moral foundations are more important for conservatives and members of collectivist cultures than for liberals or members of individualist societies (see Graham et al., 2013 for a review). But individualizing and binding moralities are also related to several individual-level psychological dispositions, like RWA and SDO among others. Recent research revealed that RWA is primarily connected to binding moral foundations, while SDO has a negative relationship with individualizing morality (Federico et al., 2013; Kugler et al., 2014; Milojev et al., 2014). Furthermore, there is some evidence which supports that moral foundations are directly related to the negative evaluation of outgroups. According to Kugler and his colleagues (2014), binding moral foundations are positively related to anti-immigrant attitudes, while the associations with individualizing foundations are negative. Low and Wui (2016) reported negative relationship between individualizing foundations and negative attitudes towards the poor, whereas Smith, Aquino, Koleva, and Graham (2014) found that binding moral foundations enhanced support for the torture of outgroup members among respondents with weak moral identity.

These results underline the possibility that the perception of outgroups is determined at least partly by moral concerns. When someone forms an opinion about a particular outgroup, that opinion is at least partially formulated on how perceived characteristics of the outgroup relate to personally endorsed moral concerns and standards. The more the outgroup contradicts to the personally important moral preferences, the more threatening that outgroup becomes. But individual level dispositions like RWA and SDO might also influence what kind of moral concerns are applied when we judge how threatening a particular outgroup is. Based on this, it can be assumed that perceived intergroup threat is the product of partly moralized motivated social cognition.

The Current Study [TOP]

In our study we explore the role of individualizing and binding morality in the negative beliefs about immigrants. We assumed that the two distinct attitudinal dimensions of RWA and SDO affect the negative perception of immigrants partly through personal moral concerns. RWA is expected to boost the perceived threat that immigrants represent via binding moral foundations, because those scoring high on authoritarianism may see immigrants as a threat to the core values that bond their ingroup in a cohesive unity, creating predictability and security. On the other hand, SDO is expected to elicit perceived threat through individualizing moral foundations that are expendable for people with high SDO in order to keep immigrants in their underdog position. In sum, we predicted that the effect of RWA on the perception of immigrants is partially mediated by binding moral foundations, while the effect of SDO is partially mediated by individualizing morality.

Participants [TOP]

Our sample consisted of 403 respondents from Hungary, recruited by convenience sampling by university students who took part in an introductory social psychology course (248 female, Mage = 31.85; SDage = 13.49). According to their educational background, 39.0% held a “graduate or professional degree”, 31.5% took part in “presently ongoing university/college education”, 24.6% had completed “high school diploma”, 3.0% had completed “vocational school” and 2.0% had completed “primary education”.

Measures and Procedure [TOP]

Participants completed an online questionnaire that contained items measuring right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, moral intuitions and attitudes towards immigrants. Responses were measured on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree) in case of all items.

Right-wing authoritarianism was measured by an 11-item Hungarian version of the RWA scale (Altemeyer, 1981) translated and adapted by Enyedi (1996) (M = 2.61; SD = .89; α = .80), while for assessing social dominance orientation, we applied a shortened 11-item Hungarian version of the SDO scale (Pratto et al., 1994) constructed by Murányi and Sipos (2012) (M = 2.57; SD = .82; α = .83).

Individualizing and binding moral foundations were measured by the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham et al., 2011). The Hungarian version of the questionnaire was obtained by a translation back-translation technique (Brislin, 1980). We ran a CFA to test whether the 5 factor structure was valid in our Hungarian sample, but found a lack of fit, indicating that the original five factor structure of the questionnaire was not appropriate for our Hungarian sample (χ2 = 1708.75; df = 395; CFI = .681; SRMR = .10; RMSEA = .091). To be able to create a meaningful measure for individualizing and binding morality in the Hungarian context, we selected ten items from the original item pool of the “moral relevance” section of the questionnaire, two items for every moral foundation that seemed to capture the original meaning of these foundations in the most appropriate way, according to the Hungarian context.i Our exploratory factor analysis showed that these 10 items provided a clear and meaningful pattern, all individualizing morality items loading substantially on one factor, and all binding morality items loading on another (see Table 1). Additionally, CFA indicated that the two factor solution showed an acceptable fit to our data (χ2 = 138.53; df = 34; CFI = .918; SRMR = .06; RMSEA = .087). Thus, although we could not replicate an appropriate measure for the five moral intuitions based on the original item pool of the MFQ questionnaire, it was possible to construct a meaningful measure for both individualizing (M = 4.60; SD = .88; α = .80) and binding morality (M = 3.67; SD = .97; α = .82).

Table 1

Results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis on the Selected MFQ Items

| Item | Factor

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Whether or not someone conformed to the traditions of society | .763 | |

| Whether or not someone showed a lack of respect for authority | .749 | |

| Whether or not someone violated standards of purity and decency | .741 | |

| Whether or not someone did something to betray his or her group | .725 | |

| Whether or not someone did something disgusting | .693 | |

| Whether or not someone showed a lack of loyalty | .686 | |

| Whether or not some people were treated differently than others | .811 | |

| Whether or not someone suffered emotionally | .809 | |

| Whether or not someone was denied his or her rights | .797 | |

| Whether or not someone cared for someone weak or vulnerable | .746 | |

| Proportion of Explained Variance | 35.12% | 22.46% |

Note. Only coefficients above .30 are shown. Extraction method: Maximum likelihood; Rotation method: Promax; KMO: .818; Bartlett test: χ2 = 1308.02; df = 45; p < .001.

Perceived threat regarding immigration was measured based on eight items originally applied by Stephan, Ybarra, and Bachman (1999). These items assessed how threatening immigrants were perceived by respondents in terms of symbolic and realistic threats. Before the translation back-translation process, the original items were partly rephrased to suit the Hungarian contextii (symbolic: M = 3.55; SD = 1.34; α = .83; realistic: M = 2.85; SD = 1.21; α = .79).

Hypothesis Testing [TOP]

In order to reveal the mediating role of individualizing and binding moral foundations between RWA and SDO as an attitudinal-ideological base, and respondents’ unfavourable views about immigrants, we ran structural equation modelling (SEM). In the SEM analysis, RWA and SDO served as a level-one independent variable and were assumed to influence attitudes towards immigrants both directly and indirectly via individualizing and binding morality. Perceived threat regarding immigrants was captured in the form of a latent variable which was based on the perceived symbolic and realistic threat that immigrants mean. We used a single threat variable because of the substantial correlation between the two kinds of perceived threats (r = .63; p < .001; see Table 2). To test the potential mediator role of the two morality variables, we applied the mediation analysis strategy suggested by Macho and Ledermann (2011).

Table 2

Correlations Between Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RWA | 1.00 | .309*** | .486*** | -.340*** | .504*** | .556*** |

| 2. SDO | 1.00 | .158*** | -.367*** | .378*** | .327*** | |

| 3. Binding Moral Foundations | 1.00 | .192*** | .394*** | .406*** | ||

| 4. Individualizing Moral Foundations | 1.00 | -.190*** | -.304*** | |||

| 5. Immigrants - Symbolic Threat | 1.00 | .629*** | ||||

| 6. Immigrants - Realistic Threat | 1.00 |

***p < .001.

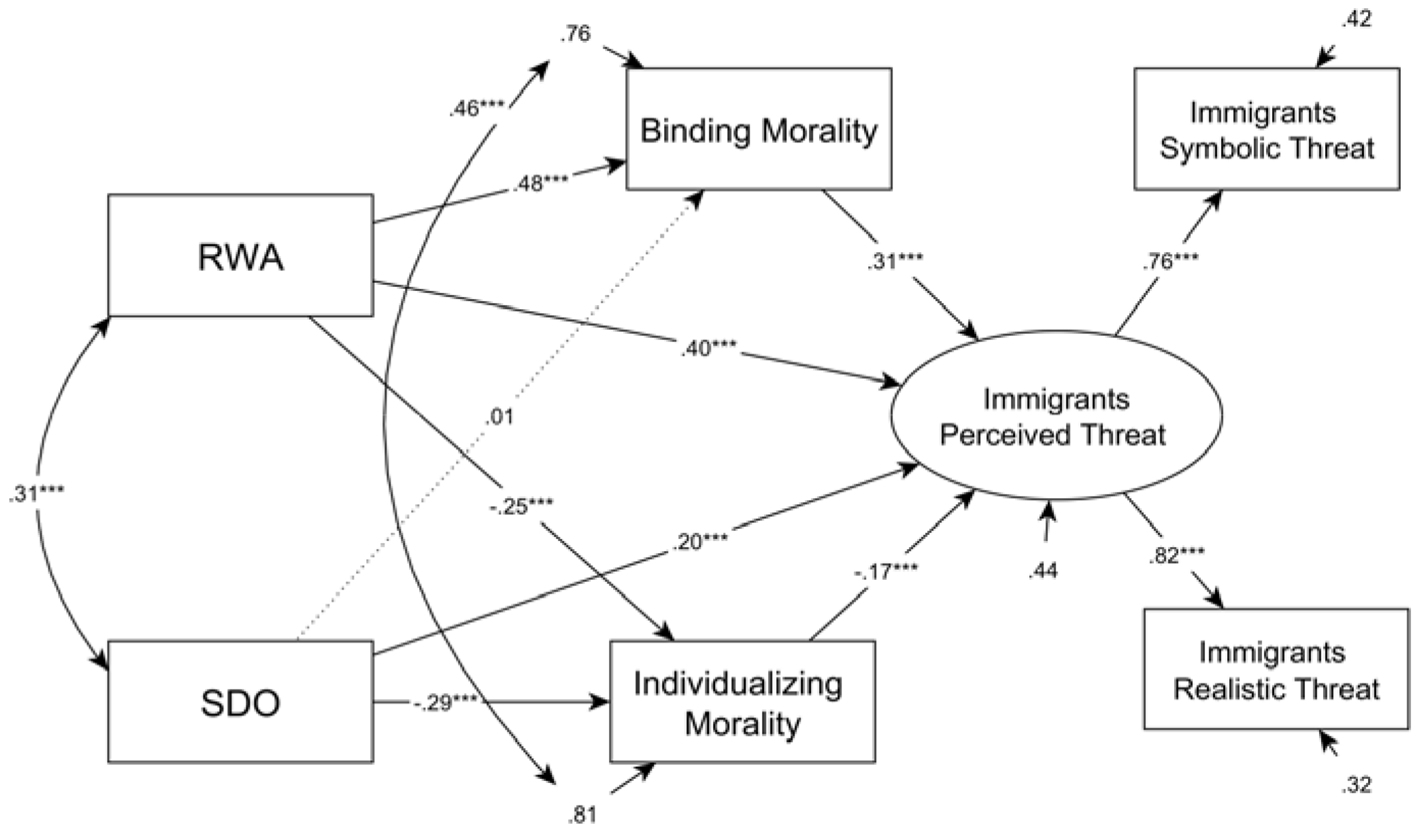

According to the results of the SEM analysis, our model showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 13.85; df = 3; CFI = .989; SRMR = .02; RMSEA = .095; see Figure 1). This model indicated that both RWA (β = .40; p < .001) and SDO (β = .20; p < .001) had a significant direct effect on prejudice against immigrants, just like both forms of morality had, binding foundations (β = .31; p < .001) as well as individualizing foundations (β = -.17; p = .001). RWA also had a direct effect on the two kinds of morality, a positive one on binding foundations (β = .48; p < .001), and a negative one on individualizing foundations (β = -.25; p < .001). SDO reduced individualizing moral foundations (β = -.29; p < .001), but did not affect binding foundations (β = .01; p = .86).

Figure 1

Pathway model explaining negative attitudes towards immigrants based on RWA, SDO, and moral foundations. Path coefficients are standardized regression coefficients.

***p < .001.

Because of the significant associations between perceived threat and the two kinds of moralities, and also between these two moralities and RWA, furthermore between individualizing morality and SDO, it seemed a reasonable assumption that RWA and SDO affected the individual level of prejudice against immigrants at least partly through moral foundations. To reveal these indirect relationships, mediational analysis was conducted with the bootstrapping technique suggested by Macho and Ledermann (2011), where we requested 95% confidence intervals using 2000 resamples. Indeed, the conducted mediation analysis showed that besides its direct effect, RWA had a significant indirect effect on anti-immigrant attitudes through both binding morality (B (unstandardized indirect effect) = .19, p = .009, 95% CI [.12, .30]), and individualizing morality (B = .05, p = .008, 95% CI [.01, .12]), while SDO had a significant indirect effect mediated by individualizing morality (B = .05, p = .013, 95% CI [.01, .12]), but not by binding morality (B = .003, p = .77, 95% CI [-.03, .04]).

Discussion [TOP]

According to our results, both RWA and SDO played a considerable role in the negative views of our Hungarian respondents about immigrants, although it is important to stress that the connection with RWA seems far more important than with SDO. In the light of the dual process model of prejudice, this indicates that the motivational force of maintaining a secure and predictable social environment surpasses the motivation to dominate the outgroups and to keep them in their underdog position. It seems that perceived threat of security and integrity surpasses the threat of losing social status and dominance. Consequently, it can be concluded that anti-immigrant attitudes were primarily rooted in fear of the unpredictable and not in envy or seeking dominance.

Our results also indicate that both RWA-based and SDO-based motivations affect perception of immigrants partly through personally relevant moral concerns. Similarly to previous research (Federico et al., 2013; Kugler et al., 2014; Milojev et al., 2014), we found that SDO was negatively related to individualizing moral foundations, which means that for respondents with a high SDO value, it was not important whether somebody had to suffer some kind of harm or injustice when they judged the moral propriety of an act. This could mean that they regarded these moral concerns expendable in order to keep the dominant position of their group within the social hierarchy. This latter presumption is supported by the results of Son Hing, Bobocel, Zanna, and McBride (2007) who found that people with higher SDO tended to make unethical decisions in an economic simulation task if that was the price for increasing their own benefits.

Not surprisingly, RWA showed a negative relationship with individualizing morality, given that aggression towards non-conventional outgroups is an integral part of the authoritarian attitude cluster. If someone threatens the social order and harmony, those scoring high on RWA might find it permissible to neglect the moral foundations of harm and justice towards these outgroup members in order to turn aside danger. Nevertheless, RWA showed stronger association with binding morality. That is not too surprising, since authoritarians make their moral judgements based on the exact values they aspire to: predictable and well-proven rules and guidelines for the social environment (tradition and purity), a coherent group that shares these rules (ingroup loyalty), and a leader who is able to guarantee the everyday functioning of these rules (authority). Since immigrants, as a non-conventional outgroup, inevitably contradict these moral values and preferences (or at least to the concrete manifestation of these values as specific personal preferences), people with a higher binding moral preference would perceive immigrants as a threat and potential danger.

What needs to be highlighted here is that moral foundations can influence social perception in a way that the very same group may be perceived strikingly differently, depending on the particular moral concerns someone relies on when evaluating a complex and ambiguous social category, like immigrants in Hungary, a mostly unknown social group to the majority of the society. Those applying the criteria of individualizing foundations (harm and justice) might see immigrants as victims of injustice who are in need of help and support, while for those relying on binding morality, immigrants might seem much more of a threat to the existing social order, harmony, and ingroup cohesion. These foundations can function as criteria for moral judgments because they are probably more chronically accessible than other cognitive elements. This is how they influence not just moral judgements, but also social perception per se.

Moral foundations are not independent beliefs, but they are closely related to broader and more general attitudinal systems, like RWA and SDO. We can claim that certain moral foundations are the specific moral outcomes of these general attitudinal dispositions. This is highly possible in the case of binding foundations, which show a great overlap with authoritarian value preferences, that is why we could regard them as specific occurrences of the RWA attitude cluster in morally relevant decisional situations (see also Kugler et al., 2014).

Individualizing foundations are a little bit different, as indicated by the somewhat weaker negative associations between this kind of moral intuition and the two attitude clusters. As it seems, individualizing moral foundations are more independent from RWA and SDO than binding moral foundations, but can be apparently inhibited by them if these foundations hinder the realization of the preferences related to RWA (security and predictability) or SDO (group dominance).

Conclusion [TOP]

The perception of certain outgroups largely depends on personal moral concerns, what regard as right or wrong, morally acceptable or unacceptable. However, moral judgements do not come as random intuitions, they are largely determined by a person’s psychological character and motivational preferences. If certain motivations surface, it can have an effect on the applied criteria of moral judgements, and that can determine how people relate to a particular outgroup.

This is a highly relevant phenomenon in the case of Hungary and other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries involved in the refugee crisis that evolved in 2015. Not being a primary destination country, unlike Western European countries, citizens of CEE had gained limited experience regarding immigration before the latest wave. That is why the social perception of immigrants could not have been based on personal experiences, but rather on motivations originating from other sources. Social and existential insecurity taking place in this region can foster authoritarian attitudes with its unique binding morality, consequently people see immigrants through the moral lens of authoritarianism, and perceive them as an additional threat to the already unstable social order. This seems to be a specific manifestation of the general fear of the unpredictable and uncertain, and supports the idea that if we want to promote a greater extent of tolerance and cooperation in these young democracies, we have to start it by developing a balanced and predictable societal environment.

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (