The value of Arts and Culture and this includes in this broad category Performing Arts, has been debated for a while and the evidence so far has provided extrinsic benefits in social and economic areas as well as intrinsic benefits such as health and wellbeing. They have also been instrumental in demonstrating key benefits in nurturing cultural experiences, aesthetic pleasure which although considered somewhat private have nonetheless brought enriching experiences when these have been considered as wholes rather than their single individual parts (Arts Council, 2014).

There are a number of studies that have suggested that attendance and participation to arts and cultural events have a positive impact on some health conditions and their associated symptoms. For example, on human cognition such as memory, listening and expressive language skills, emotional recognition and emotional self-regulation; these as a result can have an impact on physical wellness but also self-esteem, confidence and one’s own perception in the ability to manage one’s own changes in thinking and behaviours/actions (CASE: The Culture and Sport Evidence Programme, 2010; Connolly & Redding, 2010; Cuypers et al., 2012; Houston & McGill, 2012).

Physical and psychological benefits through participation and collaboration in Dance, have been demonstrated through improvements in individuals’ motor coordination, balance, flexibility, strength and gait and again as a result improvements have been observed particularly in people affected by Parkinson and people affected by other mental health conditions such as depression (BUPA, 2011; Connolly & Redding, 2010; Dibble, Addison, & Papa, 2009; Earhart, 2009).

The social aspect of dance also highlights benefits in enhancing overall wellbeing by reducing potential risks which are often associated to loneliness, isolation and poor social identity (Arts Council, 2014). Some studies demonstrate that participation in dance can also enhance a sense of expression and identity, and a sense of achievement in having learnt potential new skills (BUPA, 2011).

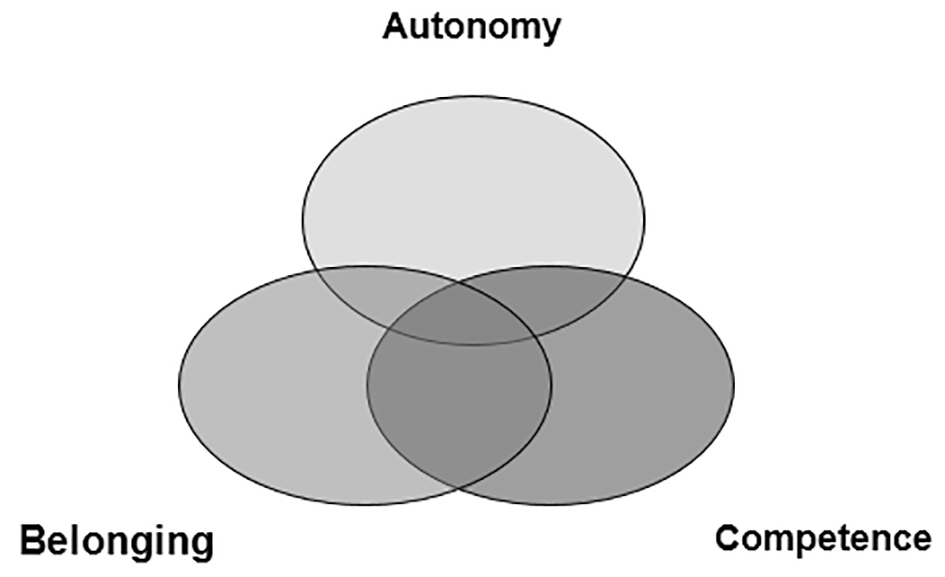

There are some fundamental psychological needs which are recognized as key elements for reaching psychological health and well-being. Self-determination theory (SDT) by Ryan and Deci (2017) suggests that intrinsic human motivation and thus growth is driven by three key psychological needs: 1) autonomy, 2) belonging and 3) competence (see Figure 1 below). The first is explained as the universal need to be our own agent and in harmony with one’s self; motivation is fostered and increases in individuals whose sense of choice and options are nurtured, rather than being dictated and ordered by external figures and agents. The second, belonging (or relatedness) is known as the universal need to have connections, and interactions and experiences with others; the third, competence, is explained as an intrinsic motivation to experience a sense of control over the outcome of a task and ultimately a sense of achievement and accomplishment.

When looking at special educational needs and how participation and engagement can be fostered in population with special and additional needs, where cognitive, social emotional skills often are seen as barriers to their development, contributions from performing arts and arts in general ought to be better explored and perhaps applied in a more systematic way where the process of leading to a performing outcome, could be adopted as the process and method through which skills are taught and presented. Performing is here presented as the ability to functionally execute, “perform” a number of learnt skills. This is something we all do – and take for granted – on a daily basis.

This editorial aims to present a methodology which adopts an analysis of the presented three psychological needs from the aforementioned SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and places them under the process – and structure – of performance and performing outcomes. Whether a drama, a music instrumental, poetry reading or a dance performance, it is the process adopted to reach the final product which underlines and holds its benefits.

Method [TOP]

In this section this editorial aims to present and discuss within the self-determination theory by Ryan and Deci (2017), how the three recognized basic psychological needs (see Figure 1) can be nurtured through a process of performing: script creation, rehearsals and the live performance. It then aims to present and explain the value and the benefits of these three basic psychological needs that are also applicable to autistic individuals and how a process of performing composition can strengthen some of the barriers associated with the condition.

Figure 1

Basic Psychological Needs from SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Autonomy: Working Towards a Script [TOP]

Social Communication and social interaction skills with impairment in imagination have been identified as the well-known Triad of Impairment (Wing & Gould, 1979) in autistic spectrum conditions (ASCs). Often identified as ‘deficits’ regarding individual interests, routines and perspective taking, it can lead autistic individuals to anxious states often linked to a significant Intolerance of Uncertainty (IoU) (Dugas, Freeston, & Ladouceur, 1997). They often find social cues either irrelevant or difficult to percept and often use either literal language or non-verbal behaviours to understand others or to get others understand them. The benefits of creating a script which is born from individual interests and is scaffolded (Berk & Winsler, 1995) with sensitive and discreet support – zone of proximal development (ZPD) – (Vygotsky, 1978), can support in fostering a sense of autonomy and accomplishment by indirectly sustaining intrinsic motivation, drive and effort. These are the essential factors in the learning experience of any individual.

The script (or direction) provides also a factual predictable and structured foundation to further the creative process, as often levels of anxiety towards uncertainty are reduced as a result of an increased sense of autonomy on what will be and has been achieved. Whether this has been created through a dance, drama, or music piece, the concept or idea are the ‘lines’ or ‘steps’ or ‘notes’ providing a systematic way to nurture imagination, self-expression and even emotional self-regulation.

Areas which have been considered a challenge and are differently developed in autistic individuals, the author has observed instead autistic individuals who had never before used spoken language skills (speech), singing a full song with a microphone, reciting a piece of poetry that had meaning or dancing a sequence that expressed basic emotional states including joy, excitement, surprise, empathy and even sadness. Through the work towards a ‘script’ some autistic individuals have also been able to foster personal meaning to the activity, as the subject was, from the start, of their choice and interest.

Belonging: Rehearsals – Working Together [TOP]

This second basic psychological need relates to the universal need for human interactions, experiencing of being part of a group, and relate in some ways to others. These needs have also been recognized in autistic individuals though the way human interactions and experiences are initiated and sustained differ from other individuals. Because of the different ways in which social cues are understood by autistic individuals – literal and concrete understanding of social situations – rehearsals and practice which are consistent, systematic and predictable, can provide a way of working ‘together’ towards a common goal. This is of course pursued by each individual, but it provides an opportunity to learn about sharing spaces, tolerating the presence of others in proximity of each other, learning about turn taking skills and coping (tolerating) with each other. As again some of the ‘barriers’ identified and associated with ASCs can include attention difficulties, initiating interactions with others and being able to sustain them, rehearsals and practice provide a very effective opportunity for learning new social skills as well as consolidating that knowledge and addressing these areas of vulnerabilities which are well known in autistic individuals.

It has been observed that autistic young persons, rehearsing and supporting, cueing each other in order to complete a step, a song or a piece of drama, were able to follow a common story or script, as the rehearsals were unfolding. Young people were also able to better and more positively tolerate each other in the face of errors, by seeking support and adult prompting in achieving the desired results. It provided often an opportunity to tolerate each other differences and as a result a more positive opportunity to really working and achieving together (social skills).

Competence: Reaching the Common Goal – The Performance [TOP]

The fundamental psychological need for competence (Deci & Moller, 2005; Deci & Ryan, 1985) is suggested to be useful in understanding the impact and influences of intrinsic motivation (internal drive and desire). Competence is one’s perception in one’s own ability to hold the skills in succeeding in a specific pursuit or task/activity. When tasks are presented in an optimal learning environment and positive feedback is provided on a regular basis, individuals’ intrinsic motivation seems to be enhanced as well as promoting their sense of competence in what they are accomplishing.

It has also been noted that rewards (external drivers) tend to decrease intrinsic motivation (rather than increasing it), whereas a sense of choice seems to actually enhance the intrinsic motivation – and intrinsic enjoyment – in performing a specific task.

The performance is here explained as the final stage of the process where a final product from the point of creating a script, rehearsing and putting all together culminates in a presentation ‘live’ of the final piece of work. The performance(s) are well set in advance, with clear dates throughout the academic year. This provides a visual reassurance (and certainty of a future event) and a common goal for individuals to work towards thus potentially reducing anxiety related to unpredictability and the unknown.

The exposure to a live audience formed by family members and friends provides an element of predictability but also within the structure of the performance some elements of surprise and unfamiliarity which can be better managed by autistic individuals. The live performance, whether drama, music or dance, is also preceded by a “dress rehearsal”, which provides an added opportunity, although without the presence of an audience, on how the performance will unfold (Gough, 1993). Through a dress rehearsal a number of other life skills can be incorporated such as dressing (and undressing), using hair styles and make up, using props fostering pretend-play and imagination (Bateson, 1955); these are all areas identified again as potential areas of difficulties for autistic individuals. However, the creative and imaginary opportunities offered through drama and dance scripts, where real life situations can be presented in a make believe way, it can also enhance the experience of real life events and situations, where social and communication skills can be safely practiced and sustained for long term benefits.

The actual performance provides autistic individuals with a sense of accomplishment reinforced also externally by the audience appreciation of what has been presented – clapping after each section or number. It is quite surprising how positive responses to potential loud noises, something autistic individuals could be very sensitive to – auditory hyper-sensitivities (Bogdashina, 2010) – and clapping, have been observed, performance after performance, by autistic individuals, and their ability to really be present in that particular special moment (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Music which has been played fairly loud, and yet in a predictable manner through rehearsals, can be more positively and overall coped with. Below are some selected comments from autistic youngsters that have self-reflected on the experience of performing and what they expressed was and is a sense of achievement:

Another example where they have expressed a sense of pride and enjoyment in wearing dresses and costumes for particular dance pieces:

Another student was able to recall the process of creation of a piece of musical instrumentation with the support of technology.

“The base was done by computer and was drumming and another musical rhythm I was able to add electrical guitar on top and (with the help of the teacher) create the piece I performed”.

(Student C)

Although it is recognized that the above are anecdotal comments, they have great value in supporting the evidence-base practice for the benefits provided by the experience in participating and engaging in the performing process.

Discussion [TOP]

Performing arts have been in this editorial discussed within the context of special education and more specifically within autistic individuals. With performing arts, different forms of performance have been highlighted to include dance, drama, and music. This editorial has initially covered some of the recent evidence-based studies which suggest that participation and engagement in performing arts have significant benefits observed at educational, health and societal levels with different populations. Performance is here been proposed not as a process and source of increased anxiety (Varvatsoulias, 2017), but with the right and sensitive amount of skillful support, as a structured process through which a number of life-skills and psychological needs can actually be nurtured and further developed.

Autistic individuals will experience barriers in access their learning as a result of challenges with social interaction, social communication and flexibility of thinking; performing arts offer not only a creative but a flexible way in which a number of skills can be presented and taught by avoiding the challenges offered by very directive and rigid teaching methodologies.

Performing arts can tap into individuals’ personal worlds in a non-threatening and very nurturing, structured, visual, auditory, motoric and multi-sensory way which lends very well with autistic individuals.

Further research ought to focus on both different art forms as well as different health conditions to better and further provide robust evidence of its benefits. Longitudinal studies could be better funded in recognizing the long term benefits of Performing Arts engagement and participation. One such study is being undertaken in the UK in association with an international performing ballet company and participants affected by Parkinson. Other collaborations have also been embraced by different institutions across the UK. Arts subjects ought to be offered and taught at an early stage of a child development and certainly maintained during the following educational years (Arts Council, 2003).

With emphasis on exercise, movement and health related conditions and a growing obese child population (World Health Organisation, 2016), engagement and participation in performing arts can surely have benefits with all populations. Well-designed qualitative and mixed methods research need to further explore personal experiences of the Performing Arts participation and engagement in order to better capture the subtle benefits already observed in some studies.

Conclusions [TOP]

This editorial aimed to present the value of Performing Arts within Special Education Needs and autistic individuals as a method to systematically address some of the difficulties associated with Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASCs) and learning difficulties. Initially it presented some evidence-based research related to the great benefits of the Arts in promoting health and wellbeing, but also in education and society at large. It then discussed through a process of ‘performance’ preparation, how three well recognized basic psychological needs (SDT) can be nurtured and developed. Autonomy, Belonging and Competence having been recognized as essential psychological human needs for growth and development, they can be fostered through the process of performance conceptualization, rehearsals, and ‘live’ performance.

The stages explained throughout provide an example on how different skills – often associated with traditional academic areas – can be skillfully taught and support facilitated in overcoming some of the barriers and challenges associated with autistic learning styles. Through a process of scripts creation, rehearsals and live performances, the anxiety associated with uncertainty and unpredictability can often be better and more positively managed offering a number of opportunities with a much more conducive and positive learning environment.

Finally, this editorial also suggested practical implications for future evidence-based research where in-depth qualitative well designed research can be explored; this might provide further evidence on the actual short and long term benefits in participation and engagement in the Performing Arts, not solely seen as sources of enjoyment and entertainment – which has indeed its own value – but as an educational and societal contributor for a healthier and more content society as a whole.

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (