Asymmetry in spatial attention is well documented in the general population (Zago et al., 2017). The manual line bisection task is the most commonly used test for examining the lateralization of visual spatial attention. The task requires individual to indicate the center of horizontal lines with a pencil. The bias of the bisection from the true center determines the direction and extent of asymmetry of visual spatial attention (Ocklenburg & Gunturkun, 2017).

Neurologically intact right-handed adults typically deviated slightly to the left of the objective center regardless of hand used, a phenomenon called "pseudoneglect” (Bowers & Heilman, 1980, p.496). This leftward error is supposed to reflect a right hemisphere dominance for spatial attention allocation (for a literature review see Jewell & McCourt, 2000). Unlike adults, children tend to transect the lines to the left of the true midpoint with the left hand, and to the right with the right hand, a phenomenon called "symmetrical neglect” (Bradshaw et al., 1988, p.221; Dobler et al., 2001, p.1063; Failla, Sheppard & Bradshaw, 2003, p.353; Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003, p.156). It is suggested that this line bisection performance pattern is due to poor hemispheric interactions, related to callosal immaturity (incomplete myelination) in childhood (Hausmann, Waldie & Corballis, 2003).

There has been little research conducted on the effects of sex and handedness as subject-related variables on line bisection performance, as the obtained results are inconsistent. Regarding the sex-related effects, some researchers reported that men showed greater deviation to the left than women (Roig & Cicero, 1994), others reported that men transected the lines further to the right (Jewell & McCourt, 2000; Wolfe, 1923). Many of the researchers failed to find significant effects of sex on line bisection performance (Asenova, 2014; Bradshaw, Nettleton, Nathan, & Wilson, 1985; Brodie & Pettigrew, 1996; Chokron & Imbert, 1993; Luh, 1995; Scarisbrick, Tweedy, & Kuslansky, 1987; Shuren, Wertman, & Heilman, 1994).

Even fewer studies have explored the handedness-related effects on bisection performance. Two studies reported right pseudoneglect in both right-handers and left-handers even though right-handers produced greater leftward errors than left-handers (Luh, 1995; Scarisbrick, Tweedy, & Kuslansky, 1987). A recent study, aiming to investigate the effects of sex, handedness (left vs. right), and switching handedness on line bisection performance in 117 right-handers, 85 left-handers and 52 converted left-handers, reported that handedness and sex had no significant influence on bisection performance, but the switching handedness emerged as a variable with the power to modulate the direction of bisection bias, but its effect could depend on the subject’s sex (Asenova, 2014). The results revealed that both the right-handers’ group and the ordinary left-handers’ group demonstrated right pseudoneglect, but the converted left-handers’ group demonstrated symmetrical neglect, as this phenomenon had higher frequency in the subgroup of converted left-handed men (Asenova, 2014).

Very few studies have investigated the effects of handedness and sex on child’s performance of manual line bisection task. Unfortunately, the results were also meager and inconsistent. Some studies did not reveal sex-related (Failla, Sheppard, & Bradshaw, 2003; Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003) and handedness-related differences (Bradshaw, Spataro, Harris, Nettleton, & Bradshaw, 1988; Dobler et al., 2001; Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003) in bisection performance in childhood. In contrast, van Vugt, Fransen, Creten, and Paquier (2000) found that gender and handedness had a significant impact on the task performance in children aged 7-12 years (girls, left-handers and younger children bisected substantially to the left in comparisons with boys, right-handed, and older children, respectively), as well as Bradshaw, Nettleton, Wilson, and Bradshaw (1987) and Dellatolas, Coutin, and Agostini (1996) revealed that right-handed children showed leftward bias regardless of hand used (right pseudoneglect), but left-handed children showed symmetrical neglect.

The obvious paucity of relevant studies and the inconsistency of obtained results served as the impetus for the present study. Its main purpose was to examine the effects of sex and handedness on line-bisection in typically developing children aged 5-7 years.

Method [TOP]

Participants [TOP]

Eighty eight typically developing Bulgarian children (range 5–7 years old, Mage = 6.08 ± 0.71), 40 left-handers (18 boys, Mage = 6.61 ± 0.47) and 48 right handers (26 boys, Mage = 6.61 ± 0.24), participated voluntary in the study. Both groups were formed after a preliminary conducted assessment of hand preference.

Assessment of Handedness [TOP]

A performance test including 10 manual activities which usually are not target of social pressure for switching of left hand preference was used for handedness assessment. Each item was scored as left = –1 or right = +1, and the test score ranged from –10 to +10. All right-handed children had equal or greater than +6, and all left-handed children had equal or greater than = –6, respectively.

Line-Bisection Task: Stimuli and Procedure [TOP]

The used line-bisection task was applied in previous studies (Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003; Patston, Corbalis, Hogg, & Tippett, 2006). It comprised 17 horizontal black lines, ranging from 100 to 260 mm in length and separated by a 10-mm gap. Lines were randomly placed on the sheet, with 5 to the right, 5 to the left and 7 in the center. Children were instructed to bisect the lines with a pencil, starting from the top of the sheet. During the execution of the task, the examiner covered each line after its bisection. Each child performed the task twice, one time with each hand. The percentage of deviation for each line was calculated by the following formula: [(left bisected part – true half)/true half] x 100. Then, the average score for all lines separately for left and right hand was computed. Leftward errors were scored as negative value and rightward errors as positive.

Results [TOP]

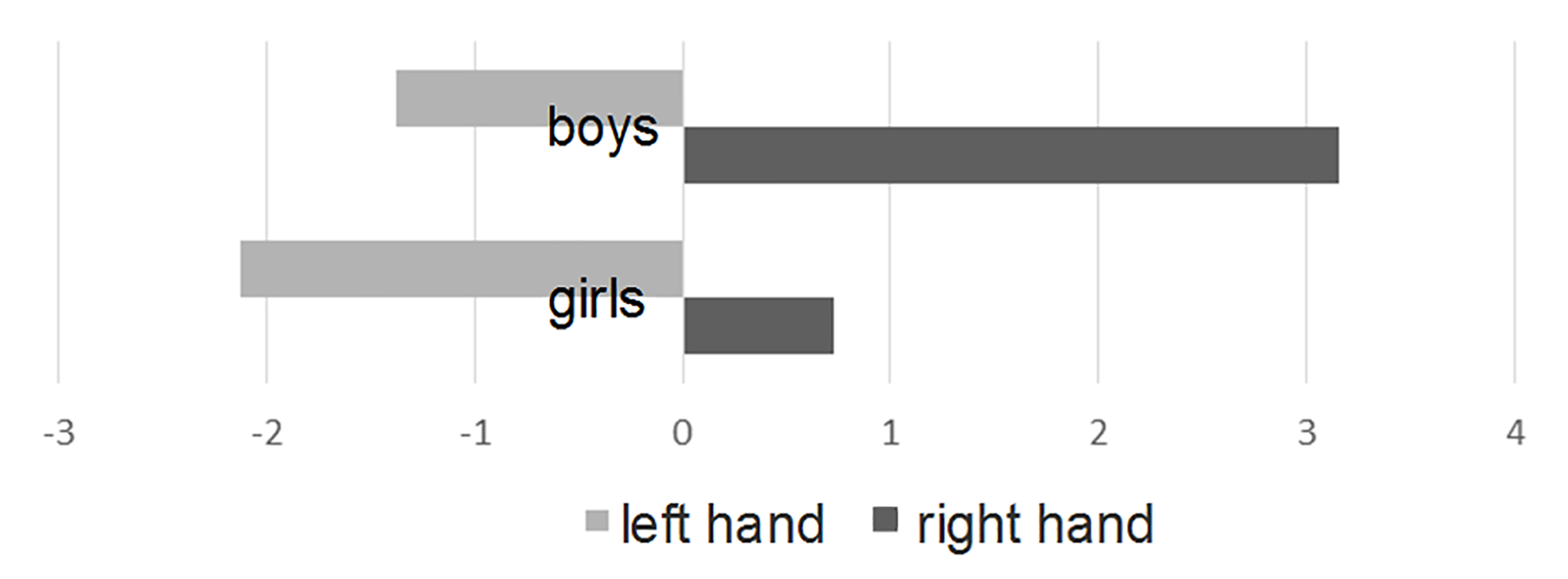

According to the Independent samples T test performed on Mean percentage deviation scores separately for each hand, both sex groups bisected to the right of center with the right hand (Mboys = 3.16, SDboys = 9.74; Mgirls = 0.73, SDgirls = 2.20; t(86) = 1.61, p = .111; Hedges’g = .344), and to the left of center with the left hand (Mboys = –1,38, SDboys = 7.21; Mgirls = –2.13, SDgirls = 2.76 ; t(86) = 0.64, p = .524; Hedges’g = .137) suggesting symmetrical neglect (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Mean percentage deviation from the objective center in the line-bisection task as a function of sex group and hand used - Negative numbers indicate leftward bias and positive – rightward bias.

As seen, girls showed greater deviation to the left of the exact midpoint of the lines when bisected with the left hand than boys, and boys showed greater deviation to the right of the exact midpoint of the lines when bisected with the right hand than girls, with the between-group differences not being statistically significant. Therefore, the two sex groups demonstrated slight and non-significant differences regarding the line bisection performance.

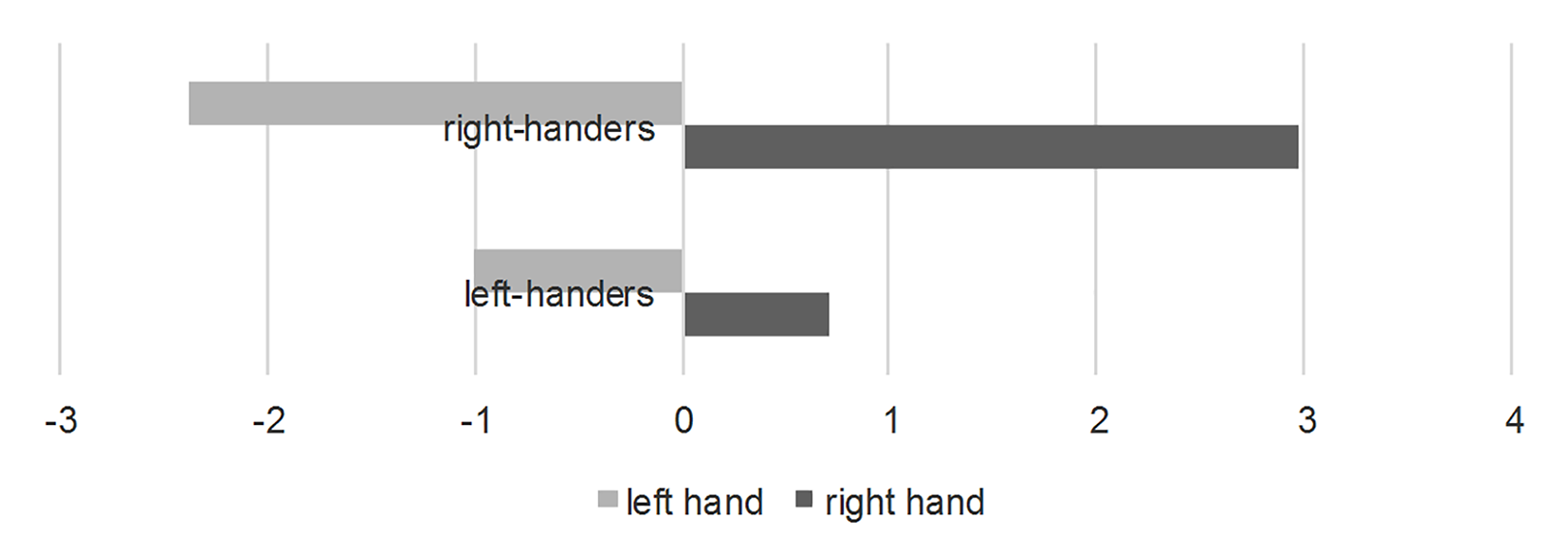

Both handedness groups also bisected right of the exact midpoint of the lines with the right hand (Mleft-handers = 0,71, SDleft-handers = 2.18; Mright-handers = 2.98, SDright-handers = 9.36; t(86) = 1.50, p = .137; Hedges’g = .321) and left of the exact midpoint of the lines with the left hand (Mleft-handers = –1.01, SDleft-handers = 2,49; Mright-handers = –2.37, SDright-handers = 6.98; t(86) = 1.17, р = .245; Hedges’g = .251) suggesting symmetrical neglect (see Figure 2). Here, the left-handers’ group bisected more accurately making smaller deviations with both hands in comparison with the right-handers’ group, but the between group differences were not statistically significant (р > .05).

Figure 2

Mean percentage deviation from the objective center in the line-bisection task as a function of handedness group and hand used - Negative numbers indicate leftward bias and positive – rightward bias.

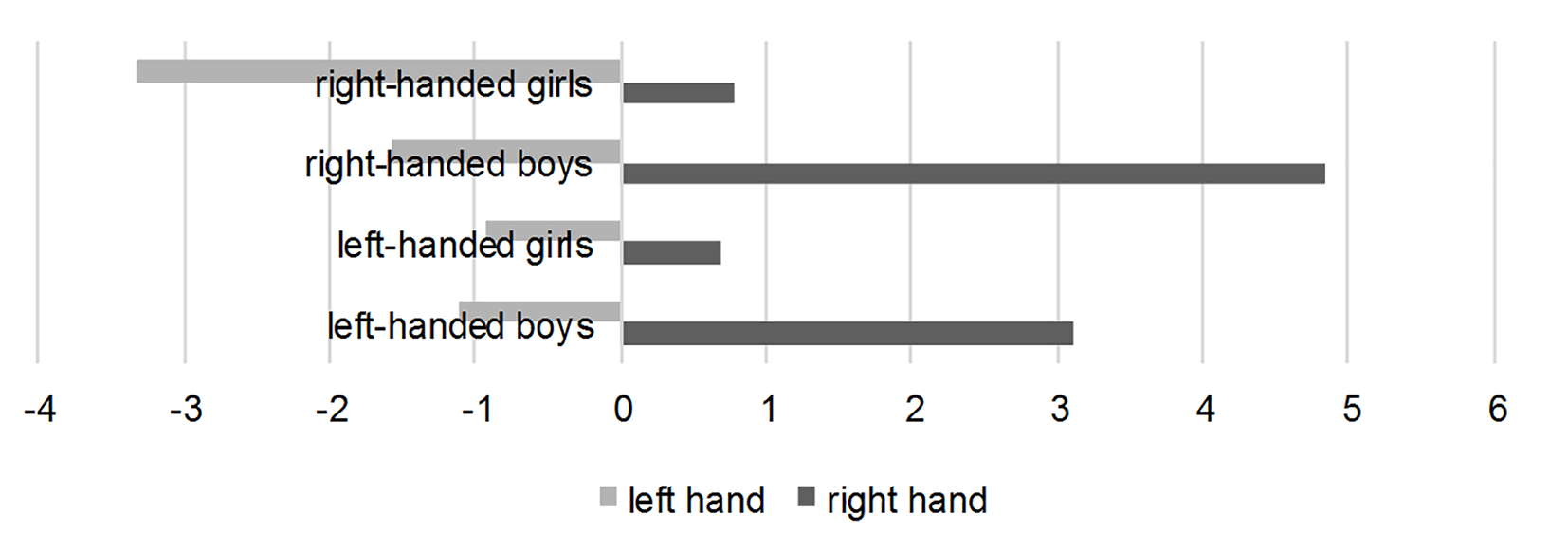

Comparison of task performances of sex-handedness subgroups revealed that all these subgroups bisected to the right of center with the right hand (Mright handed boys = 4.84, SDright handed boys = 12.22; Mright handed girls = 0.77, SDright handed girls = 2.98; Mleft handed boys = 0.72, SDleft handed boys = 3.12; Mleft-handed girls = 0.69, SDleft-handed girls = 1.00) and to the left of center with the left hand (Mright handed boys = –1.57, SDright handed boys = 9.04; Mright handed girls = –3.33, SDright handed girls = 3.19; Mleft handed boys = –1.11, SDleft handed boys = 3.34; Mleft-handed girls = –0.93, SDleft-handed girls = 1.56), suggesting symmetrical neglect (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Mean percentage deviation from the objective center in the line-bisection task as a function of sex-handedness subgroups and hand used - Negative numbers indicate leftward bias and positive – rightward bias.

As shown, the subgroups of left-handed boys and girls bisected more accurately making smaller deviations with both hands in comparison with the subgroups of right-handed boys and girls, but the between-subgroup differences did not reach statistical significance (р > .05) except the difference between the two female subgroups regarding the mean percentage deviation scores for the left hand which was statistically significant and with a large effect size (t(42) = 3.16, p = .003; Hedges’g = .956).

According to ANOVA, there was no significant main effect of handedness (for left hand F(1, 237) =1.474, p = .226 and for right hand F(1, 272) = 1.943, p = .164), sex (for left hand F(1, 218) = 0.452, p = .502 and for right hand F(1, 223) = 1.865, p = .173), and their interaction (for left hand F(1, 229) = 0.687, p = .408 and for right hand F(1, 218) = 1.814, p = .179) on mean percentage deviation scores for both hand-use conditions.

A Chi-square analysis was performed to compare the frequency of symmetrical neglect in study groups (Table 1). The results revealed higher frequency of symmetrical neglect among girls and left-handers in comparison with boys and right-handers, respectively, but differences reached significance only between the sex groups (χ2(3, N = 88) = 10.41, p = .03, Cramer’s V = .344).

Table 1

Distribution of Participants in Handedness Groups and Sex Groups Depending on the Type of Neglect (in %)

| Type of neglect | Girls | Boys | Left-handers | Right-handers | Total group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetrical neglect | 63.6% | 31.8% | 55% | 41.7% | 47.7% |

| Right pseudoneglect | 20.5% | 25% | 20% | 25% | 22.7% |

| Left pseudoneglect | 13.6% | 36.4% | 22.5% | 27.1% | 25.7% |

| Reverse symmetrical neglect | 2.3% | 6.8% | 2.5% | 6.2% | 4.6% |

| Pearson Chi-Square | χ2(3, N = 88) = 10.41, p = .015 | χ2(3, N = 88) = 1.91, p = .591 | |||

| Cramer’s V | .344 | .147 | |||

Note. Symmetrical neglect (left bias with the left hand and right bias with the right hand); Right pseudoneglect (left bias with both hands); Left pseudoneglect (right bias with both hands); Reverse symmetrical neglect (right bias with the left hand and left bias with the right hand).

It is important to note, that in addition to the most common patterns of line-bisection performance – symmetrical neglect and right pseudoneglect, left pseudoneglect had an impressively high frequency in the studied samples, even higher than the frequency of right pseudoneglect, especially in the boys’ group (36.4%).

Discussion and Conclusions [TOP]

The results of the present study confirmed the previous findings that children 5-7 years old demonstrated symmetrical neglect when bisecting horizontal lines – a leftward shift with the left hand and a rightward shift with the right hand in line bisection (Bradshaw, Spataro, Harris, Nettleton, & Bradshaw, 1988; Dobler et al., 2001; Failla, Sheppard, & Bradshaw, 2003; Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003), more pronounced in left-hand performance (Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003) which is consistent with the suggestion that this pattern of manual line-bisection task performance reflects a lack of callosal transfer of the information at this age period (Hausmann, Waldie, & Corballis, 2003). Therefore, the study findings are in agreement with ontogenetic research h of functional hemispheric asymmetries which reveal obvious differences between children and adults in the performances of lateralized tasks and are taken to reflect developmental changes due to the morphological and functional maturity of the brain (Crone & Ridderinkhof, 2011; Luders, Thompson, & Toga, 2010; Simernitskaya, 1985).

With respect to the effects of handedness and sex on line bisection performance in this age period, the present results showed no significant effect of these subject-related variables and their interaction on mean percentage deviation scores at the group level, but showed a significant effect of sex on the frequency of symmetrical neglect, with higher frequency in girls than in boys.

Although insignificant, the differences between the four sex-handedness subgroups have marked out a tendency of slightly greater precision and smaller intermanual asymmetry in the subgroups of left-handed boys and girls in comparison with the subgroups of right-handed boys and girls.

In conclusion – taken together our results indicate a slightly less lateralized visual spatial attention in left-handed and female children aged 6-7 years than in right-handed and male children at the same age, providing some support, although weak, to the suggestion for less lateralized cerebral functions in non-right handed subjects than in right handed subjects (Annett, 2002; Asenova, 2014; Hirnstein, Hugdahl, & Hausmann, 2018; Kimura, 1999; Witelson, 1989), and in females than males (Godard & Fiori, 2010; Gur et al., 2000; Hirnstein, Hugdahl, & Hausmann, 2018; Kimura, 1999; Witelson, 1989).

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (