Introduction [TOP]

Recent statistics on the prevalence of ASC in the UK child population highlights that a ratio 1:100 children are diagnosed (Baird et al. 2006; Baron-Cohen et al., 2009) with the condition. Some theories suggest that the traditional Triad of Impairment is to be looked at focusing on differences in their social communication, social interactions and in their stereo-typed patterns of behaviors, which are unusually strong and narrow and which often inhibit access to learning (WHO, 1993). However, more recent diagnostic criteria have clustered together the domain of social communication and interactions as one category and the rigid/negative stereotypic patterns of behaviors as the other (Colombi, Kim, Schreider, & Lord, 2012; Wing, Gould, & Gillberg, 2011). When looking at how these young people learn, it is important to highlight how every child acquires and masters a repertoire of skills in a unique and individual way. Further, if we are to address this uniqueness throughout their educational lifespan, it is important to understand how this can be better achieved through addressing questions on the “how” and the “what” – which approaches and interventions, “when” best to adopt them and “who” should be involved.

Some research suggests that not one single approach can be consistently applied successfully for the education with young people with ASC (White, Smith, Smith, & Stodden, 2012). A large body of literature supports the application of Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) (Scott & Bennett, 2012). These approaches have also attracted criticism for the way that they are both time and resources intensive, as well as questioning their social validity, because of the implied dependency on adult support rather than working towards independence and autonomy (Yeaton, 1982). Wolf (1978) suggests three different levels of social validity as follow: (1) the social significance of goals, (2) the social appropriateness of procedures, and (3) the social importance of effects.

TEACCH based approaches are also often adopted in the presentation of life and educational skills (Mesibov & Shea, 2010; Mesibov, Shea, & McCaskill, 2012; Mesibov, Shea, & Schopler, 2004). Critics of the approach have focused on a lack of evidence-based research, though a number of articles and case studies are now in the literature notably from Europe and Japan. Notomi (2001) reports on five case studies using TEACCH interventions in Japan. We should note that these were not controlled trials and were lacking a standard objective assessment tool which perhaps led to a vague outcome and reliance on specific ways of responding to the environment which has subsequently led to a lack of precision in the way progress and change in the person was actually measured. Literature on TEACCH has been however described as ‘very positive’ but not ‘remarkable’ (Jordan, 2002).

This paper illustrates the work carried out with a young person with ASC named TJ and looks at specific key questions that provide a starting point in understanding from a person-centered approach as opposed to - as often happens - starting from a specific methodology or approach per se. A bottom-up approach is here adopted which looks and evaluates the needs of the young person prior to devising, implementing, monitoring and evaluating a specific individualized positive approach. That is opposed to adopting a top down approach, where existing methodologies are adapted to the person.

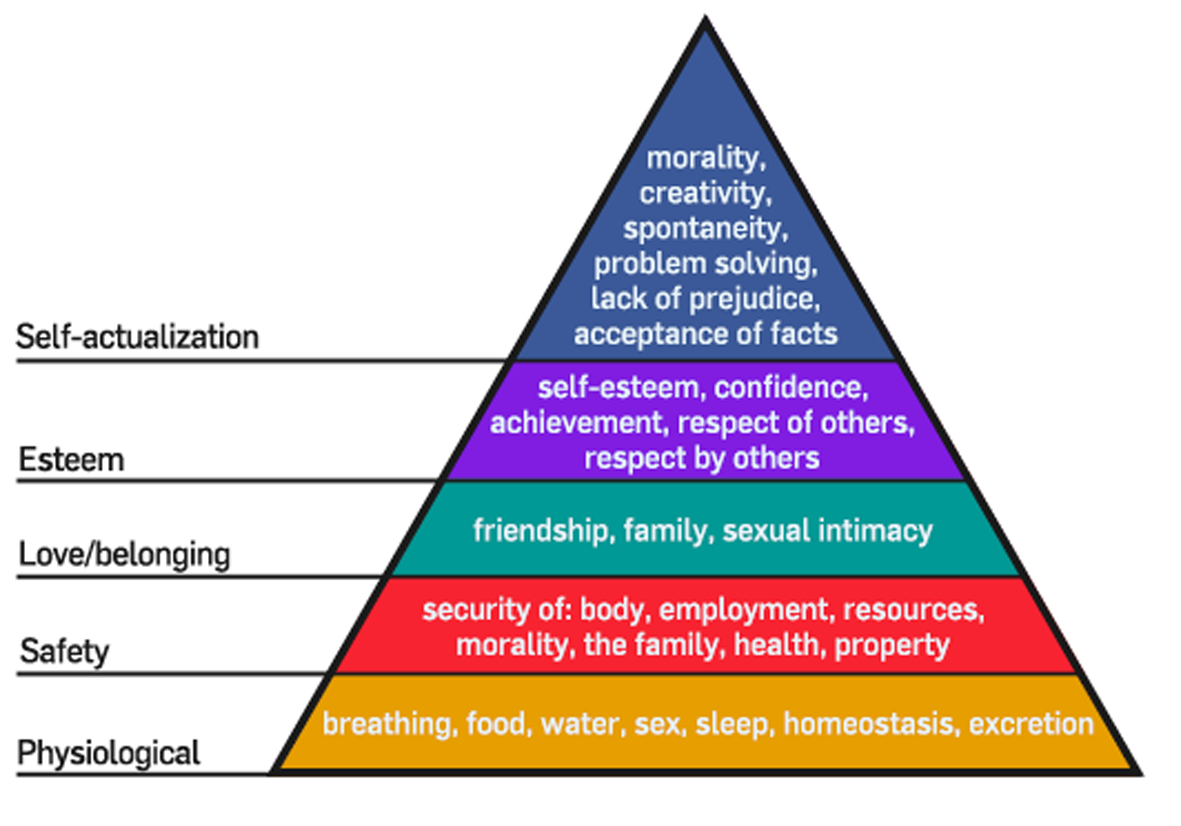

Figure 1 (see below) illustrates a framework adapted from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which can be used to address all different human needs and characteristics, skills and areas for development of each unique young person. This will also be used as a reference point to address the design of interventions and programs.

Within this context we can move to understand how we have addressed barriers to learning, what has been used to achieved it, when has it been adopted, and by whom.

How - Individual needs are to be addressed by individualized programs which are person-centered and tailored to the needs of each individual. They are designed with the aim to empower and highlight their strengths and positively address, challenge and re-model their weaknesses.

What – Functionally related skills, relevant to the needs of each individual, which need to be identified in order to address all areas of development. These functional related skills need to be gradually nurtured as part of a comprehensive program which is related to the areas of interests of each individual. They aim to substitute the functions of those inappropriate/maladaptive patterns of behaviors and support the individual in learning new alternative responses.

When –This is an ongoing process that needs to be consistently and regularly monitored according to the needs of the changing individual, as they grow and develop as any other human being. They need to be risk assessed and ideally with the full young person’s involvement and participation.

Who - Participation of the individual, their empowerment, their collaboration and input alongside communication with all professionals, carers and educators involved (sharing, reflecting and networking) should be also part of this program. The emphasis is on independence, rather than dependency, so that support staff can rotate but provide at the same time that all important consistency and continuity.

Figure 1

Adaptation from Maslow (1943). A theory of human motivation.

Throughout five years of secondary special educational provision, the young person will have to cope with a number of changes and transitions which are typical of any secondary curriculum. Changes and transitions can be a challenge for young people with ASC (TIN, 2009) therefore these key times will also be discussed showing how preparation, planning, solution-focus and choices can make a difference in their life at school and in the community.

The aim of this paper is to present results from a holistic application and evaluation of a repertoire of intervention programs adopted for a single-subject case study throughout their educational provision from beginning of secondary education to post-16 provision.

Method [TOP]

A mixed method approach was adopted for this single-subject case study. Data was collected over a period of 6 yrs at three age points:

-

11 yrs old (upon admission within the first 6 mths)

-

15 yrs old (upon transition to post 16 provision)

-

18 yrs old (upon entering adulthood)

For confidentiality purposes and in adherence to British Psychological Society (BPS) ethical guidelines all names have been replaced by pseudonyms. Data was collected to measure progress in the following areas:

Results and Discussion [TOP]

The results are presented and discussed via, in the first instance, a summary of interventions and programs adopted under each section and illustrated in Table 1 (see below); secondly by addressing three different areas of progress.

Table 1

Summary of Interventions Techniques

How - TJ was admitted to a special educational school at 11 yrs of age. Up to transfer to secondary special educational provision TJ experienced a very chequered educational life where various placements were sought as a result of a number of difficulties, including many incidents of challenging behavior. High levels of adult support had been reported often resulting in 2-3 staff supporting at any one time. Upon admission TJ was supported with two adults at all times. A repertoire of assessments were administered both upon admission and throughout the first six months, including the Adolescent and Adult Psycho Educational profile (AAPEP) which enable us to ascertain level of functioning, areas for further development, and areas of strength in six different functional areas including vocational skills, independent functioning, self-occupancy skills, vocational and interpersonal behaviors and functional communication.

What – The initial concern was to ensure that TJ’s experience returning to school was going to be a positive one. This included looking at ways in which TJ was gradually re-integrated in a small group of peers, enjoying and accessing a range of subject curriculum activities, through both individual and small group work. Key skills which were identified as significant for TJ were:

-

Communication – especially the ability to understand instructions (receptive language) as well as expressing specific needs and wants

-

Self-regulation – especially the ability to regulate unpleasant and/or negative emotions such as anger and frustration

-

Tolerance and coping skills – especially the ability to cope when things did not go the way TJ wanted

-

Stable relationships – especially the ability to build consistent and positive links with a number of key staff initially, to then subsequently rotate and increase the number of staff supporting him.

When – The work which was undertaken was done over a long period of time. Consistency, perseverance, continuity, as well as monitoring, evaluation and reflective revision remain key elements of implementation and success. As the young person develops and grows, changes occur and therefore it is also important to evaluate and assess situations as they occur.

Who – When TJ started school at secondary provision, there was very little trust with staff. Only a handful of staff was able to get positive results and feedback, or get a response from TJ at all. However, as TJ has grown more comfortable and confident so has the ability to cope, tolerate and accept the presence as well as the demands of other adults. This has made it possible not only to expand the range of activities accessed but also the range of adults involved in TJ’s care. It will be significant as TJ enters and continues the pathway to adulthood that a range of professionals continue to be engaged and that open and significant information is shared between key services with full involvement of TJ and TJ’s family; to facilitate a significant and meaningful transition which will support TJ in the next stage of life.

The paper will now present and discuss areas of progress as follow:

1. Positive Behavior Support Management

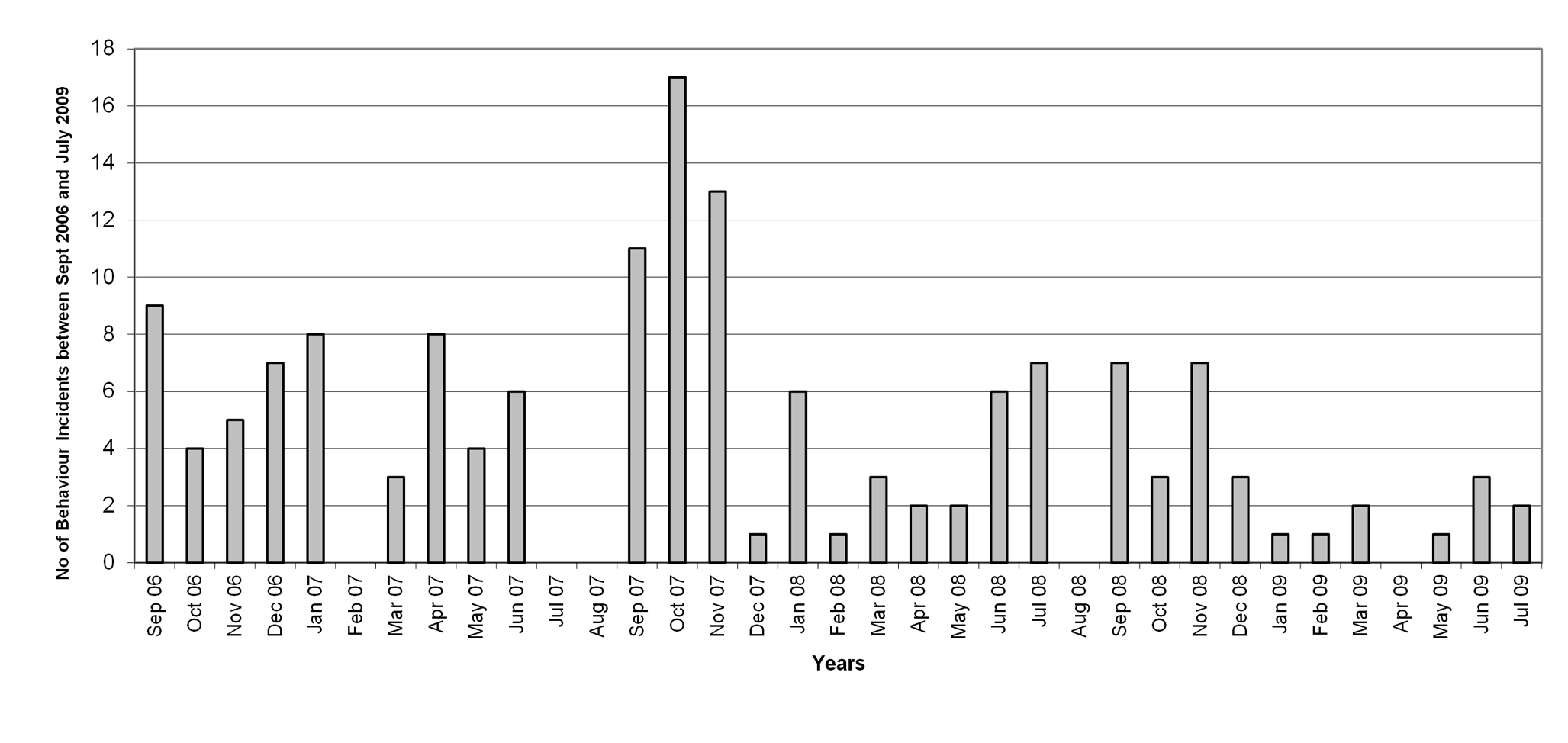

The frequency of behavioral incidents was chartered over a period between September 2006 and the end of the academic year 2009 (31st July 2009). As demonstrated (see Figure 2) the number of behavioral incidents per month was seen to decrease over time. As a result of the application of positive behavior support and low-arousal approaches, combined with investing time to build trusting relationships based on mutual respect, clear expectations and negotiations, TJ was slowly able to explore different activities without engaging in maladaptive/challenging behaviors.

Incidents were also recorded between 2nd January 2011 and 15th July 2013 demonstrating a decrease of frequency between 2011 and 2012 from 10 incidents and 2 incidents respectively. When comparing the overall decrease of previous years we can observe a typical increase between 2012 and 2013 (extinction burst) which might be explained by a significant change in the transition of TJ to KS5 – sixth form – where TJ had to re-adapt to a new curriculum, new staff and peers in a relatively short period of time.

2. Access to Community Based Activities and Extra Curricula

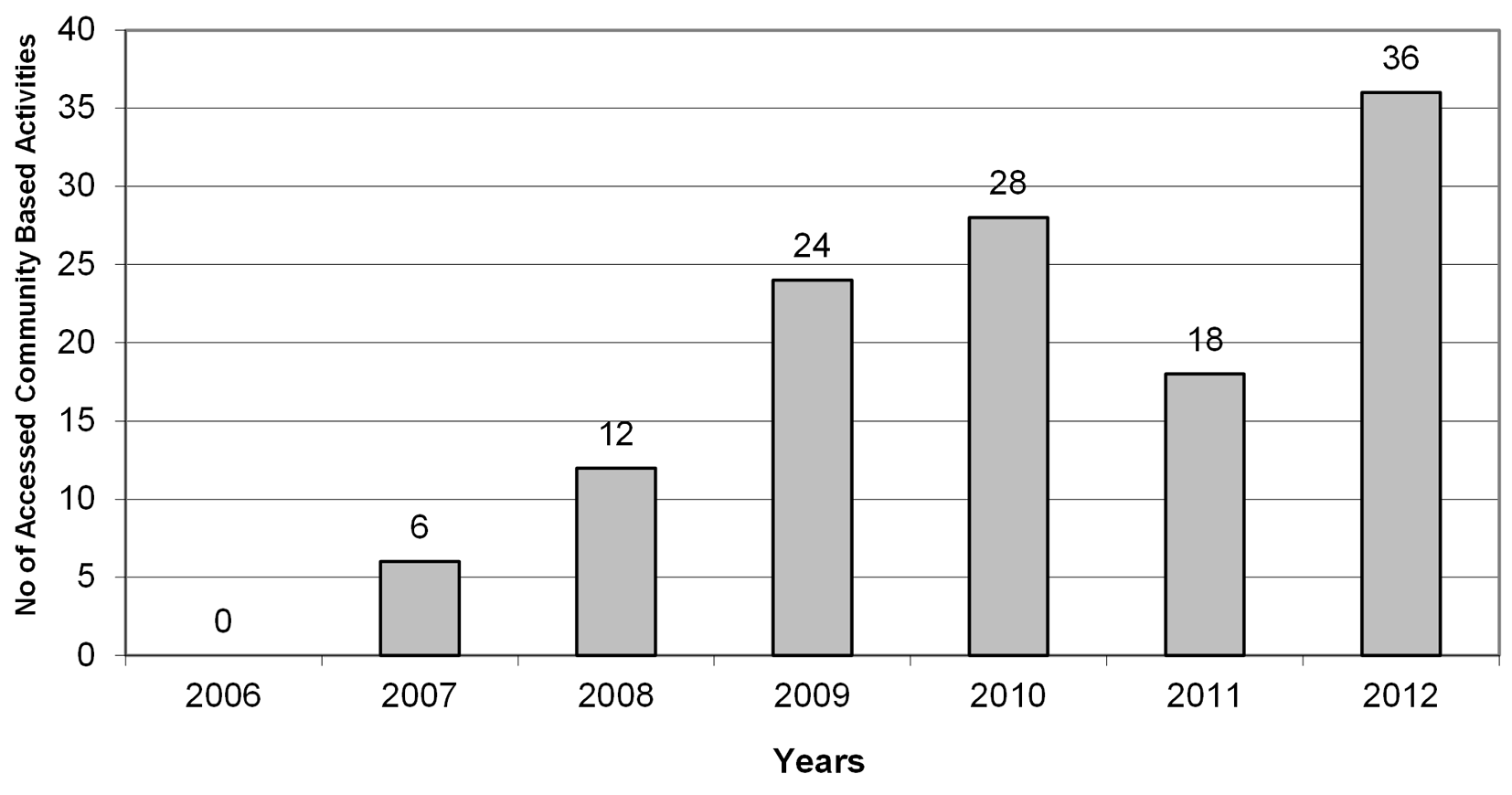

Quantitative progress was demonstrated through the years with TJ’s ability to access a greater number of community-based activities (see Figure 3) as well as the qualitative progress reached when analysing the breath of these activities. As a result of a positive approach and decrease in incidents of challenging behaviors, TJ was able to access and participate to a greater number of community based activities including trips going fishing, trips to the local shops and library, access to college and extra curricula (enhanced) courses such as the ability to successfully complete a food handling qualification.

3. Level of Staff Support

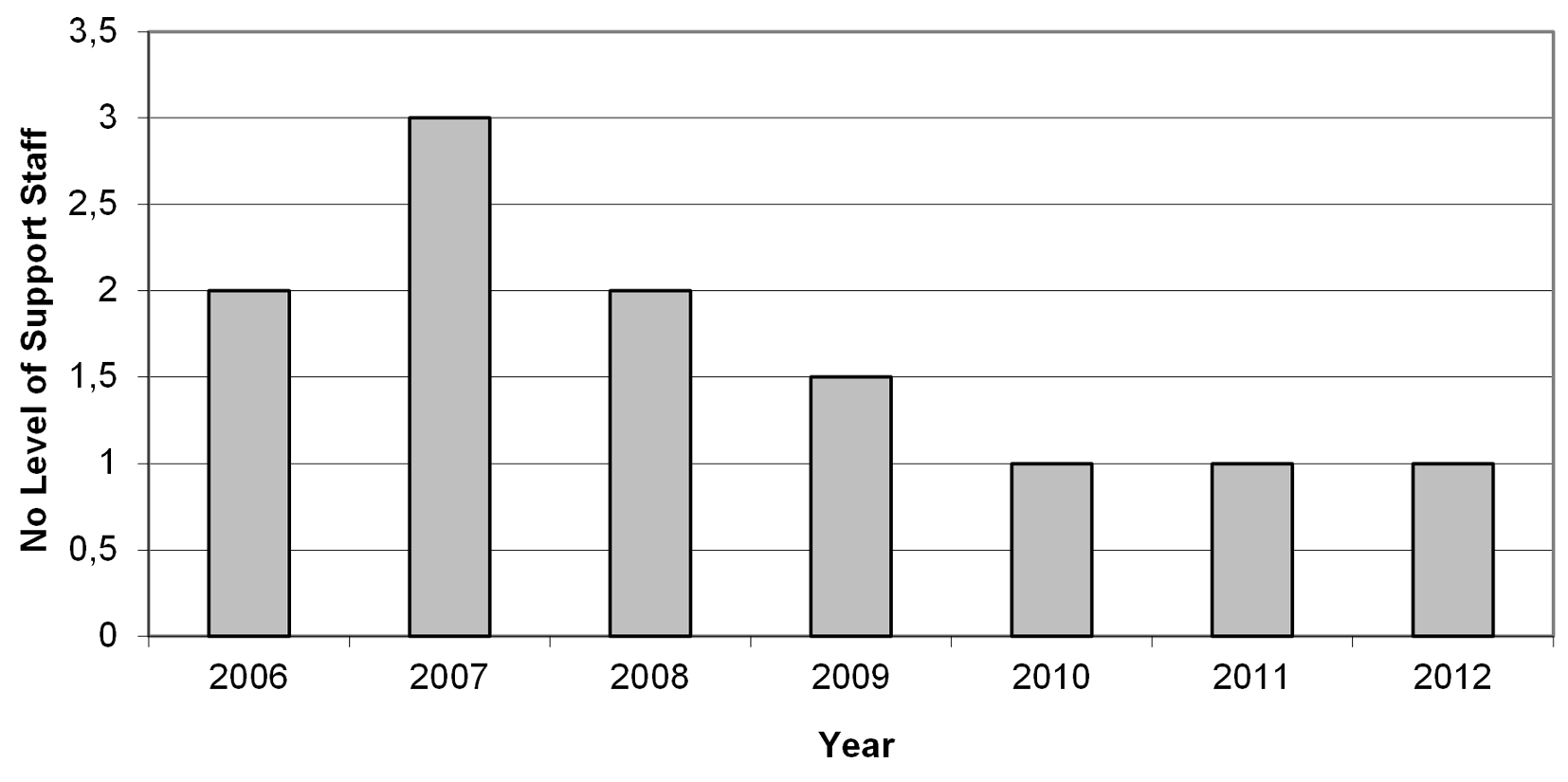

This is an area which demonstrates that if appropriate, individualized, sensitive and carefully monitored programs are in place, which address the presenting issues, progress can be demonstrated. Whilst during highly challenging situations the safe management of incidents has required a high staff ratio, progress was demonstrated by an overall reduction of level of adult support over time (see Figure 4), with increased ability for TJ to make choices, independence in accessing a range of school based activities, tolerance and coping strategies. This in turn has allowed TJ to be more engaged in his participation in school community. TJ’s confidence as a consequence has also increased, giving the opportunity to try new tasks and learn new skills, with less risk of confusion and a greater sense of control. Sense of control and choices are contributing factors when looking at Maslow’s areas of self-esteem and self-actualization. TJ has demonstrated a greater sense of control over his life which in turn has enabled him to increase his sense of achievement and confidence in what he was doing: a process of positive reinforcement, which has occurred by the intrinsic enjoyment and motivation of the activity chosen.

Conclusions [TOP]

The paper presented and discussed results from a mixed method single-subject design where a person-centered and holistic approach was adopted throughout the educational life of a young person with ASC. Human needs, characteristics, skills and vulnerabilities are to be assessed on an individual basis as they are unique to each individual. By trying to ‘fit’ a model for all we may not necessarily capture or indeed understand individual needs for each young person. Programs which are person-centered and tailored made will facilitate a flexible and yet consistent way of working in supporting young people on the spectrum. Looking at identifying strengths and interests of the young person is a key element, alongside facilitating them. This process in turn will give the young person a sense of control and a sense of choice. For behavioral changes and optimal performance to occur key psychological factors that need to be considered are a) sense of autonomy, b) intrinsic motivation and c) relatedness. These can influence and determine potential changes in behavioral patterns and performance (Ryan & Deci, 2000). As intrinsic motivation is adopted to reinforce desirable behavioral responses, the young person reaches a better quality of social engagement and general well-being. This paper has demonstrated that with the application of planned programs, progress can be demonstrated not only by a reduction of maladaptive and challenging behaviors but also by an increased quality of access and involvement in the activities offered. This can also lead to a subsequent reduction of adult support. Research could further explore how to maintain this gradual and consistent level of progress and how changes in individual needs and aspirations could be further assessed and monitored with full participation of the young person.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (