Zimbardo (1977) considered shyness (in his USA studies) to be a common personality characteristic, with some evaluations of shyness feelings estimated to be as high as 90% of the population. And more recent surveys have shown nearly half (up to 48%) of the populace affected (Heiser, Turner, & Beidel, 2003). Shyness has also been regarded as a personality trait that could interfere with social interactions (Melchior & Cheek, 1990), job performance (Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2010), and career progress (Phillips & Bruch, 1988). This indicates that managers could have difficulty supervising shy people who experience social and professional problems at work.

Although there is a considerable literature on shyness as a social problem that starts in childhood (e.g., Rubin & Coplan, 2010), or as a clinical condition (Lane, 2008), and despite work indicating that shyness is negatively associated with auspicious social interactions as well as with some career-related behaviors (Moscoso & Salgado, 2004), there has been little empirical research that explored how shyness among adults could be managed in the workplace. This research gap is of interest because previous studies have not addressed the possibility that problems with adult shyness could be alleviated by factors such as organizational socialization, which should enable shy employees to be more successful at work and in their careers.

In theory, managers could help employees become socialized into any organization by providing good training, helping them understand their organizational roles, facilitating interactions with their coworkers, and generally helping them adjust to the ways the organization operates (Taormina, 1997). Thus, the aims of the current study were to (1) gain a clear understanding of the difficulties shy employees face in the workplace, (2) examine the relationship between shyness and career success, and (3) determine whether organizational socialization could beneficially moderate the relationship between shyness and subjective career success.

Shyness Defined [TOP]

Shyness has been defined as a personality trait that is characterized by anxiety, fear of new and different social situations, and reluctance to take action because shy people feel awkward and nervous when they are among other people (Cheek & Buss, 1981). According to Condon and Ruth-Sahd (2013), shyness can hamper the development of social skills, potential capabilities, creativity, and responsiveness in social interactions with others, and, thus, shy people might be considered unsociable or unfriendly by other people. There is also considerable evidence that shy people tend to be nervous and averse to social interactions (Leary, 1983a,b), including in personal conversations (Buss, 1980). Shy people also experience personal problems such as negative self-worth (Pilkonis, 1977), increased feelings of loneliness, and low levels of social affection (Phillips & Bruch, 1988).

Shyness in Relation to the Workplace [TOP]

Shyness is a concern at work because shyness is a personal characteristic that inherently relates to social situations; and organizations are composed of groups of people who must interact with each other in the daily execution of their work-related responsibilities. Also, as it has been estimated that as many as 90% of the population experience some degree of shyness (Zimbardo, 1977), it is inevitable that there will be shy employees in the workplace and that they would likely encounter some types of difficulties at work.

In particular, shy people experience more shame and embarrassment than non-shy people (Crozier, 1990), especially among strangers, in novel situations, when in the presence of high-status others, as well as during formal occasions (Buss, 1980). Yet, organizational settings often involve strangers (e.g., customers), and require working in new surroundings (e.g., job transfers). Likewise, employees are often in the presence of higher-status people, namely, supervisors, managers, and company executives, and there are various formal occasions, such as company meetings, banquets, seminars, and conferences, that employees must attend.

Also, shy people often experience high peer rejection (Leary & Buckley, 2001), low self-esteem (Leary, 1983b), and thoughts of escaping social situations (Zimbardo, 1977), and they worry about their poor performance (Kacmar, Carlson, & Bratton, 2004) and about other people’s evaluations of them (Pilkonis, 1977). These circumstances have special relevance to the work environment because everyone in the workplace must interact with coworkers, as well as with supervisors and managers who hold higher-level positions, and every employee must undergo periodic evaluations of his or her performance. Hence, shyness can have considerable potential to contribute to problems in career development.

Therefore, it seems likely that shyness could have negative consequences for shy employees in the workplace. Although empirical research on this topic has been limited, evidence for this follows a logical trail. That is, Kishor (1981) noted that certain personality traits, particularly self-esteem and locus of control, can, for high self-esteem and internal locus-of-control people, play a role in helping their career progress. But shyness is characterized by low self-esteem (Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001) and an external locus-of-control (Crozier, 1995), suggesting that shyness might hinder career progress. Similarly, performance evaluations have typically been considered essential to organizations, to have important implications for employee career success, and to be virtually unavoidable (Roberts, 2003).

Furthermore, Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley (1990) found that good job performance had direct positive effects on promotability assessments and career success. Yet, Moscoso and Salgado (2004) found shyness to be inversely related to job performance, that is, compared to their non-shy coworkers, shy employees had significantly worse scores on task performance, contextual performance, and overall job performance.

Research Model [TOP]

This research was designed to investigate the relationship between shyness and subjective career success (as a theoretical “outcome”) among adult working employees; and used the domains of organizational socialization (training, understanding, coworker support, and future prospects) as possible moderators of this relationship. Additionally, emotional intelligence, self-confidence, and emotional exhaustion were examined to assess their relationships with shyness because they are personal factors that could affect employees in the workplace. These variables, including the hypothesized socialization moderators, are each defined and described below along with the rationale for their inclusion in this study.

Subjective Career Success [TOP]

Gattiker and Larwood (1986) saw subjective career success as a person’s evaluations of his or her career that are based on one’s own job-related criteria and perceptions of what is experienced at work. Such evaluations can be objective or subjective. Objective aspects include observable factors, such as salary and job position (e.g., London & Stumpf, 1982); but some individuals who appear to be outwardly successful sometimes feel that they have not achieved much in their careers (Korman, Wittig-Berman, & Lang, 1981). Therefore, there is increasing research that has focused on subjective career success, which refers to the extent that people feel they have reached a level of achievement that gives them a sense of accomplishment, and which can be measured by their own assessment of the success they have with their careers (e.g., Greenhaus et al., 1990).

It has been argued that subjective career success can be a crucial factor because it could influence not only workers but also organizations (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999). This becomes important for management because of the problems that shy employees face in the workplace, including poorer job performance (Moscoso & Salgado, 2004). In early theorizing on this topic, Phillips and Bruch (1988) argued that shyness is a personality factor that could affect one’s career development. In support of that idea, Cheek and Melchior (1990) found that shyness was negatively related to thoughts about having chosen the right profession for both males (r = -.43, p < .01) and females (r = -.40, p < .01), which suggests that shy employees might experience sufficient difficulty in any given workplace, such that they are unsure whether they are in the right occupation.

As further evidence, if extraversion can be regarded as a personal characteristic that is the opposite of shyness, Ng, Eby, Sorensen, and Feldman (2005) found (in a meta-analysis of relevant studies in the literature) that extraversion was positively and significantly correlated with both objective and subjective measures of career satisfaction. That was confirmed by Sutin, Costa, Miech, and Eaton (2009), who also found that intrinsic (subjective) career success was significantly and positively related to extraversion. These results imply that shy employees would have lower levels of career satisfaction, or career success.

Emotional Intelligence [TOP]

Salovey and Mayer (1990) defined emotional intelligence as “the subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action” (p. 189). In other words, it is the ability to accurately and efficiently process socio-emotional information and to perceive, understand, recognize, and regulate one’s own emotions and the emotions of others. Regarding shyness, research found it to be significantly and negatively correlated with emotional intelligence among students (Márquez, Martín, & Brackett, 2006), and, according to Gerits, Derksen, and Verbruggen (2004), this relationship may also be implied to exist for working adults.

Mayer and Salovey (1997) thought that people with high levels of emotional intelligence can process emotionally related information in a way that makes it easier for them to feel happier and more successful in life. Moreover, whereas individuals with high levels of shyness tend to have difficulties with their personal relationships (Leary, 1983b) and career-related behaviors (Phillips & Bruch, 1988), there is reason to believe that shyness could contribute to difficulties in relating to other employees. Therefore, emotional intelligence was tested for its association with shyness among employees at work.

Self-Confidence [TOP]

According to McClelland (1985), self-confidence refers to the degree of one’s perceived probability of success at a task. But shy people have been characterized as having low levels of self-confidence (Manning & Ray, 1993). Furthermore, Cheek and Briggs (1990) regarded self-confidence as the opposite of shyness, and Barbalet (1996), who traced this idea to Darwin (1965), concluded that “The function of confidence, then, is to promote social action” (p. 77). In other words, shy people have less self-confidence, which means they are less likely to initiate social interactions, and research has confirmed that shy people are low in social skills (Miller, 1995).

Those classical characterizations of self-confidence imply that shyness could hamper an employee’s job success because one often needs to interact with other people at work. That is, being self-confident could increase one’s motivation to and probability of achieving career success (Bénabou & Tirole, 2002). However, as the literature on shyness and self-confidence typically focused on children (Fallah, 2014), relatively little is known about the relationship between shyness and self-confidence for adults, especially among employees in the workplace. Therefore, if shy people worry about being evaluated, and they fear rejection, then they would likely have less self-confidence at work.

Emotional Exhaustion [TOP]

According to Maslach and Jackson (1981), emotional exhaustion is the central and most critical facet of burnout, namely, it is the emotional drain that results from work demands, and which exhausts personal resources, making one feel emotionally depleted. Logically, if shy people are frequently worried about their social interactions and being negatively evaluated, they would have higher levels of emotional strain in general, and especially in the workplace where they must interact with coworkers and where they are evaluated by the people for whom they work. In other words, it seems likely that shy people could be more vulnerable to burnout than non-shy people.

Kalliopuska (2008) empirically tested this association and found a significant positive correlation between shyness and burnout (r = .28, p < .001). Thus, it may be surmised that shy employees in the workplace would expend considerable amounts of emotion in dealing with coworkers, managers, and/or administrators, which could result in increased emotional exhaustion. This idea was empirically tested.

Organizational Socialization as a Moderator [TOP]

Organizational socialization is “the process by which a person secures relevant job skills, acquires a functional level of organizational understanding, attains supportive social interactions with coworkers, and generally accepts the established ways of a particular organization” (Taormina, 1997, p. 29). This definition implies that socialization could play an important role in helping employees become successful at work (as confirmed by Taormina & Bauer, 2000), and possibly achieve their career goals. But there has been a lack of research on whether socialization can help shy individuals achieve greater career success. This may be an important concern for management because research has shown that shy students were less likely to participate in behaviors considered necessary for career development (Phillips & Bruch, 1988).

This raises the question of whether organizational socialization could benefit shy employees, and if it might act as a moderator. For example, Song and Chathoth (2010) found that socialization interacted with self-efficacy to significantly influence students’ job satisfaction and their intent to return to a job where they had worked as interns. In other words, higher levels of organizational socialization enabled people with low self-efficacy to feel greater satisfaction with their jobs. To the extent that this idea could be applied to shy employees, organizational socialization theory might suggest that workers who are offered meaningful socialization in their employing organizations should be able to socialize more effectively, with a greater likelihood of doing well at work despite their shyness. This, in turn, could give them a more positive view of their ability to achieve career success.

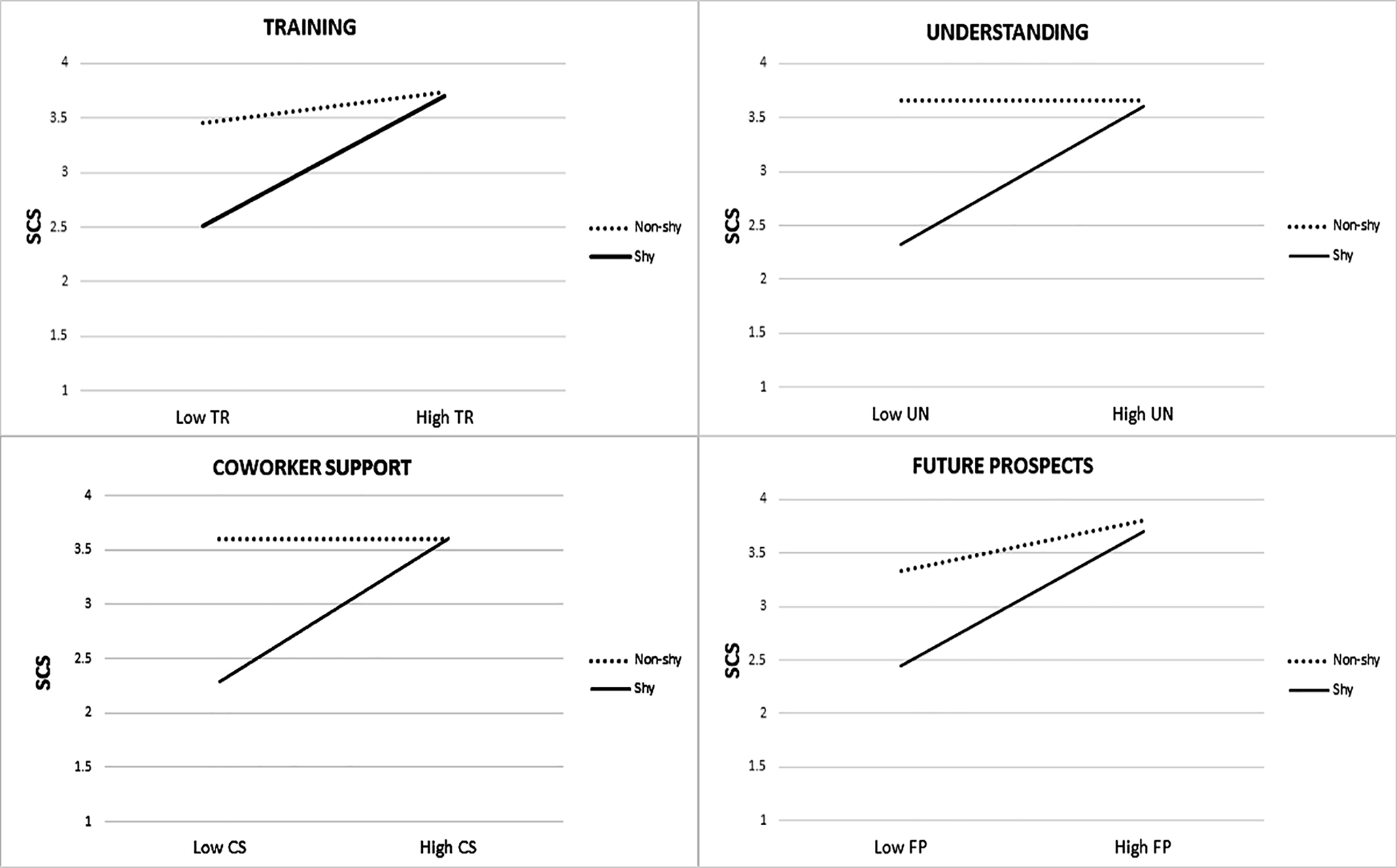

The foregoing suggests testing the interactive effects of shyness and the organizational socialization domains of Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, and Future Prospects on employees’ career success. For all interactions, it was theorized that (1) there would be an overall positive relationship between the socialization domains and career success, and (2) that shy employees would benefit more because (a) they start at a lower level of perceived career success and (b) they would have a greater appreciation of their organizations’ socialization efforts to address their specific needs.

Training [TOP]

Training is defined as “the act, process or method by which one acquires any type of functional skill or capacity that is required to perform a specific job” (Taormina, 1997, p. 31). But shy employees tend to be underachievers in their careers because of their high levels of anxiety and worry about their behaviors (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988). However, research has shown that good training can significantly reduce work-related anxiety (Taormina & Law, 2000). Thus, if training increases job effectiveness, which can increase the probability of achieving career success; and if shy employees start with a deficit in perceived career success, they should be helped in their career success by good training.

Understanding [TOP]

Understanding is defined as “the extent to which an employee fully comprehends and can apply knowledge about his or her job, the organization, its people, and its culture” (Taormina, 1997, p. 34). Understanding is necessary for good socialization, which, in turn, should improve career success, but shy employees demonstrate less career information seeking (Hamer & Bruch, 1997) and less career development behaviors (Phillips & Bruch, 1988), which could impair their career success. Consequently, when organizations help to increase employees’ understanding of their jobs, of how the organization functions, and of the people who work there, then shy employees should have increased perceived career success.

Coworker Support [TOP]

Coworker Support refers to “the emotional, moral or instrumental sustenance which is provided without financial compensation by other employees in the organization in which one works with the objective of alleviating anxiety, fear, or doubt” (Taormina, 1997, p. 37). This factor is clearly related to personal relationships. It is well known that shy people have difficulty with personal relationships because they are socially anxious and avoid making contact with others, which can interfere with their career development (Phillips & Bruch, 1988). It is therefore expected that shy employees will appreciate high levels of moral and emotional support from colleagues, and thus have greater perceived career success.

Future Prospects [TOP]

Future Prospects is “the extent to which an employee anticipates having a rewarding career within his or her employing organization” (Taormina, 1997, p. 40). Concern about future prospects in one’s career is relevant to all people regardless of their level of shyness because it refers to better pay, promotions, and other opportunities offered by a company. But shy employees worry about their poor performance (Kacmar et al. 2004) and about being evaluated (Pilkonis, 1977). This means they would worry about having a successful career, which could lead shy people to have lower expectations about their future careers. Thus, shy employees might have more appreciation of organizations that offer them positive future prospects in their careers. And this should manifest in an increased level of perceived career success when they are offered additional opportunities for good future prospects.

H(8): Shyness and Future Prospects will interact to influence Subjective Career Success, such that the relationship between Future Prospects and Subjective Career Success will be more positive for shy employees than non-shy employees when Future Prospects is high rather than low.

Taken together, the four organizational socialization domains could make the work setting a more agreeable place to work for shy individuals, and help them fit better into the organization by making them more efficient and successful at work. Thus, organizational socialization could positively moderate the association between shyness and career success.

Method [TOP]

Participants [TOP]

The participants were 375 (172 male, 203 female) adult, full-time employees aged 18 to 51 years (M = 26.68, SD = 5.20) in various occupations and many kinds of organizations in several cities in China. For their marital status, 250 were single and 125 were married. For completed education, 6 had primary school, 56 secondary school, 283 a bachelor degree, and 30 a master degree or higher. For monthly income (in Chinese RMB), 37 earned less than 1,000; 154 earned 1,000-2,999; 140 earned 3,000-4,999; 40 earned 5,000-6,999; and 4 earned 7,000-8,999. For geographic location, all the employees were from organizations in cities in three regions of northeast, central, and southeast China.

Measures [TOP]

Several scales were adopted (or items compiled) to measure the variables. For items from multifaceted scales, only items for the main concept were selected; and, to strengthen some measures, a few new items were added that focused on the central constructs. Back-translation was used to achieve language equivalence from the original English to Chinese (pilot tests prior to data collection found all scales reliable, with all the Cronbach alphas > .70). Unless otherwise noted, a 5-point Likert-type response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was used. In the descriptions, an [R] indicates a “reverse-scored” item. All scale reliabilities were tested by Cronbach alphas. Also, some demographic variables (gender, age, marital status, education, and monthly income) were included for exploratory purposes, or to test the scale validity vis-à-vis correlations in previous studies.

Shyness [TOP]

Shyness was measured using a 10-item scale. Four items were from the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae 1992) Extraversion scale, but only the reversed items were selected because shyness may be regarded as being the reverse of extraversion. The items were: “I always wait for others to lead the way,” “I like to keep in the background,” “I do not like to draw attention to myself,” and “I always hold back my opinions.” Two items were from the Cheek and Buss (1981) shyness measure, namely, “I find it hard to talk to strangers” and “I feel nervous when speaking to someone in authority.” And four items were newly created to add depth to the measure, i.e., “I am shy when meeting someone for the first time,” “I am actually a very humble person,” “I am a shy person,” and “I prefer that other people take charge of things.” The Cronbach alpha reliability of this scale was .82.

Subjective Career Success [TOP]

Some researchers have argued that there is a scarcity of adequate measures of subjective career success (Oberfield, 1993). Consequently, Subjective Career Success was measured using a newly created 5-item scale. These items were “At this point in time, I am very successful in my career,” “Compared to my peers, I am at a good place in my career,” “I am well on my way to reaching the goals I set for my career,” “I am very satisfied with the successes I have attained in my career,” and “Compared to my colleagues, I have a very successful career.” The reliability of this new scale was .86.

Organizational Socialization [TOP]

Organizational socialization was measured using the four 5-item subscales from Taormina’s (2004) Organizational Socialization Inventory (OSI). Sample items were: For Training, “This organization has provided excellent job training for me”; for Understanding, “I know very well how to get things done in this organization”; for Coworker Support, “My relationships with other workers in this company are very good”; and for Future Prospects, “There are many chances for a good career with this organization.” The reliabilities were: Training = .90; Understanding = .82; Coworker Support = .81; and Future Prospects = .87.

Emotional Intelligence (Control Own Emotions) [TOP]

This was a 5-item scale, with four items from Brackett et al.’s (2006) Emotional Intelligence Scale, i.e., “I know how to keep calm in difficult situations,” “I can quietly handle problems that would upset most other people,” “I can handle stressful situations without getting nervous,” and “I have problems dealing with my feelings of anger” [R]. And one item from Schutte et al.’s (1998) Emotional Intelligence Scale, i.e., “I have control over my emotions.” This scale’s reliability was .78.

Self-Confidence [TOP]

This was a 10-item scale. Four items were from Lane, Sewell, Terry, Bartram, and Nesti’s (1999) Self-Confidence Scale, e.g., “I feel confidence in myself.” Three items were from Kolb’s (1999) Self-Confidence Scale, e.g., “I have confidence in my own decisions.” Two items were from Hirschfeld et al.’s (1977) Lack of Social Self-Confidence Scale, e.g., “I am very confident about my own judgments.” And one item was from Day and Hamblin’s (1964) self-confidence measure, i.e., “I usually feel that my opinions are inferior” [R]. All the items were selected because they focused on introspective self-confidence (rather than a social context). This scale’s reliability was .88.

Emotional Exhaustion (Burnout) [TOP]

The 9-item Emotional Exhaustion subscale of the Maslach and Jackson (1981) Burnout Inventory was used. A sample item was “I feel emotionally drained by my work.” The scale reliability was .84.

Procedure [TOP]

A random sampling, cross-sectional method was used because it was thought that significant effects found across many organizations would lend validity to the findings. Thus, the intervention method was used to randomly select respondents in public squares and on sidewalks of busy commercial centers frequented by working people. That is, by random number generation, each nth person passing by was selected. Burns and Bush (2005) explained that this method assures there is no systematic order of attitude, characteristic, or type among people walking around different parts of a city, and, by selecting people who are not in groups, and from different parts of the cities, random selection could be achieved.

Ethical approval was obtained from a university research ethics committee before the study was conducted. Also, guidelines for research ethics of the American Psychological Association were followed, including informed consent, participants’ rights to refuse or to stop responding at any time, assuring anonymity (no names or IDs were asked or recorded), and protecting their privacy and confidentiality.

Respondents were approached in the late afternoons when employees finish work. To ensure the sample included only working people, they were asked if they were employed. Those who answered in the affirmative were told this study was about attitudes toward work, and were asked if they wanted to participate. A questionnaire was given to anyone who agreed to participate. Respondents completed the questionnaire on their own, without interruption, which took about 15 minutes. The researcher waited for each person to finish, collected the questionnaire on site, and thanked the respondent for participating. Of the 700 people asked, 375 returned fully completed, usable questionnaires, for an effective response rate of 53.57%.

Results [TOP]

Tests for Multicollinearity and Common Method Bias [TOP]

Multicollinearity was assessed by “tolerance” (1-R2) tests, where each independent variable is regressed on all the other independent variables (except for the demographics, which are often naturally correlated); and a tolerance value of less than .10 is problematic (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995, pp. 191-193). The results revealed that the tolerance values for all of the independent variables ranged from .50 to .98. Whereas the values for the variables were all well above the .10 cutoff-value, multicollinearity was not a problem in this study.

Common-method bias was tested by means of Harman’s (1976) method of factor analyzing all the variables together in order to assess whether the items fit into a single factor. It uses the maximum-likelihood factor analysis approach with a forced, one-factor solution. The resultant Chi-square value is then divided by the degrees of freedom, and a resulting ratio of less than 2.00:1 would indicate bias. For the current data, the ratio was 12.63:1, indicating that common-method bias was not a concern.

Tests of the Correlation Hypotheses [TOP]

This study was run to assess the correlations that employee Shyness had with (1) variables that were expected to be associated with it in the workplace, i.e., Self-Confidence, Emotional Intelligence, and Emotional Exhaustion, (2) Subjective Career Success, which might be negatively impacted by shyness at work, and (3) the four aspects of organizational socialization (namely, Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, and Future Prospects) as potential moderators.

The findings revealed that Shyness was negatively and significantly correlated with Subjective Career Success, r(373) = -.21 (p < .001), which supported H(1). Shyness was also negatively and significantly correlated with Emotional Intelligence, r(373) = -.20 (p < .001), which supported H(2), as well as with Self-Confidence, r(373) = -.27 (p < .001), which supported H(3). Also, a positive and significant correlation was found between Shyness and Emotional Exhaustion, r(373) = .58 (p < .001), which lent support to H(4).

Shyness had significant negative correlations with all four facets of organizational socialization: Training, r(373) = -.17 (p < .001), supporting H(5), Understanding, r(373) = -.12 (p = .018), supporting H(6), Coworker Support, r(373) = -09 (p = .080), supporting H(7), and Future Prospects, r(373) = -.18 (p < .001), which supported H(8). Table 1 shows the correlations, means, and standard deviations of the variables.

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Shyness and Test Variables (N = 375)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shyness | 2.74 | 0.63 | (.82) | ||||||||

| 2. Subjective Career Success | 3.38 | 0.72 | -.21*** | (.86) | |||||||

| 3. Training | 3.52 | 0.77 | -.17** | .48*** | (.90) | ||||||

| 4. Understanding | 3.77 | 0.61 | -.12** | .32*** | .55*** | (.82) | |||||

| 5. Coworker Support | 3.84 | 0.57 | -.09* | .28*** | .50*** | .56*** | (.81) | ||||

| 6. Future Prospects | 3.35 | 0.77 | -.18*** | .40*** | .62*** | .49*** | .42*** | (.87) | |||

| 7. Emotional Intelligence | 3.50 | 0.63 | -.20*** | .42*** | .39*** | .41*** | .43*** | .40*** | (.78) | ||

| 8. Self-Confidence | 3.72 | 0.57 | -.27*** | .40*** | .43*** | .53*** | .55*** | .40*** | .59*** | (.88) | |

| 9. Emotional Exhaustion | 2.61 | 0.65 | .58*** | -.14** | .10 | -.04 | -.14** | -.11* | -.09 | -.14** | (.84) |

Note. All the scores were on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = low, to 5 = high). Cronbach alpha reliabilities are (in parentheses) along the diagonal.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Demographic Differences [TOP]

To assess whether there were differences among the demographics, each was tested with Shyness. Age had a significant negative correlation with Shyness, r(373) = -.12 (p =.019), indicating that younger adults were more shy than older people. And a t-test on Marital Status found married people (M = 2.63, SD = 0.66) to be less shy than single persons (M = 2.81, SD = 0.60), t(373) = 2.79, p = .006. No difference was found for Gender. Also, the one-way ANOVAs that were run on Education, Monthly Income, and geographic locations (cities), found no significant differences for Shyness.

Means Comparisons Among Shy and Non-Shy Employees [TOP]

To ascertain the extent of any differences that might exist for shyness, the sample was divided into Shy (N = 128) and Non-shy (N = 247) groups (using respondents’ average scores, where scores < 3 indicated Non-shy because they disagree with descriptions of them as being shy, and scores > 3 indicated Shy because they agree with the descriptions of them as being shy, on the 5-point Likert scale). Then, t-tests were conducted to test for any differences, and the results showed significant differences for all eight variables.

That is, for the three personal variables, on Self-Confidence the Shy group (M = 3.54, SD = 0.56) scored lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.82, SD = 0.55), with a significant result, t(373) = -4.65, p < .001. On Emotional Intelligence, the Shy group (M = 3.33, SD = 0.63) scored lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.58, SD = 0.62), yielding a significant difference, t(373) = -3.80, p < .001. And on Emotional Exhaustion, the Shy group (M = 3.04, SD = 0.67) scored higher than the Non-shy group (M = 2.39, SD = 0.51), with the result again significantly different, t(373) = 10.57, p < .001.

For the five organizational variables, on Subjective Career Success, the Shy group (M = 3.20, SD = 0.72) was lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.48, SD = 0.71), yielding a significant difference, t(375) = -3.61, p < .001. On Training, the Shy group (M = 3.31, SD = 0.76) scored lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.62, SD = 0.75), which was a significant difference, t(375) = -3.83, p < .001. On Understanding, the Shy group (M = 3.67, SD = 0.55) scored lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.81, SD = 0.64), yielding a significant difference, t(373) = -2.17, p = .031. On Coworker Support, the Shy group (M = 3.74, SD = 0.50) scored lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.90, SD = 0.60), which was a significant difference, t(373) = -2.57, p = .011. And on Future Prospects, the Shy group (M = 3.12, SD = 0.75) scored significantly lower than the Non-shy group (M = 3.47, SD = 0.76) on Future Prospects, t(373) = -4.20, p < .001. All these means comparisons are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

The t-Test Means Comparisons for Shy and Non-Shy Employees on all Variables (N = 375).

| Variable | Shy Group (N = 128)

|

Non-Shy Group (N = 247)

|

t(373) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| Subjective Career Success | 3.20 | 0.72 | 3.48 | 0.71 | -3.61*** |

| Training | 3.31 | 0.76 | 3.62 | 0.75 | -3.83*** |

| Understanding | 3.67 | 0.55 | 3.81 | 0.64 | -2.17* |

| Coworker Support | 3.74 | 0.50 | 3.90 | 0.60 | -2.57* |

| Future Prospects | 3.12 | 0.75 | 3.47 | 0.76 | -4.20*** |

| Emotional Intelligence | 3.33 | 0.63 | 3.58 | 0.62 | -3.80*** |

| Self-Confidence | 3.54 | 0.56 | 3.82 | 0.55 | -4.65*** |

| Emotional Exhaustion | 3.04 | 0.67 | 2.39 | 0.51 | 10.57*** |

Note. The “Shy Group” and “Non-Shy Group” were determined by the respondents’ average scores on the Shyness measure (see Results section for details).

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Overall Regression for Subjective Career Success [TOP]

To assess the strengths of the correlations and their predictive ability for Subjective Career Success, one overall multiple regression analysis was run, with all the main variables and the five demographics as possible predictors.

The results revealed three variables as significant predictors of Subjective Career Success, F(3, 371) = 90.62 (p < .001), which explained a total of 42% of the variance. Two of the predictors were organizational socialization variables, i.e., Future Prospects, which accounted for most of the explained variance, i.e., 38%, and Training, which explained an additional 1% of the variance. Emotional Intelligence accounted for the remaining 3% of the explained variance. These results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Multiple Regression for Subjective Career Success With all Variables (N = 375).

| Predictor | Beta | ∆R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shyness | -.07 | ns | |

| Training | .12 | .01 | < .016 |

| Understanding | -.07 | ns | |

| Coworker Support | -.08 | ns | |

| Future Prospects | .46 | .38 | < .001 |

| Emotional Intelligence | .19 | .03 | < .001 |

| Self-Confidence | .08 | ns | |

| Emotional Exhaustion | -.07 | ns | |

| Gender | -.03 | ns | |

| Age | .03 | ns | |

| Marital Status | .01 | ns | |

| Education Level | -.04 | ns | |

| Monthly Income | .06 | ns | |

| Total R2 | .42 | ||

| Final F(3, 371) | 90.62 | < .001 |

Moderation Effects [TOP]

Based on the ideas expounded in organizational socialization theory (Taormina, 1997), organizational socialization is a process that can help employees become more effective workers and also be more comfortable with their work environments. To test whether this occurred with the random sample of employees in this study, hierarchical regressions were conducted that compared the Shy and Non-shy groups.

Four hierarchical regressions were run. That is, one regression was conducted for each of the four organizational socialization measures, namely, Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, and Future Prospects, which were used as the moderators, while Subjective Career Success was used as the criterion (outcome) variable. In these analyses, the demographics were entered into the regression equations first, then the two relevant main variables, namely, Shyness along with one of the four organizational socialization variables, followed by the interaction of those two variables, which represented the moderating effect. The results for all four of these regressions are shown in Table 4.

Table 4

The Four Hierarchical Regressions for Subjective Career Success With Shyness Moderated by Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, and Future Prospects (N = 375).

| Predictor | Beta | ∆R2 | p | Total R2 | Final F(4, 370) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shyness-x-Training | < .001 | .27 | 35.17 | ||

| Training | .45 | .23 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness | -.11 | .01 | < .011 | ||

| Shyness-x-Training | .12 | .02 | < .008 | ||

| Gender | -.00 | ns | |||

| Age | .02 | ns | |||

| Marital Status | -.04 | ns | |||

| Education Level | -.02 | ns | |||

| Monthly Income | -.11 | .01 | < .015 | ||

| Shyness-x-Understanding | < .001 | .17 | 19.95 | ||

| Understanding | .33 | .10 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness | -.17 | .02 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness-x-Understanding | .12 | .03 | < .001 | ||

| Gender | -.01 | ns | |||

| Age | -.07 | ns | |||

| Marital Status | -.04 | ns | |||

| Education Level | -.01 | ns | |||

| Monthly Income | .13 | .02 | < .009 | ||

| Shyness-x-Coworker Support | < .001 | .15 | 17.96 | ||

| Coworker Support | .28 | .06 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness | -.17 | .03 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness-x-Coworker Support | .20 | .04 | < .001 | ||

| Gender | .00 | ns | |||

| Age | -.03 | ns | |||

| Marital Status | -.02 | ns | |||

| Education Level | -.02 | ns | |||

| Monthly Income | -.12 | .02 | < .013 | ||

| Shyness-x-Future Prospects | < .001 | .40 | 64.16 | ||

| Future Prospects | .59 | .36 | < .001 | ||

| Shyness | -.09 | .01 | < .028 | ||

| Shyness-x-Future Prospects | .12 | .01 | < .003 | ||

| Gender | -.00 | ns | |||

| Age | .02 | ns | |||

| Marital Status | -.04 | ns | |||

| Education Level | -.02 | ns | |||

| Monthly Income | -.09 | .02 | < .018 | ||

In all four cases, the moderating effects (the interactions) yielded significant results. For Training as a moderator, a total of 27% of the variance was explained, F(4, 370) = 35.17, p < .001, where Training explained 23%, Shyness explained 1%, Monthly Income explained 1%, and the interaction between Training-x-Shyness explained the remaining 2%.

For Understanding as a moderator, a total of 17% of the variance was explained, F(4, 370) = 19.95, p < .001, where Understanding explained 10%, Shyness explained 2%, Monthly Income explained 2%, and the interaction between Understanding-x-Shyness explained the remaining 3%.

For Coworker Support as a moderator, a total of 15% of the variance was explained, F(4, 370) = 19.95, p < .001, where Coworker Support explained 6%, Shyness explained 3%, Monthly Income explained 2%, and the interaction between Coworker Support-x-Shyness explained the remaining 4%.

For Future Prospects as a moderator, a total of 40% of the variance was explained, F(4, 370) = 64.16, p < .001, where Future Prospects explained 36%, Shyness explained 1%, Monthly Income 2%, and the interaction between Future Prospects-x-Shyness explained the remaining 1%.

These results supported the interaction hypotheses, and are all graphed in Figure 1.

Discussion [TOP]

Shyness is first discussed in regard to the demographics, followed by its association with the hypothesized variables. Next is its relationship with Subjective Career Success and how the four socialization domains moderated the relationship between Shyness and Subjective Career Success. Lastly, areas for future research are suggested.

Shyness and Demographics [TOP]

The demographic variables of gender, age, marital status, education completed, and monthly income yielded only two significant results. One was for Age, which was negatively correlated with Shyness (p = .019), suggesting that living longer could reduce one’s level of shyness. This might seem to contradict some claims that shyness is a relatively stable trait (Cohen & Brook, 1987), but most previous studies tested children or clinical cases of shyness, and were not longitudinal into older age levels. As the present study focused on adults only, the findings might mean that, with age, shyness may be reduced by increased intimacy with of the opposite gender (e.g., in marriage).

Furthermore, the only other demographic that showed a significant relationship with Shyness was Marital Status. Married persons were significantly less shy (p = .006), which may confirm the idea that increased intimacy with persons of the opposite sex could decrease shyness. No other significant demographic differences were found.

Shyness and Emotional Intelligence [TOP]

The significant negative relationship between Shyness and Emotional Intelligence concurred with the idea that both variables are inherently related to interpersonal relationships. That is, in theory, shyness reflects a reluctance to be socially active for fear of being viewed by others as incompetent or socially inept (e.g., Cheek & Buss, 1981), while emotional intelligence refers to being adept at handling a variety of circumstances in dealing with other people in social situations (Goleman, 1995). And when Schutte et al. (1998) tested the association between emotional intelligence and various interpersonal relationships, they found that emotional intelligence was positively related to having social skills, good intimate affectionate relationships, and greater marital satisfaction.

In other words, the theories of both variables logically imply that shyness should have a negative relationship with emotional intelligence, and, indeed, the results in the present study confirmed that notion. Interestingly, these results appear to strengthen the idea that shyness can decrease with age, particularly with regard to marital relationships, i.e., having an ongoing, intimate relationship with another person (e.g., one’s spouse) seems to have a desensitizing effect that reduces one’s fear of interacting with people in general.

Shyness and Self-Confidence [TOP]

The findings of this study revealed a strong negative correlation between Shyness and Self-Confidence, which supported the hypothesis regarding these two variables. As pointed out by Miller and Coll (2007), the literature has suggested that shyness could lead to low levels of self-confidence (e.g., shyness could lead a person to be disregarded by peers, which could give the shy person the impression that he or she is less socially competent, and thus reduce the shy person’s self-confidence); and that low self-confidence could lead to shyness behaviors (e.g., anxious parents might implicitly teach their children to be fearful of other people, which could lead to social withdrawal, specifically, shyness). Regardless of the causal direction (which was not tested in this study), the hypothesis was based only on the idea that these two variables would be negatively correlated, as they indeed were. Thus, the strong negative correlation complies with theory, such that the result may be regarded as a (divergent) validation of the measures for these variables.

Shyness and Emotional Exhaustion [TOP]

The findings on the relationship between shyness and emotional exhaustion supported the hypothesis that there would be a significant positive association between these variables. This can be understood when it is realized that shy people, in general, feel more anxious, which is a stressed emotional state, and that the central feature of burnout is emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, and importantly, the respondents in this study were all full-time working adults, indicating that shy employees appear to be more susceptible to burnout than less-shy workers. This confirms that managers need to be concerned about this. Fortunately, the findings suggest how managers can resolve this situation because emotional exhaustion was significantly and negatively related to coworker support, and coworker support was a moderator for improving subjective career success among shy employees. That is, to the extent that managers can facilitate coworker support in their organizations, they should be able to reduce burnout and also increase their shy employees’ feelings of career success.

Shyness and Subjective Career Success [TOP]

The results supported the hypothesis that the shyer the employees are, the less subjective career success they have. Also, the t-test result revealed a clear difference in subjective career success. That is, the shy employees scored significantly lower on this measure than the non-shy employees. These findings seem to coalesce the few isolated studies that showed poor job performance among shy employees (Moscoso & Salgado, 2004), that shy people have doubts about their chosen job path (Cheek & Melchior, 1990), and that shyness might negatively affect career development (Phillips & Bruch, 1988).

Hence, the findings in this study, regarding organizational socialization as a beneficial moderator between shyness and subjective career success, offer managers meaningful ways to help shy employees. Specifically, companies can help shy employees by giving them good job training, helping them understand the organization and how it functions, facilitating coworker support, and offering good opportunities for salary increases, promotions, and/or other company benefits. That is, by instituting a good program of organizational socialization in their companies, managers can help shy employees to overcome their relative deficits in job performance and to achieve equitable perceptions of their career success.

Organizational Socialization as a Moderator Between Shyness and Career Success [TOP]

Prior research found that shy people have problems not only with social relationships, but also with job performance and career progress. Yet, organizational socialization is supposed to help employees achieve better task performance, understanding of their work environments, collegial acceptance, and future prospects in the workplace. This suggested that organizational socialization should have the potential both to improve those work-related factors and moderate the relationship between employee shyness and the shy employees’ perceptions of their future career success.

The present study found precisely this, namely, all four facets of organizational socialization (i.e., training, understanding the organization, coworker support, and future prospects at work) yielded significantly greater levels of subjective career success when those facets of organizational socialization were at higher levels.

Taking each facet individually, shy employees, as compared to non-shy employees evidently perceived higher levels of Training as a way to achieve career success, and to a significant extent. That is, if shy employees worry that their performance is not up to standard, the superior training they receive apparently alleviates those worries, which gives them a much more positive sense of their potential career success.

For Understanding, when shy employees gain a greater understanding of how the organization in which they work operates, this seems to alleviate their worry that they might make mistakes such that they are more confident that they can succeed, which also gives them a more positive view of their chances for career success.

For Coworker Support, the correlations and mean differences showed significant results, which confirmed that shy people are at a disadvantage in the amount of support they receive from coworkers. Fortunately, the interaction between Shyness and Coworker Support demonstrated that shy people benefit significantly in terms of perceived career success when they receive higher levels of coworker support. Based on these results, the implications for management, e.g., supervisors and managers, seem clear, that is, managers may help shy employees with their (the employees’) feelings about work when managers encourage and find ways to increase collegiality. For example, this could be accomplished by matching shy workers with friendly and helpful mentors, or by assigning shy employees to successful work teams. According to the current findings, the overall result of having good coworker support in an organization would be to help shy employees achieve levels of perceived success that are equal to those of other employees.

Regarding Future Prospects, the results of all the statistical analyses were consistent. For employees, shyness had a strong negative correlation with Future Prospects, which was confirmed in the mean scores that showed a significant deficit for shy compared to non-shy employees; and Future Prospects was a powerful predictor of Subjective Career Success. Fortunately, as with the other socialization facets, the interaction between Shyness and Future Prospects revealed that shy employees had a significant increase in the anticipation of career success when they believe there are opportunities for them to advance in the organizations in which they work. Implications for management are again clear. When the managers of an organization make it known to their shy employees that they, too, can earn higher salaries and attain professional advancements, even shy employees gain a positive outlook regarding their work.

Conclusions and Future Research [TOP]

Based on the literature, which indicated that shy employees often have difficulty adapting to interpersonal and professional demands in the workplace, this was the first study to investigate the moderating role of organizational socialization on the relationship between shyness and subjective career success for employees. Specifically, the results provide evidence that organizational socialization can play an important, positive role in helping shy employees at work. That is, relative to non-shy people, shy employees start work with lower levels of self-confidence, which could reduce their work effectiveness, have higher levels of emotional exhaustion, and anticipate lower levels of career success. But the results of the present study demonstrated that each of the four organizational socialization domains, namely, Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, and Future Prospects, had a moderating effect that brought the shy employees up to the same or similar levels of Subjective Career Success as the non-shy employees.

These results should be seen as encouraging for shy people in the workplace, and they also provide clear implications for management. Managers who institute into their companies the four components of an organizational socialization program would be playing an active role in helping shy employees better assimilate into their companies, which should give those employees a more positive outlook on their work and on their futures in the companies and in their careers. And having such a positive outlook should make those employees more effective workers, which can help organizations achieve their missions and objectives.

Regarding future research in this area, more insight may be gained about shy employees by (a) studying additional job-related variables that might influence shy workers, such as mentoring, team building, and informal socializing, (b) doing more research that assesses organizational socialization as a moderator between shyness and other workplace variables, such as organizational commitment and work engagement, and (c) conducting studies of this research in several countries for cross-cultural comparisons.

Contents

Contents This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (